The first mobster in Las Vegas: Part 3

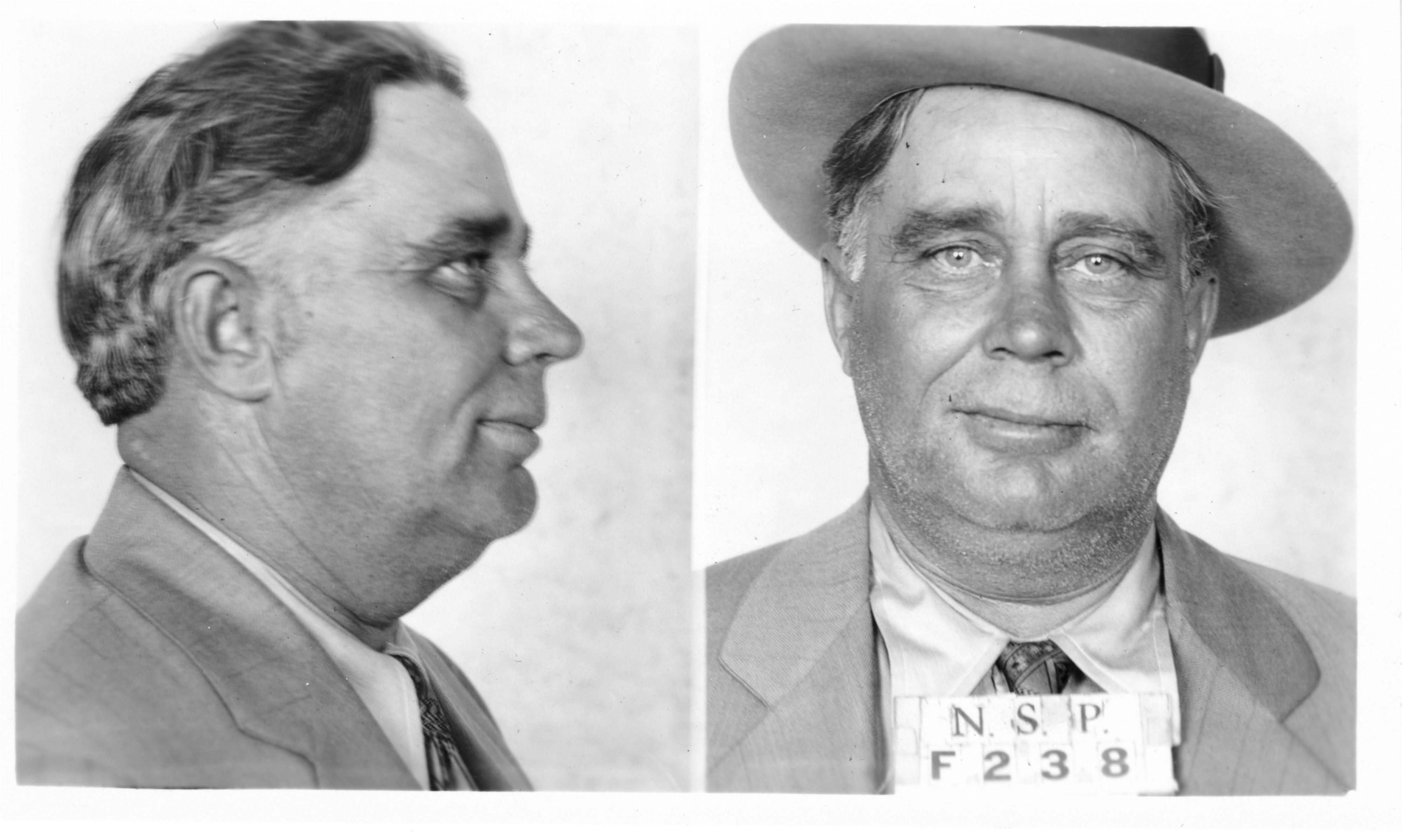

The law finally catches up with crime kingpin Jim Ferguson

Last of three parts

On June 20, 1929, Jim Ferguson, the king of the Las Vegas bootleggers, took the stand in federal court and denied wrongdoing. He also denied talking to the government’s undercover agents.

But two undercover federal agents said they had negotiated a deal with Ferguson to supply them with bonded liquor. The agents said Ferguson told them they did not need bonded goods to do business in Las Vegas as the people there had been pretty well educated to drink his moonshine. The agents also testified that Ferguson confided he had shipped significant quantities of alcohol into Los Angeles to go with a sizeable liquor business in other parts of Nevada.

The testimony and evidence was damning on the vice king. When the case went to the jury, the verdict arrived only 40 minutes later – guilty on all counts.

