Go ahead, tough guy. Come on in. We dare you.

If this building could talk, there’s no telling what secrets it would reveal.

From the Kefauver hearings to trials to information shared as federal agents passed each other in the hallways, compelling history happened within this building, now home to The Mob Museum.

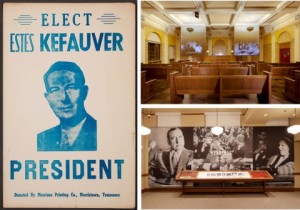

Las Vegas casino owners and managers with ties to notorious Mob bosses arrived in our second-floor courtroom on November 15, 1950, to answer questions about the Mob from members of the U.S. Senate’s Special Committee to Investigate Crime in Interstate Commerce. Well-known Las Vegas residents who testified included Moe Sedway, manager of the Flamingo Hotel, and Wilbur Clark, front man for the Desert Inn.

In recent years, Las Vegas has become better known for demolishing old buildings than for preserving them. Even so, it has saved a few of its historic structures.

One of the most important examples of Las Vegas letting sleeping dogs lie is our building, the storied neoclassical building in which The Mob Museum resides. Even the nation’s “urban renewal” capital knew better than to try to knock this baby down. Maybe they were afraid of what they might find lurking in the foundation?

This building at 300 Stewart Avenue in downtown Las Vegas opened in 1933 as the U.S. Post Office and Courthouse. Las Vegas is still a young city — it got its start in 1905 — so by local standards it’s a very old building, so much so that it’s listed on the Nevada and National Register of Historic Places.

The timing of the building’s construction is significant. Federal officials started scouting sites for their local presence in 1929 — not long after plans were announced for the construction of Hoover Dam, thirty miles south of Las Vegas. They knew this town was going to grow and would need a federal building. Perhaps they also followed all kinds of murky money trails that led out this way, and figured they’d best set up shop.

Construction began in 1931, and the building was dedicated on November 27, 1933. From the beginning, it was best known as a post office. The courthouse was not heavily used in the early years, as Nevada’s only federal judge was more than 400 miles away in the state capital of Carson City. So judges from Los Angeles and San Francisco traveled here twice a year to hear cases. That practice persisted until in 1945, when Las Vegas got its first full-time appointed judge.

It wasn’t too long before the building gained national attention. The courthouse was the setting for one of the famed Kefauver Committee hearings. On November 15, 1950, the U.S. Senate Special Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce, led by Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver, heard testimony in the courtroom on the second floor (which has since been restored to reflect what it looked like at the time of the hearing). The Kefauver hearings, held in fourteen different cities, ultimately exposed much of the seedy underbelly of organized crime across America, particularly in Las Vegas. A lot of pretty unsavory stuff started coming out in the wash. Not all of it, pal … but plenty.

In 2002, the feds sold the building to the City of Las Vegas for $1, with the stipulation that it be preserved and used as a cultural center. Preferably, a museum. Then-Mayor Oscar Goodman, who had represented mobsters as a defense attorney, proposed a museum that would explore the complicated history of the Mob, and its mostly hidden role in society. With the support of federal, state and local grants, the building was renovated. The nation’s leading museum designers were hired to create an institution telling the true story of organized crime and law enforcement in America. We think they did a pretty good job. And if you know what’s good for you, you’ll think so, too. Maybe even tell your friends, eh?

The Mob Museum opened on February 14, 2012, and has played an important role in the revival of downtown Las Vegas. After the renovations that restored many of the building’s historical features, it earned LEED Silver certification. In 2022, a mural honoring the city’s history was completed along the Museum’s retaining wall. Done by respected local artist Miguel Hernandez, and funded in part by a grant from the Nevada Humanities, this 300-foot-long mural charts the city’s development from the 19th century through the 1970s.