Ninety Years Ago Today, Prohibition Ended at 2:32 p.m. Pacific Time

Minutes after Utah became the final state needed to ratify the 21st Amendment, repeal parties ensued

On Tuesday, December 5, 1933, the unprecedented repeal of a constitutional amendment went into effect, officially relegalizing intoxicating liquors in the United States. Americans could buy a legal drink for the first time in more than 13 years.

Across the nation, people celebrated, eager to exercise their legal right to booze. Some threw repeal parties to mark the occasion. Although repeal parties were more celebratory than the pre-Prohibition “last call” parties of 13 years earlier, they certainly were not as wet or as numerous. When last-call parties mourned the loss of legal liquor on January 16, 1920, hotels, restaurants and saloons were eager to sell the last of their supply. Booze flowed freely, and many people staggered home bleary-eyed in the early morning of January 17.

The landscape after repeal was more complicated. Nineteen states had the necessary laws in place to legalize liquor as soon as the final state ratified the 21st Amendment. For other states, access to liquor, and even wine and beer, would take days, weeks, months or years. A combination of remaining state Prohibition laws and regulatory issues, as well as limited liquor stock in the United States, did not make it easy for would-be revelers to drink to excess.

December 5, 1933, broke the seal on a situation that had been bubbling for almost half a decade. In 1929, violence related to liquor trafficking increased — as evidenced by the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in Chicago — and the Great Depression caused massive upheaval in American society. People began expressing greater frustration with Prohibition, and they were ready for a change.

From start to finish, the repeal process took less than 10 months. The House of Representatives passed the Prohibition repeal act on February 20, 1933. Yet lightning-quick ratification was hardly a foregone conclusion. On the day the act passed, congressional forecasters pegged ratification at about two years, but the sweeping tide of “wet” advocates who pushed for repeal made haste. At the time, this was the second quickest ratification process in U.S. history. It was beat only by the wild no-brainer of the 12th Amendment, which created the combined presidential-vice presidential ticket, replacing the ineffective system in which the presidential runner-up became vice president.

By November 2, 1933, 30 states had ratified the amendment. Experts began projecting a clear path to ratification before the end of the year. On December 5, Pennsylvania, Ohio and Utah all approved the amendment in state conventions selected specifically to vote on the law. Utah became the final state necessary to ratify the amendment at 3:32 p.m. mountain time.

The following day, both Maine and Montana also ratified the amendment, although unnecessary for the law to pass. Ultimately, 38 states ratified the Amendment, but only 36 were required. South Carolina unanimously rejected the amendment, North Carolina rejected a measure to hold the required state convention, and the other eight states never moved to hold a state convention at all (Alaska and Hawaii were not yet states).

