Frank Sinatra’s terrible, horrible, no good, very bad year

In 1963, after a Chicago mobster’s forbidden visit to a Lake Tahoe casino, the famous crooner forfeited his Nevada gaming license

In a gift shop at the Sands hotel-casino in Las Vegas, Sammy Davis Jr., practicing with a golf putter by a display, spotted a Nevada gaming official and asked to have a word with him.

The state official, Ed Olsen, having gone toe-to-toe with Davis’ friend Frank Sinatra for allowing a mobster inside Sinatra’s Lake Tahoe casino, remembered thinking, “Oh, God, here comes a brawl for sure.”

As recalled in James Kaplan’s 2015 book Sinatra: The Chairman, Olsen instead received a thank you from Davis for putting Sinatra in his place.

“He’s needed this for years,” said Davis, a popular performer whose talents included acting, singing and dancing. “I’ve been working with him for sixteen years, and nobody’s ever had the guts to stand up to him.”

Standing up to Sinatra in 1963 was not easy. The former saloon singer from Hoboken, New Jersey, was a stage and screen sensation by then. Only three years earlier, in 1960, Sinatra, Davis and others from an elite circle of entertainers known as the Rat Pack starred in the Las Vegas heist movie Ocean’s 11. This month marks the movie’s 60th anniversary.

The Rat Pack, which also included Dean Martin, Peter Lawford, and Joey Bishop, attracted attention to Las Vegas during these years with high-spirited shows in the Copa Room at the Sands, where Sinatra and Martin were part owners. Among the group’s friends were John F. Kennedy, Marilyn Monroe and others from politics and entertainment.

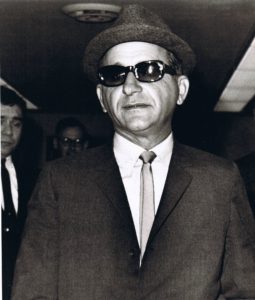

But it was Sinatra’s association with the Chicago Outfit’s Sam Giancana that caught the attention of Nevada gaming officials and culminated in the singer forfeiting his partial ownership in Lake Tahoe and Las Vegas casinos.

The problem reached a boiling point in the summer of 1963, when the state challenged Sinatra about Giancana being at the Cal-Neva Lodge, on the north shore of Lake Tahoe at Crystal Bay. Lake Tahoe is in the Sierra Nevada mountains near Reno.

Sinatra was the principal licensee at the Cal-Neva, where the California-Nevada border — thus the name, Cal-Neva — runs through the swimming pool and now-shuttered main lodge. Gambling was permitted on the Nevada side.

Sinatra fired back in an August 31 phone call with Olsen that included an implied threat and a barrage of obscenities and insults. Sinatra even called Olsen, a former Associated Press reporter who used a cane because of childhood polio, “a crippled S.O.B.”

Giancana had been at the Cal-Neva that July with girlfriend Phyllis McGuire during her booking in the Celebrity Room. Phyllis is one of the singing McGuire Sisters. Giancana was listed in Nevada’s Black Book of persons prohibited from entering any casino statewide. He even had been involved in a fistfight with another man while there.

Giancana and McGuire were staying in Chalet 50, a cottage on the Cal-Neva grounds, said Guy W. Farmer in a telephone interview from his home in Carson City. Farmer, an 84-year-old former Gaming Commission and Control Board spokesman, still has an original copy of the state’s first Black Book, which he received while working as a $10,000-a-year state gaming employee. Giancana’s name is in it.

Farmer said Sinatra “had been warned about running that kind of establishment.”

The year before, in the summer of 1962, Giancana was at the Cal-Neva many days, sometimes in golf attire and usually accompanied by Sinatra, according to retired journalist John Jekabson, then a student at Occidental College in Los Angeles working at the lodge as a seasonal pot washer and busboy.

One of the other workers told Jekabson who Giancana was and advised him to stay out of his way. To everyone there, the Chicago mobster, rumored to be a secret part-owner of the Cal-Neva, was just known as “Sam.”

