DEA report: Drug overdoses top cause of death for Americans

Latin American, Chinese gangs keep pushing deadly fentanyl across the border

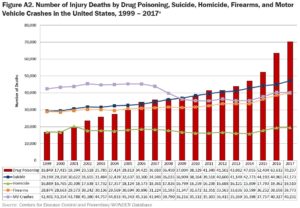

Drug poisoning was the chief cause of injury deaths among Americans from 2011 to 2017, more than the loss of life from firearms, car accidents, suicide or murder, while overdose deaths from illegal opioids and prescription opioids declined somewhat in 2018.

These lethal drugs include fentanyl and other illegal synthetic opioids trafficked by transnational organized crime groups from Mexico and China, heroin and methamphetamine sourced from Mexican drug cartels, and cocaine manufactured and distributed by Colombian gangs.

The most drug-involved deaths of Americans arise from people abusing domestic prescription pain relievers such as hydrocodone, oxycodone and other controlled opioid narcotics prescribed in the United States, which in 2018 amounted to 11 billion doses. More than 17,000 people died from prescription overdoses, about 47 per day, in 2017. More than 50 percent of people surveyed who admitted to misusing a prescription pain drug said they received the pills from a friend or relative for free.

New guidelines and crackdowns on prescriptions in all 50 states have reduced the amount of prescribed opioids in society, and the once serious rash of robberies of prescription opioids has greatly declined. But many opioid abusers unable to get them legally have turned to street gangs selling counterfeit prescription drugs secretly laced with fentanyl and heroin that contribute to overdose deaths.

That’s all according to the latest “National Drug Threat Assessment” by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. The 2019 report examines drug crimes and deaths in America based on the most recent reports, as of 2018, from federal, state, local and tribal law enforcement, intelligence and public health agencies and DEA field divisions in 22 American cities and the Caribbean.

The good news is that in 2018, deaths from drug overdoses overall fell by four percent, and deaths from prescription opioids dropped by 13 percent. Furthermore, seizures of deadly fentanyl sent to the United States from China sank by 57 percent from 2017 to 2018, a sign of declining availability likely a result of tighter rules and restrictions by Chinese officials on manufacturers of chemicals used to create synthetic opioids.

Directly responsible for the human carnage from drug overdoses are organized gangs from Mexico, Central and South America and China. Drug poisoning killed more than 70,000 Americans in 2017, which is steep when compared with the more than 47,000 deaths from suicide, 19,500 from homicide, 39,000 from firearms and 40,000 in auto crashes that year.

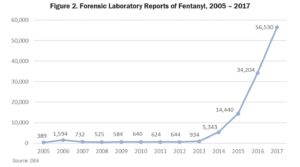

Despite the decline in deaths in 2018, America’s illegal fentanyl problem is still frightening. The 2017 figure for drug deaths was more than 10 percent higher than in 2016 — and close to double the 38,000 drug poisonings in 2010. As of 2017, the states with the highest rates of overdoses traced to fentanyl were West Virginia, Ohio, New Hampshire, Maryland and Massachusetts.

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid originally designed as a prescription drug to relieve severe pain. To abusers, fentanyl’s appeal is a “high” similar to heroin. But it is up to 100 times stronger than the pain reliever morphine and can cause death if ingested in amounts as tiny as two milligrams, like grains of salt on a fingertip. By comparison, it takes about 75 milligrams of heroin to trigger an overdose.

“Fentanyl remains the primary driver behind the ongoing opioid crisis, with fentanyl involved in more deaths than any other illicit drug,” according to the DEA report.

The chemically mixed opioid is smuggled into the United States from Mexico and China, sent directly across the Southwestern border or within packages by international postal mail or express shipping services. The pushers deliver it in powder form or press it into counterfeit pills meant to pass as prescription drugs.