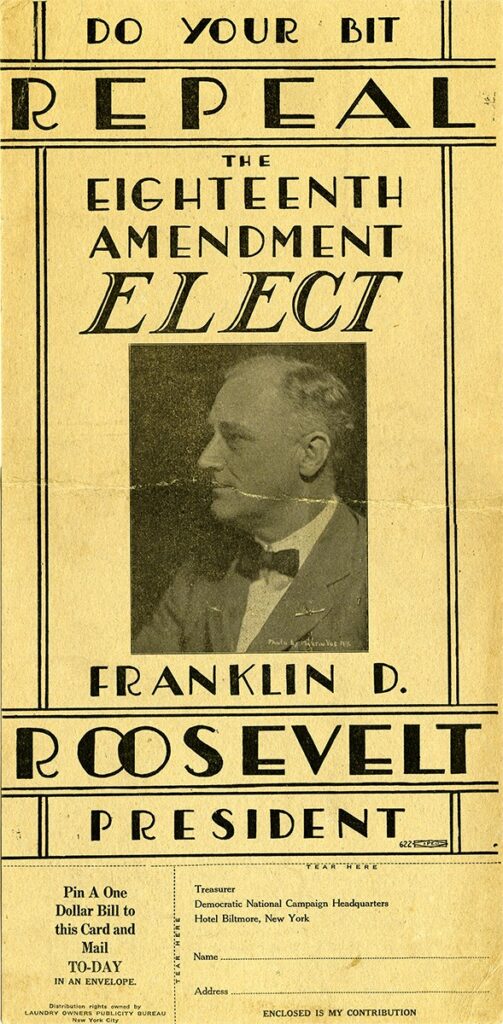

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a vocal advocate for repeal, immediately issued a proclamation announcing the ratification of the amendment. Legend has it that he then celebrated with a happy hour martini; it was, after all, already five o’clock in Washington, D.C.

But the phrasing of the proclamation is important. Even for wet politicians such as Roosevelt, repeal did not necessarily mean a desire to return to the pre-Prohibition status quo. In his proclamation, Roosevelt expressed, “I trust in the good sense of the American people that they will not bring upon themselves the curse of excessive use of intoxicating liquors, to the detriment of health, morals and social integrity.” He also asked for “the wholehearted cooperation of all our citizens to the end that this return of individual freedom shall not be accompanied by the repugnant conditions that obtained prior to the adoption of the 18th Amendment and those that have existed since its adoption.”

Roosevelt echoed sentiments heard from many who once supported Prohibition before switching to the repeal cause in the late 1920s. Urging Americans to follow both the letter and the intent of this new law, Roosevelt expressed a desire for citizens to practice moderation and denounced the saloons that had existed before Prohibition. His proclamation focused not only on temperance and a request for Americans to abide by the law, but on the idea that a return to legal liquor also meant a return — and in many ways an increase — in regulation of both drinking establishments and alcohol itself.

Political proclamations aside, what did the night of repeal actually look like? How great were the parties?

Although some states expedited licensing in the lead-up to repeal, many jurisdictions still had very few establishments with liquor licenses. In Las Vegas, just nine tavern licenses, five drugstore package permits and one cabaret license were issued ahead of repeal.

In Brooklyn, New York, only two hotels had full liquor licenses in place by the evening of December 5, according to the Brooklyn Times Union. In an article from the following day, repeal night was described as restrained, with no reported arrests for drunk or disorderly conduct as of 11 p.m. on the 5th. The reporter did note that “many young people…seemed in awe of the wine list.” And although many establishments did serve liquor without full licensure in place, what they had on hand was limited.

One notable exception to the lackluster celebrations was Chicago. Even before the final state ratified repeal, large crowds filled Chicago Loop bars and stayed until closing time. At the Hotel Sherman, bartender Danny Monahan, who also tended bar on the last day before Prohibition began, led a team of assistants on the afternoon and evening of repeal. At 4:35 p.m. central time, just three minutes after Utah ratified repeal, a bellboy entered and rang a handbell that signaled liquor could be sold again.

Four blocks away at the Palmer House, officials stated that by midnight, guests had consumed 50 cases of bourbon and rye, 25 of Scotch, 50 of gin, 75 of wine and champagne, 10 of cordials and 20 barrels of beer. Chicago had been wet during Prohibition, and repeal showed no signs of dampening the fun.

A Chicago Tribune article from December 6 noted that to expedite drink service, many hotels and bars eschewed the former custom of serving patrons with a glass and decanter and simply poured drinks straight from the jigger to a waiting glass. Although this was reported as a time-saving measure meant to aid in the fulfillment of nonstop drink orders, it was also likely a result of rusty or novice bartenders. America’s best bartenders fled to Europe during the 13 years of Prohibition. While many skilled barkeeps still served in the nation’s speakeasies, by 1933, a whole generation of young adults had no experience at all with legal liquor.