U.S. District Judge Frank Norcross delayed his sentencing of Ferguson so that he could hear the federal case against Mayor Fred Hesse, City Commissioner Roy Neagle and former Police Chief Spud Lake.

While Ferguson didn’t take the stand, the government’s attorney said he would show that Ferguson, as chief of the Las Vegas illegal liquor ring, collected protection money from other bootleggers with full knowledge of the Las Vegas officials, and that the city liquor ordinance was used as a club to force all liquor retailers to pay Ferguson money for protection.

Charles Bradshaw, the bootlegger whose 8-year-old son had been killed by a police officer’s gun, took the stand to testify about Ferguson’s bootlegging ring. He told the court he questioned Ferguson about Lake’s appointment as police chief. Bradshaw stated that Ferguson then replied, “If Lake wasn’t all right, we wouldn’t have him.”

Bradshaw said he paid Ferguson $50 per month for protection on the first day of each month, from January 1927 to June 1928. He claimed that after he stopped paying the fee, Las Vegas police arrested him three times within a short time span. Following his third arrest by (then Police Chief) Lake, he asked city officials for an explanation and was told there were orders to keep arresting him until he either quit the liquor business or paid Ferguson.

Joe May, a Las Vegas police officer who once served as acting marshal under then-Police Commissioner Roy Neagle, testified that Neagle once ordered him to “lay off” enforcing the law against the Green Lantern Saloon after the business had reopened following a raid.

May testified that when he informed Neagle he had a search warrant and was on his way to raid the Green Lantern for selling illegal liquor, Neagle went to the saloon before he did, and when the officers raided the place, they found nothing incriminating.

May and another Las Vegas officer testified that when each of them told Neagle they had information that liquor was being sold on Block 16, Neagle told them to leave the alleged violators alone “as long as they don’t go too strong.”

Undercover federal Prohibition agent Harry Drew took the stand and, once again, related his conversation with Ferguson while posing, along with another agent, Roland Godfrey, as Canadian rumrunners. Drew testified that Ferguson bragged of having the finest stills in the country and was “manufacturing huge qualities of alcohol for the California market.” He stated that Ferguson told him he doubted if the people of Las Vegas would take very kindly to smuggled bonded goods, as they preferred his moonshine whiskey.

Ferguson, Drew added, told him not to worry about the city police, that he himself hired and fired the officers in Las Vegas, and held the balance of power in elections.

Agent Godfrey corroborated Drew’s testimony.

After hearing the testimony, Judge Norcross ordered a directed verdict of acquittal on Hesse and Neagle on charges of conspiracy to violate national liquor laws. Norcross said the evidence presented against Hesse and Neagle was not incriminating enough to hold them.

He also discounted the testimony of two Las Vegas police officers who said they were ordered to “lay off” certain saloons. The officers, the judge ruled, did not provide evidence that Neagle or the mayor had been referring to trafficking illegal liquor, and that Neagle’s orders likely indicated a city policy, not a conspiracy.

Judge Norcross said the only evidence offered by the government to link Mayor Hesse with a conspiracy was the fact that he asked to transfer federal illegal liquor cases to the city court.

Norcross, perhaps giving the city of Las Vegas wide latitude, said he was not ruling on whether this was good city government, but that it was evidently a revenue measure for the city of Las Vegas.

Although the cases against Hesse and Neagle were tossed out of court, the judge said there was enough evidence to hear the case against Lake. On June 26, 1929, a jury heard the conspiracy case against the former police chief, including testimony from Mayor Hesse. Jurors took just 50 minutes to return a not-guilty verdict, exonerating Lake.

With the cases against the three Las Vegas city officials now out of federal court, the only thing left was Ferguson’s sentencing. A report from the U.S. attorney for Nevada included three key questions and answers about Ferguson:

• “What is his principal business or trade? Bootlegging.”

• “What is the character of his associates? Bad.”

• “What is your opinion as to the criminal tendencies of the prisoner? Do you regard him as a menace to society, a habitual criminal, or as a man who had made a mistake?” The U.S. attorney’s answer to the third question: Ferguson was a “Habitual Criminal.”

After reading the report, the federal judge sentenced Ferguson to serve one year and one day in prison. But in a move that surprised many, the judge added a provision allowing Ferguson to be released in a few months if he paid a fine. Ferguson would have been out of prison before Christmas.

But days before Thanksgiving 1929, the Justice Department stepped in to cite a previous court ruling stating that while federal judges have the authority to grant probation at the time of sentencing, they do not have the “authority to sentence a man, and then provide for future probation.”