More than ever, crime organizations are mixing fentanyl with heroin, cocaine and methamphetamines to provide ever-higher intoxications for customers, and a far higher risk of overdoses. The DEA said that from 2016 to 2017, laboratories that tested samples of drugs seized throughout the country found that instances of fentanyl mixed with heroin had climbed by 97 percent, fentanyl with cocaine up 74 percent, and mixtures with methamphetamine increased by 174 percent.

Mexican crime groups

“Mexican TCOs [transnational crime organizations] remain the greatest criminal drug threat to the United States,” the DEA states.

In Mexico, crime cartels control the flow of illegal drugs through the southern U.S. border, partnering with independent crime groups, American street gangs, prison gangs and Asian money laundering organizations. The Mexican TCOs smuggle and sell bulk quantities of heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, fentanyl and other drugs at wholesale prices to street gangs in U.S. cities that in turn peddle them to users at higher “retail” prices. The cartels typically deal with independent contractors in the U.S. who serve in specific roles in a supply chain to distribute drugs, receive payments and launder the proceeds, but the contractors know little about each other’s functions.

The DEA identifies six major TCOs in Mexico that smuggle drugs into the U.S.: the Sinaloa Cartel, Jalisco New Generation, the Beltran-Leyva Organization, the Juarez Cartel, Gulf Cartel and Los Zetas Cartel. While a huge number of drug-related murders occur in Mexico each year, little of that violence spills over into the United States, as cartels seek to avoid the attention of U.S. law enforcement, the DEA reports.

According to the agency, as has been the case for years, “the Sinaloa Cartel maintains the widest national influence [in the U.S.], with its most dominant positions along the West Coast, in the Midwest, and in the Northeast.” The next biggest narcotics trafficker to America is the Jalisco cartel. Beltran-Leyva, also seen throughout the United States, is heavily involved in heroin trafficking.

DEA field offices in San Diego, Atlanta and Los Angeles report that the Sinaloa and Jalisco are the top Mexican TCOs running drugs in their jurisdictions.

The Sinaloa, Jalisco, and Beltran-Leyva have recently expanded their presence in the Miami area, shipping in cocaine, methamphetamine, heroin, and fentanyl from Mexico. In New England, the Sinaloa dominates drug trafficking, selling on a wholesale basis heroin, fentanyl and cocaine to members of Dominican Republic-based TCOs that distribute the drugs to street gangs in the region. In Denver, the Sinaloa, Jalisco and Beltran-Levy control methamphetamine, cocaine and heroin sales.

Techniques used by Mexico-based gangs to sneak drugs (mostly synthetic opiates, cocaine, heroin, methamphetamine and marijuana) into the United States include tunnels beneath the Southwestern border, stashing supplies in commercial cargo trains and passenger buses and assigning individual “backpackers” or mules to walk supplies over land.

They also have drugs dropped across the border by air, using manned ultralight aircraft, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAS) and smaller drones. The cartels also deploy UAS crafts to monitor American law enforcement officers and find vulnerable areas to airdrop drugs.

Mexican gangs also captain sea vessels to transport drugs to locations off the coast of California, the state where more than 75 percent of all fentanyl seizures took place in the U.S. in 2018 (Arizona was next with 20 percent of the fentanyl confiscated).

As for laundering, or secretly hiding, the money earned from drug trafficking, Mexican TCOs favor moving mass amounts of U.S. currency. They deposit proceeds into U.S. banks, use money brokers and money service businesses to transfer money electronically to Mexico, park money in front and shell companies or simply purchase cars and other property.

One significant recent trend involves Mexican TCOs teaming with China-based money launderers to hide drug money. This developed after the Chinese government placed a cap on foreign exchange transactions to only $50,000 a year and $15,000 a year on withdrawals from credit and debit cards. Criminals in China seeking to exchange more than the government allows are increasingly interested in switching their money into U.S. dollars. These Asian criminals will buy Mexican pesos on the black market and then sell the pesos to Mexican TCOs for the U.S. dollars the TCOs obtained from trafficking drugs. Both sides thus succeed in laundering each other’s funds.

