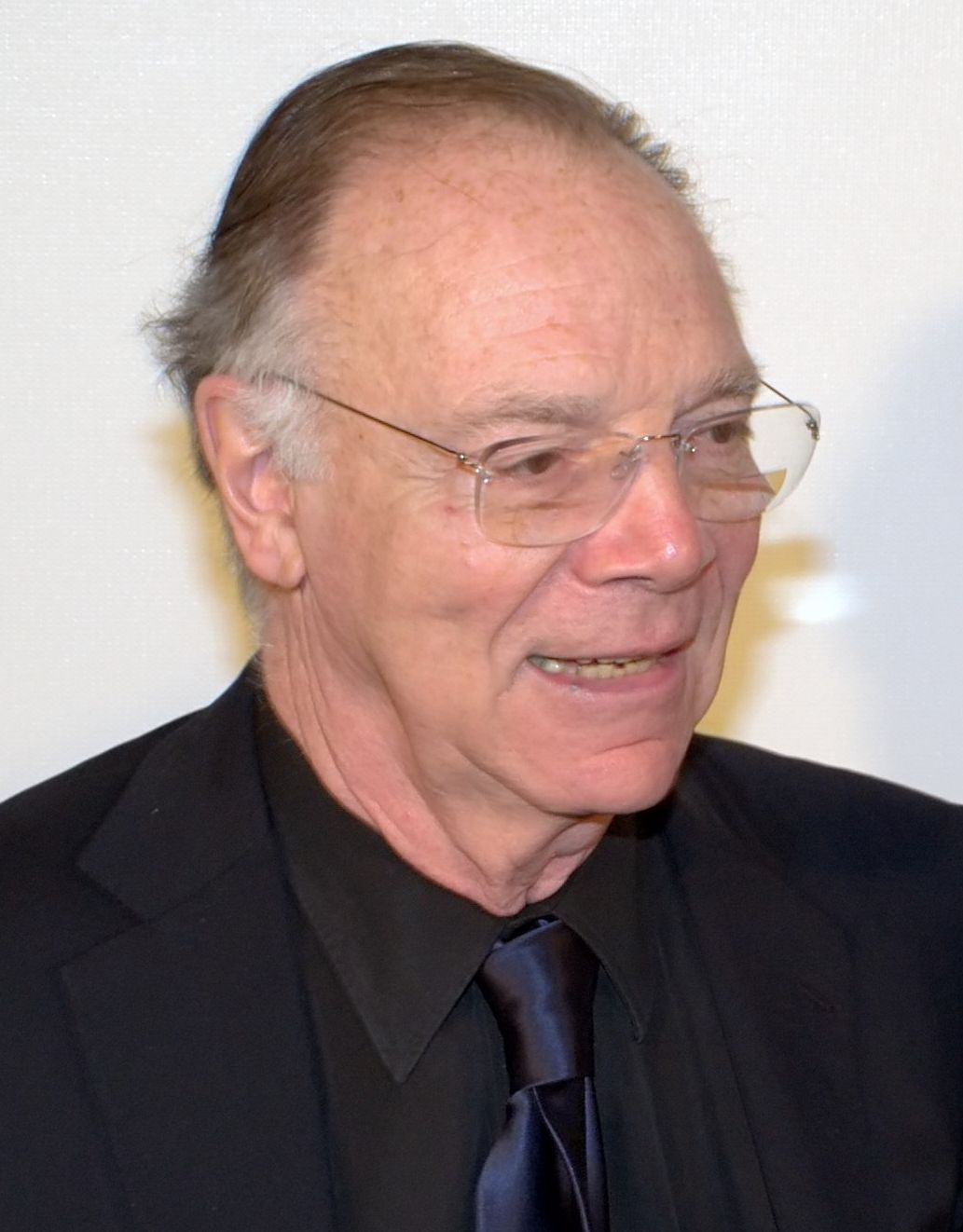

From shoe-leather reporter to Mob movie screenwriter, Nick Pileggi remembers it well

Pileggi’s reporting led to screenplays for the classic films Goodfellas and Casino

Author and screenwriter Nicholas Pileggi is enjoying a couple of major career milestones this year. Two groundbreaking Mob movies he wrote with director Martin Scorsese — Goodfellas and Casino — are undergoing anniversaries.