On Friday, May 17, 1930, Ferguson walked out of prison, 41 days early based on time off for good behavior. In his absence, new faces had taken over the bootlegging and vice operations Ferguson had once controlled.

When he returned to Las Vegas, he found that his wife still ran the Double O brothel on Block 16, and a few members of his old gang were also in town. But while he was able to move back to his old haunts, he found out that the balance of power in the city’s underworld had changed.

Mobsters from Southern California had begun to make moves in Las Vegas. Individuals with money and power from Ely had set up shop. Locals, such as the Stocker family, had become strong enough to fight back against “protection” fees. And local law enforcement was not as easily corruptible as it had been.

For a few months, Ferguson laid low and took time to decide what his next step would be. Then on Christmas night, December 25, 1930, at one of Ferguson’s old booze lounges, the Green Lantern, one of the most daring holdups staged in Las Vegas in many years took place. Witnesses spotted Ferguson’s blue Cadillac in the parking lot at the time of the robbery.

Four days later, a local newspaper reported that the “Las Vegas underworld was rocked to its very foundations with the arrest of Jim Ferguson, former liquor king and ex-convict.” The new sheriff of Clark County, Joe Keate, arrested Ferguson and two other men in connection with the robbery of the Green Lantern. The sheriff arrested Ferguson on suspicion of being the “mastermind” behind the robbery.

Following a preliminary hearing in Las Vegas, a judge dismissed the charges against Ferguson but bound the other two men over for trial.

A few weeks later, police arrested Ferguson again when one of the defendants claimed he had helped plan the robbery. But the new charge did not hold up in court and once again Ferguson was released.

In the local press, Ferguson’s notorious position had fallen to that of “one-time reputed King of the Las Vegas Underworld.”

Sheriff Keate told a news reporter that, “There’s no fooling around this proposition, this town is going to be cleared of undesirables pronto, and we’re starting in today.”

Not one to settle down yet, Ferguson again put himself in hot water. Police put him in handcuffs after an altercation on Block 16 during which he allegedly threatened the lives of one or two individuals. Keate declared that he would have Ferguson charged with vagrancy as the opening round in a drive by local law enforcement to purge Las Vegas of “troublemakers and undesirables.”

Ferguson paid his fine on the vagrancy rap and began looking for new territory beyond Las Vegas. He found it in Utah. A gang of safe crackers began hitting communities throughout that state. On October 18, 1931, authorities in Logan City, Utah, nabbed Ferguson, who used the alias “Sam B. Harris.” Officers arrested Ferguson and two others after they broke into a safe in Logan City and stole a car. Ferguson faced auto theft and burglary charges.

After he pleaded not guilty, prosecutors offered Ferguson a plea bargain – they would charge him only with third-degree burglary if he would plead guilty. He accepted the deal. A judge sentenced him to one year and one day in the Utah State Prison and required him to pay a fine and court costs totaling $1,820.58.

On November 7, 1932, the prison released Ferguson. This time, he headed to the far Northwest.

Not long after he set foot in Spokane, Washington, local law enforcement made it clear they were not happy with his presence. At the end of April 1933, the law charged him with vagrancy and he spent 30 days in jail.

Ferguson headed back to Southern Nevada and rejoined what was left of his gang. But local police and federal agents were on his tail, believing he and his gang were responsible for a recent crime wave that hit Lincoln County, Nevada, and southern Utah.

He continued to pay the consequences for his continuing life of crime. On October 25, 1933, Utah officers arrested Ferguson and accused him of robbing a railroad boxcar at Lund, Utah, a week earlier. Based on Ferguson’s arrest, a newspaper credited Southern Nevada law enforcement officers, working with railroad police, with “breaking up one of the most dangerous gangs of criminals operating in Nevada.”

Before the year was out, a federal court indicted Ferguson on robbery charges, found him guilty, and, on December 12, 1933, sent him to federal prison. Two days later, Ferguson arrived at the U.S. penitentiary at McNeil Island, Washington, to begin a stretch of three years and six months.

After his release from the federal prison, like a broken phonograph record, word spread that Ferguson was headed back to Las Vegas. Waiting for him was his wife, Magness, who after all this time still managed the Double O brothel on Block 16.

But the known release of the city’s most infamous career criminal in 1936 brought trouble for Magness. On February 25, the Las Vegas City Commission met to discuss pulling all the licenses issued to Magness. Officials charged her with allowing underage girls in her “sporting house.”

Ferguson and Magness received some unexpected local support. City Commissioner M.E. Ward said the charges against the Double O were simply a “frame-up” job due to an “old political feud between Sheriff Joe Keate and James Ferguson, one-time Las Vegas underworld king.”