To complete the laundering process, the Chinese gangs resell the dollars at a profit to Chinese nationals living in the United States, usually in exchange for payments in Renminbi, the official Chinese currency used in mainland China.

This relatively new method of converting dirty money “has provided an outlet for Mexican TCO drug proceeds that is changing the landscape of money laundering within the United States,” the DEA states.

Colombian TCOs

Colombia, the South American nation that infamously reigned as the center of the cocaine trade in the 1980s and 1990s, remains the country of origin for most of the cocaine seized in the United States. Colombian TCOs collaborate with Mexican TCOs, providing multi-ton supplies of Colombian cocaine made from raw coca leaves, along with smaller caches of heroin that Mexican crime groups prepare for sale in America.

The Gulf Clan is the most significant crime organization trafficking cocaine out of Colombia. The clan is one of the country’s so-called Grupos Armados Organizados (GAO), or Armed Criminal Organizations that run the powdered drug trade with dissident members of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). The Gulf Clan routinely traffics tons of cocaine to Mexico, Ecuador and Venezuela, Panama and the Caribbean, using speedboats, fishing boats, near-submersible vessels and aircraft, ultimately bound for the massive U.S. market.

In America, Colombian TCOs use money launderers assigned to large cities, including Boston, Chicago, Miami and New York, to deposit drug profits into U.S. banks and then send the money to Colombia disguised as payments for nonexistent products and services.

Dominican TCOs

Another growing country of origin for illegal drug exports is the Dominican Republic. Dominican crime gangs dominate the mid-level distribution of cocaine and white powder heroin, using friends and family members of Dominican nationals and U.S. citizens in the Northeastern states and Florida. Most of the coke and heroin in the Dominican Republic is ferreted in small boats to Puerto Rico, a U.S. territory. The traffickers then arrange to fly the drugs on airlines to New York City and Florida. Other quantities arrive in the U.S. by boat or in packages via the U.S. Postal Service.

TCOs in tribal lands

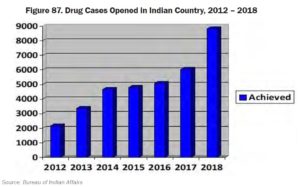

Crime gangs operating on Native American tribal enclaves also import illegal narcotics. Drug seizures in Indian Country have increased every year since 2011, and soared by 47 percent in 2018. The Tohono O’odham Nation Reservation, on a remote area in southern Arizona, has been a hotbed for Mexican drug smugglers. Canadian drug pushers cross the St. Lawrence River on the northern U.S. border from Ontario into the St. Regis Mohawk Reservation in New York State.

American gangs

Dozens of street gangs, prison gangs and outlaw motorcycle gangs, often overlooked on the American home front, continue to permeate the country. The gangs, on a local retail level, traffic heroin, synthetic opioids, methamphetamine, cocaine and marijuana from Latin America and China in addition to engaging in murder, robbery, extortion, burglary, sex trafficking and illegal firearms sales. Turf wars for dominance in the drug trade prompt members to turn to gun violence in residential neighborhoods.

Some of the gangs mentioned by the DEA include the Latin Kings, the California Mexican Mafia (prison group), MS-13, the 18th Street gang, the Nortenos, Surenos, Tango Blast, Aryan Brotherhood, the Bloods, the Rolling 90s Crips, and the Banditos and Pagans outlaw motorcycle gangs.

These crime hosts are found to operate in cities with DEA field offices: Atlanta, Chicago, Dallas, Denver, Detroit, El Paso, Houston, Los Angeles, Miami, Louisville, Boston, New Jersey, New Orleans, New York, Omaha, Philadelphia, Phoenix, San Diego, Seattle, St. Louis and Washington, D.C.

“As long as illicit drugs remain in high demand in America, street-level drug sales will continue to rank among the top criminal activities conducted by street gangs, who are lured by the prospect of huge financial gains,” the DEA states. “For the near future, street gangs will fight to remain major distributors of street-level drugs in the DEA [areas of responsibility], and assaults, intimidation, and homicide will be their means to this end.”

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org