Joe Gallo’s ‘Crazy’ celebrity status

Renegade Brooklyn mobster’s violent death capped unusual rise to fame

Though Joseph Gallo was only in his early 40s when he was gunned down, his status in American popular culture is permanently fixed in the way that oddball violent characters often are memorable.

A couple of books, a couple of movies, a Bob Dylan ballad — they all help define the blond, blue-eyed mobster who stood only 5 feet, 6 inches tall yet, after being snuffed out in New York City’s Little Italy, left behind a towering dark legacy.

Gallo’s shooting death capped a renegade existence, which, consistent with early 1970s counterculture New York, had celebrities swooning in his Nietzsche-quoting presence — or regretting the missed opportunity to enter his sinister, high-profile orbit.

“I wish I’d had the chance to talk to Joe Gallo before he died,” said writer Susan Sontag, described as the “voice of the city intelligentsia” in Tom Folsom’s 2009 book The Mad Ones: Crazy Joe and the Revolution at the Edge of the Underworld.

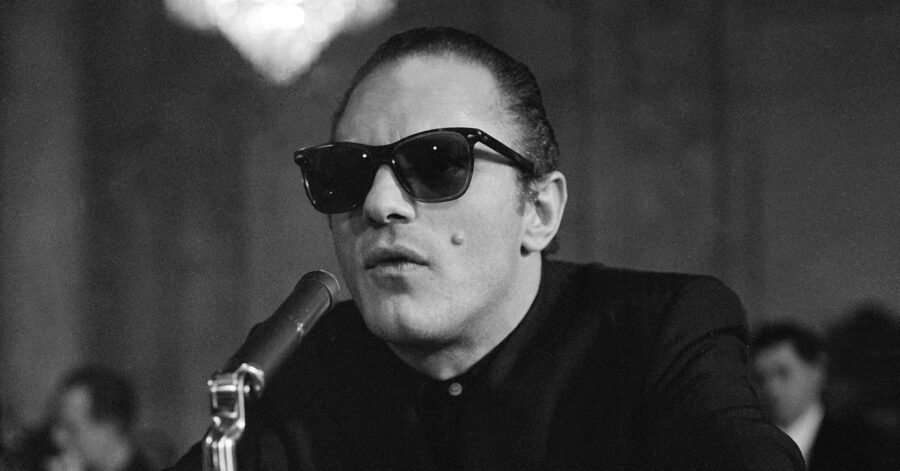

Called “Crazy Joe” because of his ruthlessness, the Brooklyn-born mobster once declared by a court psychiatrist to be paranoid-schizophrenic, was the subject of a 1963 Life magazine cover story, “Death Throes of the Gallo Mob,” and, ever the hipster, wore black Ray-Bans to a congressional hearing on organized crime.

In his early years, Gallo was said to have patterned his conduct after the creepy, cackling Richard Widmark character Tommy Udo in the 1947 film noir Kiss of Death, featuring one of the most horrifying scenes in crime-movie history: Udo shoving a gangster’s mom in a wheelchair, after binding her with an electrical cord, down a flight of stairs to her death.

In the 1950s and early ’60s, Gallo was a dangerous presence in the city. He was one of those believed to have assassinated Mafia boss Albert Anastasia, the Lord High Executioner of Murder Inc., in October 1957 at the Grasso Barber Shop in what is now the Park Central Hotel, 870 7th Avenue. The barbershop later was converted into a Starbucks, but the chair where Anastasia was seated has been preserved by collectors and for a time was on display at The Mob Museum.

A couple of years after the Anastasia killing, Gallo attempted a revolt against his former allies in the Profaci crime family, sparking a bloody war, before being imprisoned on an extortion conviction in 1961. The Profaci family later was renamed the Colombo family.

After a prison term lasting about a decade, during which he purportedly read up to eight books a day, this son of a Brooklyn loan shark emerged as a self-styled painter and poet, impressing the Big Apple smart set. Among his pals during this period were comedian David Steinberg and actors Ben Gazzara and Jerry Orbach. It was Orbach who had starred, with a young Robert De Niro, in the 1971 film The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight, a spoof on the Gallo crew based on a 1969 comic novel of the same name by New York City newspaper columnist Jimmy Breslin.