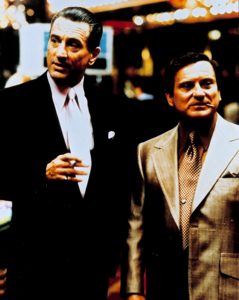

Goodfellas, starring Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci and Lorraine Bracco, and featuring Ray Liotta as Irish-Italian gangster Henry Hill, premiered 30 years ago in September. The movie is based on Pileggi’s 1985 book Wiseguy about Hill’s criminal ascent from juvenile gofer for neighborhood Mafiosi in Brooklyn (“As far back as I can remember, I always wanted to be a gangster”) to his turncoat adult life as a protected government witness.

Casino, the Las Vegas Mob movie based on Pileggi’s nonfiction book of the same title, is celebrating its 25th anniversary. Starring De Niro, Pesci and Sharon Stone, Casino is a fictionalized account of Las Vegas casino executive Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal’s rocky relationship with his wife, Geri (De Niro and Stone), and her romance with the Pesci character, based on Tony Spilotro, the Chicago Outfit’s overseer in Southern Nevada during the 1970s and early ’80s.

In a recent telephone interview, Pileggi, who celebrated his 87th birthday in February, recalled his early days as a New York City crime reporter, the times he spent in Las Vegas with his wife, the writer Nora Ephron, and the years working with Scorsese on scripts for the duo’s now-classic gangster movies.

Pileggi stumbled into journalism, having set out at Long Island University in the class of 1955 to become an English teacher and maybe a novelist like Ernest Hemingway. He read famous authors — James Joyce, Aldous Huxley — and typed out published books word for word to learn the tricks that make writers successful — the pacing, the tone, etc.

“You get into the rhythm,” he said.

Needing a job, he followed a friend’s suggestion and went for an interview with the AP, thinking it was the Atlantic and Pacific grocery store chain, but instead was the Associated Press wire service. He was hired.

“You couldn’t do that today,” he said, noting that candidates for journalism jobs these days often need a degree from a prestigious college program.

On the job, he covered labor leader Jimmy Hoffa, New Jersey mobster Anthony “Tony Pro” Provenzano and others, creating a card file on underworld figures.

“My timing was absolutely perfect,” he said of his start in journalism.

Pileggi even labored in the press building called “the shack,” across from what was then police headquarters on block-long Centre Market Place in Lower Manhattan, where other New York journalists, including the legendary tabloid photographer Weegee, worked. Pileggi became acquainted with Weegee (real name Authur Fellig), but by then the famed street photographer was near the end of his career.

Moving into long-form writing at New York magazine, Pileggi worked with some of the best-known reporters then practicing the New Journalism, including Tom Wolfe, Jimmy Breslin, Pete Hamill and Gloria Steinem.

The magazine’s editor, Clay Felker, pulled Pileggi in by saying to the wire service reporter, who wrote under tight deadlines, “What the hell are you doing at the AP? I’ll match your salary.”

Magazine work led to an interview with gangster Henry Hill, who was seeking a writer to tell his story. Mob authors such as Peter Maas also were considered, but Pileggi, who had built that card file, knew a lot of the same people as Hill, even down to their nicknames.

“Henry and I hit it off,” Pileggi said.

After the success of Goodfellas, Scorsese approached Pileggi, looking for something new. “What are you doing next?” Scorsese asked him.

As it happened, Pileggi had seen a news story about the illegal skimming of casino revenue at the Stardust hotel-casino on the Las Vegas Strip and got in touch with Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal, the Chicago bookmaker who oversaw the skim for mobsters in the Midwest.

But Rosenthal said no, even with the possibility of some money on the table.

Pileggi then located Frank Cullotta, a Spilotro lieutenant in Las Vegas who had testified against his associates and, like Hill, had entered the Witness Protection Program. Cullotta had led the so-called Hole in the Wall Gang, which burglarized businesses and homes in Southern Nevada by punching holes in the walls and ceilings. The crew was arrested in 1981 attempting to break into what was then Bertha’s Gifts and Home Furnishings on East Sahara Avenue. The store also sold jewelry.