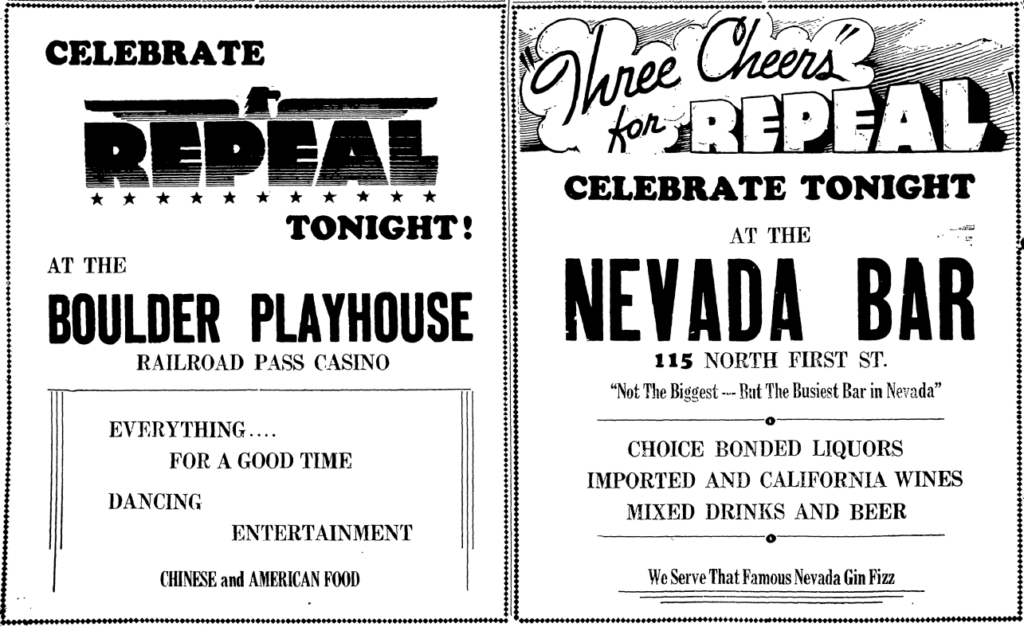

In Las Vegas, where Prohibition had not been strictly enforced since the repeal of a state companion law in 1923, the night of repeal was largely business as usual. In the December 5 edition of the Las Vegas Evening Review-Journal, three area bars, the Apache Hotel bar, the Nevada Bar and the Boulder Playhouse, took out quarter-page ads promoting repeal parties to be held that evening. Three drugstores also celebrated the return of legal package liquor in quarter-page ads.

Based on these advertisements, one might think that December 5, 1933, was quite raucous, but an editorial the following day painted a different picture:

“In many states there was a big hurrah and plenty of liquor being gurgled down parched throats. That, however, was in sections where prohibition had placed some restraint on the sale of liquor, or where wealthy play-boys and play-girls took advantage of the opportunity for one of their celebrations which come at the least excuse. Nevada has worried little about prohibition these later years, and has reached a stage of real temperance as a result. There will be little change in the actual drinking habits of the people of this state as a result of repeal.”

It is certainly an understatement that the city had reached any demonstrable state of temperance, but the parties were reportedly low-key affairs.

If muted Repeal Day parties are evidence of limited liquor supply, legal red tape and regulations, they are also evidence of the realities of Prohibition. Prohibition never outlawed the right to drink. It outlawed the manufacture, transport and sale of intoxicating beverages. And for the 13 years, 10 months and 19 days that Prohibition was in effect, mobsters, moonshiners and rumrunners supplied thirsty Americans with liquor regardless of its legal status.

Speakeasies existed everywhere. In New York alone, experts estimate more than 30,000 speakeasies operated during Prohibition. In Las Vegas, a community with fewer than 9,000 people in 1930, there were more than a dozen speakeasies raided and closed — temporarily — in the first two months of 1928 alone.

The majority of Americans heaved a sigh of relief on Repeal Day, and many also raised a glass. Although contemporary press coverage painted a picture of quiet, refined parties, many a photo reveals exuberant crowds pressed elbow to elbow, ready to sidle up to the first legal bar in sight since 1920. Nevertheless, Americans continue to celebrate Repeal Day as a return to personal liberty in the form of a pint glass, highball or champagne flute.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org