Gallo’s star was on the rise. His second wife, Sina Essary, a former nun, told the Nashville Scene newspaper in 2007 that Gallo loved walking into the famed New York theater district restaurant Sardi’s. “You could hear a pin drop when he came in,” said Essary, who moved to Tennessee after her husband’s death to escape the hubbub of New York.

“People were mesmerized by him,” Essary said. “He had that quality that attracted people to him, no matter who they were. He was extremely intelligent, and he could talk about anything. He could talk about art, theater, politics, philosophy — all the things he had been reading about in prison.”

That would end with his shooting death, only three weeks after his marriage to Essary, at Umberto’s Clam House in Little Italy.

These days, with the annual Feast of San Gennaro fair set to occur this September on those same streets in Little Italy, some people inevitably will wander over to look at the site at Mulberry and Hester streets where Umberto’s once stood. The restaurant since has moved to a nearby building on Mulberry and still serves fried clams and steamed mussels. The location where Gallo was shot now is Da Gennaro, an Italian restaurant with nice sidewalk tables and a menu featuring chef’s specials such as osso buco and Barolo steak.

On an April night in 1972, Gallo and his party, celebrating his 43rd birthday, first attended a performance by comedian Don Rickles at the Copacabana nightclub on East 60th Street, then drove in a black 1971 Cadillac down to Lower Manhattan, entering Umberto’s at 129 Mulberry Street after 4 a.m. Among those with Gallo were his new wife and her 10-year-old daughter.

While the group enjoyed a second helping of shrimp, scungilli and clams, gunmen entered the restaurant firing away, wounding Gallo’s bodyguard and striking Crazy Joe in the left elbow, left buttock and back, according New York newspaper reports. In a pinstripe suit, Gallo stumbled outside and collapsed in the middle of Hester Street near his Cadillac that bore stickers advertising “Americans of Italian Descent,” according to an April 8, 1972, story in the New York Times. The civil rights group Americans of Italian Descent was a rival to one founded by Mob boss Joseph Colombo.

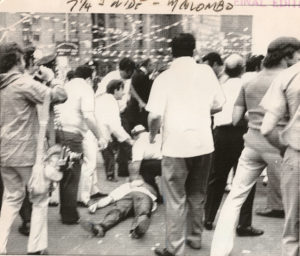

The killers were never identified, though many suspect a Colombo crew was responsible. Less than a year earlier, Colombo was critically injured in an Italian Unity Day shooting in Columbus Circle that some believe Gallo engineered. The gunman who wounded Colombo, a black man named Jerome Johnson, was shot dead immediately after he shot Colombo. Paralyzed, Colombo held on for seven years before dying at age 54 of cardiac arrest, thought to have been brought on by the lingering effects of the shooting.

More recently, Frank Sheeran, a Mob hit man who claimed he killed labor leader Jimmy Hoffa in 1975, also took credit for shooting Gallo. Sheeran’s assertions are detailed in the 2004 book I Heard You Paint Houses by former prosecutor Charles Brandt. Despite what Sheeran said, some Mob experts doubt he killed either man. A movie by director Martin Scorsese about Hoffa’s disappearance, based on Brandt’s book, is expected to be released next year.

At the time of his death, Gallo was a man about town, a media sensation with a book deal in the works from Viking. In that sense, he foreshadowed later celebrity wiseguys such as John Gotti.

Four years after the shooting in Little Italy, Gallo even became the subject of an 11-minute Bob Dylan ballad titled “Joey,” which received criticism for glorifying a criminal. Rock critic Lester Bangs called the song “one of the most mindlessly amoral pieces of repellent romanticist” trash ever recorded.

Dylan, whose musical body of work later won him a Nobel Prize in literature, saw it differently. “I never considered him a gangster,” Dylan said of Gallo. “I always thought of him as some kind of hero in some kind of way, an underdog fighting against the elements.”

While Gallo is not talked about as much these days, at one time he was ascendant in popular culture, a rebel Mob figure during the anti-establishment Vietnam War years, when gangster chic had cachet in certain circles.

Said writer Gay Talese, “He almost became one of the beautiful people.”

Larry Henry is a veteran print and broadcast journalist. He served as press secretary for Nevada Governor Bob Miller, and was political editor at the Las Vegas Sun and managing editor at KFSM-TV, the CBS affiliate in Northwest Arkansas. Henry taught journalism at Haas Hall Academy in Bentonville, Arkansas, and now is the headmaster at the school’s campus in Rogers, Arkansas. The Mob in Pop Culture blog appears monthly.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org