With Rosenthal reluctant to talk and Spilotro murdered by then, Cullotta would be the focus of Pileggi’s new book. Cullotta opened up about Spilotro, including the Chicago mobster’s romance in Las Vegas with Rosenthal’s wife, a former showgirl at the Tropicana, who also was dead by the time Pileggi began digging into the story.

Pileggi said of Cullotta, “He was fabulous.”

After Scorsese green-lighted the project, word got out that a Las Vegas Mob movie was in the works, with De Niro slated to portray the Rosenthal character.

“The phone rings. It’s Rosenthal,” Pileggi said. “He said, ‘I heard on the radio that De Niro is supposed to play my part. Could I talk to De Niro?’”

Soon after, De Niro was on a plane to Boca Raton, Florida, just north of Miami, where Rosenthal was living, to meet with the sports handicapper and former Las Vegas casino operator.

“They hit it off right away,” Pileggi said.

In no time, Rosenthal’s home filled with people wanting to meet De Niro, including Rosenthal’s daughter and, by 5 p.m., even Rosenthal’s pool guy.

“He told everybody De Niro was there,” Pileggi said.

From that point on, “Lefty opened up to me,” Pileggi said. Others in Las Vegas also helped with the project, including Oscar Goodman, a Mob lawyer and future Las Vegas mayor, and casino owner Steve Wynn. Pileggi and his wife, the film director and screenwriter Nora Ephron (Sleepless in Seattle, When Harry Met Sally), hung out at Wynn’s Golden Nugget on Fremont Street downtown, playing craps and enjoying their time in Las Vegas. Ephron, who died in 2012, also had liked shooting craps with her husband at the Sands on the Strip, which since has been torn down and replaced by the much larger Venetian hotel-casino. The Stardust also has been demolished. Resorts World Las Vegas is going up at the same location.

“We all had a good time,” Pileggi said of those earlier days in Las Vegas.

With Rosenthal on board, the focus for the book and movie shifted from Cullotta to the love triangle involving the Rosenthals and Spilotro, and to the skimming operation. The names were changed for the movie, but many of the details, including the still unsolved bombing of Rosenthal’s car in the early 1980s outside what then was a Tony Roma’s restaurant on East Sahara Avenue, mirror real-life experiences. Rosenthal moved away from Las Vegas not long after the bombing and died in Florida in 2008.

To this day, Pileggi speaks fondly of his experiences in Las Vegas and is grateful to those who assisted in pulling the Casino story together.

“Oscar was unbelievably helpful,” he said of Goodman, who is on The Mob Museum board of directors. Goodman and Cullotta also had minor roles in the movie, Goodman playing himself and Cullotta playing a hitman.

Wynn also gave freely of this time, Pileggi said, adding that he got along well with Wynn. Pileggi and Ephron were present when the casino operator accidentally punched a hole in an original Picasso painting in his office at the Wynn hotel-casinop. Years later, Wynn stepped down as chairman and chief executive of Wynn Resorts amid sexual misconduct allegations that he has denied.

Pileggi liked Rosenthal but found him to be complicated, on one hand “a pain in the ass” and on the other “a charming guy.”

“He was a loner,” Pileggi said of the longtime bookie. “He only rooted for the odds. He couldn’t root for anybody. It kept him distant.”

Now with Goodfellas and Casino being celebrated during their anniversary years, Pileggi is continuing to work on new projects. At heart, he is still a shoe-leather reporter digging out stories, as he was in New York City while working for the Associated Press — the AP.

“I’d go back in a minute if they would take me,” he said.

Larry Henry is a veteran print and broadcast journalist. He served as press secretary for Nevada Governor Bob Miller, and was political editor at the Las Vegas Sun and managing editor at KFSM-TV, the CBS affiliate in Northwest Arkansas. Henry taught journalism at Haas Hall Academy in Bentonville, Arkansas, and now is the headmaster at the school’s campus in Rogers, Arkansas.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org