At a City Commission meeting, Ward advised his fellow commissioners that Ferguson would be released from the penitentiary shortly and probably would be back. But Ward defended Las Vegas as a place for visitors who enjoy taking their children to local bars.

“This is a supposed to be a wide-open town and we attract tourists on that basis,” Ward said. He asked whether the city would tell its tourists that “they can’t take their children into the taverns while they buy a drink?”

Ward said he had visited the taverns in Las Vegas and had seen parents with their underage children in all of them. The city commissioner closed his arguments by saying he had seen parents in these taverns feeding babies beer.

Despite Ward’s plea, his fellow commissioners voted to close the Double O. Magness would soon be back in business, but the end of her long career on Block 16 was near.

As for Jim Ferguson, one-time King of the Las Vegas Underworld, there is no record of him ever returning to Las Vegas.

What happened to them?

Mayor J. Fred Hesse

After a jury found him not guilty of all federal charges in 1929, Hesse returned to Las Vegas to face a recall election. The mayor survived the recall, but announced he would not run for re-election and instead concentrate on his car repair business. “I’m (through) with politics, I’m going to devote all my time to running the new garage,” he said.

When he died in 1941 at age 67, a newspaper remembered Hesse for his “picturesque and adventuresome career.”

A trained engineer, Hesse came to Las Vegas in 1917 to develop plans for a private firm to build a dam across the Colorado River. As mayor, Hesse took the city’s financial standing from red to black and improved city streets, sewers and street lighting. The revenue to pay for it came largely from fines paid by bootleggers.

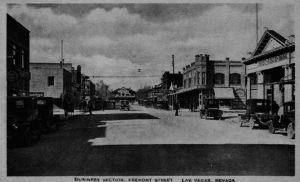

After his death, the local press did not mention the troubles he had faced during Prohibition. A front-page obituary in one local newspaper did say Hesse “established the first police department in a definite headquarters … in a residence occupying the corner of the alley” behind what is now the Binion’s Hotel.

Las Vegas City Commissioner Roy Neagle

After his acquittal on all charges in federal court, Neagle decided to devote full time to his retail store in Las Vegas. After completing his two-year term as police commissioner, he did not seek re-election.

Las Vegas Police Chief Robert “Spud” Lake

After a jury found him not guilty in the death of young Sheridan Bradshaw, and his acquittal on federal alcohol charges, the former police officer went to work at the Boulder Club casino on Fremont Street. In addition to handling security at the club, he also ran its Big Wheel game for a while.

Local news reporters interviewed Lake over the ensuing years. In one case, in December 1943, a reporter asked him about “gangsters and hoodlums.” The reporter wrote that in response, Lake did “a slow burn” and claimed that Las Vegas “never has been a tough town.”

In 1978, when Lake was in his early 80s, he was asked by reporter Brad Peterson about Las Vegas in the Prohibition years. “We didn’t bother much with it,” Lake replied. “There was a fine of so much a month. The biggest part of them would come in themselves and you didn’t have to go and get them. They’d come in, pay their fine and go about their business.”

In the same interview, Lake confirmed that Jim Ferguson and one of Ferguson’s partners paid the city the fines owed by bootleggers. Peterson wrote that according to Lake, “None of the money … went to the police officers. It all went to the city, which tolerated a business profitable to the city coffers.”

Lake died in Las Vegas at age 87.

Vera Magness Ferguson

Magness, who may have been legally married to Jim Ferguson, operated the Double O brothel on Block 16 for more than a decade. In 1936, though commonly referred to as “Mrs. Ferguson” in Las Vegas, Mr. Ferguson told prison officials at the time that he was “single.”

By 1941, the red light district of Block 16 had long seen its best days and the city began a successful effort to close down the block’s vice services amid complaints from the brass of the U.S. military stationed outside Las Vegas.

Magness served as madam of the Double O brothel until August 1941. At the end of 1941, she married a taxi driver. Elderly and near death in 1965, her last known job was as a maid at a motel in the 300 block of North First Street.

Jim Ferguson

When Ferguson got out of federal prison in 1936, there were unconfirmed reports that he returned to Las Vegas. But in truth the city’s former bootlegging and vice kingpin had disappeared.

After arriving in Nevada in mid-1924, Ferguson spent half of his time behind bars – inside city and county jails and state and federal prisons. Whether he was tired of prison time and went “straight” for the rest of his life, or used another one of his many aliases, Ferguson dropped out of sight. His death, whenever that occurred, was not recorded by Las Vegas newspapers.

Robert Stoldal, a longtime television news executive in Las Vegas, is a Las Vegas historian and member of The Mob Museum’s Board of Directors.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org