“I was surprised he was there so openly,” the 79-year-old Jekabson said by phone from his home in Oakland. Jekabson, an artist, secretly drew sketches of Sinatra and Giancana during that summer. He still has the sketches, as well as Cal-Neva pay stubs, and even saved some of the matchbooks he collected while working there. The matchbooks identify the property as “Frank Sinatra’s Cal-Neva.”

Earlier sightings of Giancana are what prompted state officials to warn Sinatra not to host notorious figures on the property. However, Sinatra, a major star, “was going to do it his way,” Farmer said.

“Sinatra was mobbed up his whole life,” said Farmer, who had worked for the Associated Press at the Capitol in Carson City before taking the state job.

This level of scrutiny aimed at JFK’s friend did not escape the president’s attention, according to Hang Tough!, the oral history of former Nevada Governor Grant Sawyer, who died in 1996 at age 77. The book was published in 1993 by the University of Nevada Oral History Program.

In an open-air car on the way to the Las Vegas Convention Center, Kennedy spoke with fellow Democrat Sawyer about Sinatra’s casino licensing problems.

“What are you guys doing to my friend, Frank Sinatra?” the president asked. The implication: Go easy on him.

“Well, Mr. President,” Sawyer said, “I’ll try to take care of things here in Nevada, and I wish you luck on the national level.”

Having seen a memo of Sinatra’s obscenity-laced phone call, the governor told Olsen not to back off. “Do not be intimidated by him,” Sawyer told the Gaming Control Board chairman.

In his oral history, Sawyer, a former prosecutor from Elko in northeastern Nevada, said Sinatra was a “very abusive guy.”

“My experience with him has been that he sets his own rules,” Sawyer said. “He does his own thing, regardless, and he has violated laws with impunity and bought his way out of most problems if he could.”

The 1963 episode turned out to be one Sinatra couldn’t badger or buy his way out of.

Just weeks after his phone call with Olsen, Sinatra announced he was giving up his ownership in Nevada casinos. The announcement came from his attorney, Harry Claiborne, on October 7. More than two decades later, Claiborne, by then a federal judge, was imprisoned for falsifying tax returns and, in a U.S. Senate impeachment conviction, was removed from the bench. He died in 2004 at age 86 of a self-inflicted gunshot wound.

Through his attorney, Sinatra asserted that he gave up the casino investments because he was finalizing a deal with Hollywood executive Jack Warner, who was “opposed to involvement in gaming,” according to the New York Times.

Farmer, now an award-winning political columnist at the Nevada Appeal newspaper in Carson City, said the truth is Sinatra recognized he had drawn a losing hand against the state and its Black Book ban on mobsters being in casinos.

“Sinatra caved in,” Farmer said in an oral history published by the University of Nevada, Reno. “He realized he couldn’t win under our law, as written, and he caved in and threw in his license.”

Giancana was upset with Sinatra for yelling at the gaming official and calling him a cripple, believing a calmer approach might have led to a 30- to 60-day suspension but not a loss of the casino license, according to Kaplan’s book, Sinatra: The Chairman.

Giancana told a friend, “Frank has to get on the phone with that damn big mouth of his and now we’ve lost the whole damn place.”

According to the book, Sinatra pointed the finger at Giancana, saying the mobster “shouldn’t have been there in the first place.”

“Look at the trouble he caused,” Sinatra said. “This is his fault, not mine.”

Sinatra’s fortunes turned around years later.

In 1981, when Sinatra was 65, he regained a key employee casino license in Nevada, telling state gaming regulators he did not invite Giancana to the Cal-Neva in 1963 or even see him there. Once he learned Giancana was on the property, he ordered casino officials to ask him to leave, Sinatra told the panel.

Sinatra’s attorney at this 1981 hearing, Bill Raggio, a Republican state senator and former Reno prosecutor, said a Gaming Control Board “inquiry had not turned up evidence” of Sinatra having Mafia ties, according to the New York Times.

”Few persons could stand up to the rigorous, exhaustive scrutiny, the penetrating depths of this type of investigation,” said Raggio, who died in 2012 at age 85.

Farmer, who listened in on an office phone line in 1963 when Sinatra berated his boss, later went to work overseas, but he recently said he was not happy about the result of that 1981 hearing.

“They drooled all over him,” Farmer said.

Over the years, more would come out about Sinatra’s relationship with underworld figures.

In his 1997 book The Dark Side of Camelot, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Seymour Hersh quotes Sinatra’s daughter, Tina, saying it was her understanding that Sinatra met with Giancana before the 1960 presidential election, at Kennedy family patriarch Joe Kennedy’s urging, to get “the unions to vote” for JFK in the key states of Illinois and West Virginia. Kennedy defeated Republican Richard Nixon in a close election that year. High-ranking mobsters later felt betrayed when Kennedy appointed his crime-fighting brother, Robert, as attorney general, leading to increased federal scrutiny of the Mafia.

In Hersh’s book, Tina Sinatra said her father grew up in New Jersey around gangsters and that mobsters controlled the nightclubs he later performed in.

“The power of an entertainer and the power of a mobster — it’s all very much part of America,” she told Hersh.

She said her father had an “absolute commitment to friends and family.” “Frank’s affiliation with Sam Giancana and other mobsters — we all understand that,” she said.

Giancana was shot to death at age 67 at his home in Oak Park, Illinois, a Chicago suburb. No one ever has been held criminally responsible for the 1975 killing.

In 1963, Sinatra’s association with Giancana was not the only challenge the star faced. The final months of that year came with other setbacks for him — and the country. President Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas on November 22, and Sinatra’s 19-year-old son was kidnapped from a South Lake Tahoe casino in December. Frank Sinatra Jr. was released unharmed a couple of days later.

After the kidnapping, Frank Sinatra, concerned about not having change for a pay phone in an emergency like the one involving his son, always had 10 dimes with him and even was buried with 10 dimes.

Sinatra died in 1998 of a heart attack at age 82. In addition to the dimes, he was buried with a bottle of Jack Daniel’s whiskey, a pack of Camel cigarettes and a Zippo lighter, according to the Associated Press.

On CNN’s Larry King Live, Tina Sinatra said her father’s habit of carrying dimes “came from Frankie’s kidnapping, maybe before.”

“He never wanted to get caught not able to make a phone call,” she said.

Stories like this reveal a different side to Sinatra, indicating a complex personality beyond the bullying he exhibited toward Olsen and others. Farmer noted that Sinatra did have a positive impact on the state as a popular entertainer and as a champion for civil rights at a time when Nevada was viewed as “the Mississippi of the West.”

Over time, with the Rat Pack members moving on and dying, that era dissolved into a modern period of phenomenal growth and transformation in Las Vegas. The Sands was closed and demolished in 1996. The Venetian hotel-casino, with gondola rides available in water-filled canals, opened at that site on the Las Vegas Strip in 1999.

Many physical reminders of that eventful last half of 1963 in Northern Nevada also have gone through changes. At Lake Tahoe, the Cal-Neva remains closed, though news stories indicate it might open again someday.

Back in Las Vegas, a plaque went up at the Venetian near where five of the famous Rat Pack stars were standing for a photo in front of the iconic Sands sign when their careers were soaring. “A Place in the Sun” is how the sign describes the Sands. All five are in suits and neckties, a couple of them squinting in the sunlight, and only one, Sammy Davis Jr., with a loosened tie. On the ground beneath the plaque are replica footprints showing where the five were standing that bright day long ago.

Larry Henry is a veteran print and broadcast journalist. He served as press secretary for Nevada Governor Bob Miller, and was political editor at the Las Vegas Sun and managing editor at KFSM-TV, the CBS affiliate in Northwest Arkansas. Henry taught journalism at Haas Hall Academy in Bentonville, Arkansas, and now is the headmaster at the school’s campus in Rogers, Arkansas.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org