Working for Lucky and Dutch

Stanley Grauso celebrates 103rd birthday at Mob Museum, recalls early years as gangster for Lucky Luciano, Dutch Schultz

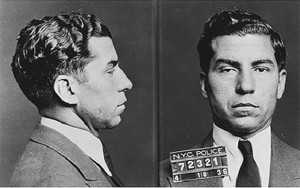

Stanley Grauso, a real Prohibition-Era hoodlum who died recently at age 104, sat down with The Mob Museum two days before his 103rd birthday to reminisce about his life in bootlegging, prostitution and the numbers rackets in Connecticut and New York in the 1920s and 1930s, the several people he claims to have shot dead and his experiences working for two of the most notorious gangsters in American history, Charles “Lucky” Luciano and Dutch Schultz.

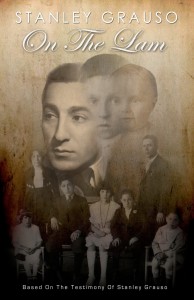

Blessed with a remarkable memory, Grauso recently co-wrote a self-published autobiography, On the Lam, tracing his life growing up in his native Bridgeport, Connecticut, as a mid-level hood during and after Prohibition. Grauso’s stories are difficult to verify. Sometimes his statements sounded a bit cliché. But his responses to our questions about events in his gangster past were spontaneous and detailed.

Grauso, born in 1912, was fifteen when his Mob-connected father, Alexander, a bail bondsman for organized criminals, got him a job working for brothel owner “Don Ernesto” Cozza during Prohibition. At age seventeen, Grauso joined up with veteran hood Phil Musica to smuggle liquor from Canada in trucks for Cozza.

During one such run, they parked at a rest stop and Musica got out to meet a rival mobster. The mobster shot and killed an associate of Musica’s, then pointed the gun at Musica. Grauso said he exited the truck and shot the mobster dead, saving Musica’s life. Musica later admitted his real name was Frank Coster and that he owned a pharmaceutical company used as a front for bootlegging liquor and trafficking military weapons. He told Grauso that two brothers, Joseph and Barnett Cohen, had threatened to expose Musica’s operation. He asked Grauso to assist him in killing them. Grauso, who said he was so close to Musica and would do anything for him, agreed. Grauso said he fatally shot Joseph at a racetrack in Jamaica, New York. Musica gunned down Barnett at another location.

“In 1929, nobody found out – until today – who whacked the two of them,” Grauso said.

Musica told him to lay low for a while, one of the many times Grauso said he had to stay “on the lam,” frequently moving from place to place to avoid recriminations.

With Prohibition about to end in the early 1930s, Grauso said he took up with a hoodlum named Big Dietz, who managed brothels in Albany and elsewhere in New York State for Luciano. Grauso, who worked as an enforcer at Luciano’s brothels with Dietz, said he recalled meeting Luciano at the kingpin’s coffeehouse in midtown Manhattan.

Courtesy of the New York City

Municipal Archive

“Lucky, he was a son of a bitch, he was. See, I seen the way he worked,” he said. “When he took over those cathouses, if those madams … he’d whack ’em. He’d break the furniture. He was crazy, that Lucky. You couldn’t get out of line with him. He’d shoot you right away.”

Luciano assigned Grauso and Dietz to travel to five brothels and force the madams to give Luciano a part of their profits in exchange for protection. According to Grauso, Thomas Dewey, a private lawyer before he was appointed special prosecutor to fight organized crime in New York in 1935, was romantically involved with a woman known as Madam Cory, who ran a brothel Luciano owned in Albany. Not only that, but Luciano was also seeing Cory at the time.

“We finally got him (Dewey) as a lawyer to protect the cathouses, you know, in case of raids and stuff like that,” Grauso said. “He went for Cory. It ended up in a fight, who’s going to take care (of Cory). Anyway, they ironed all that out. He got so familiar with Cory, the madam, he wanted to take charge, you know. And Lucky, it was his mistress, too.”

While collecting protection payments for Luciano’s brothels, Grauso and Dietz also had side deals – unbeknownst to Luciano – drawing extra cash from liquor sales and loansharking in the houses. That was a dangerous proposition because Luciano would likely kill them if he found out, and apparently he did. One night in the mid-1930s, while Grauso and Dietz drove to a brothel in Troy, New York, a couple of cars followed them and blocked the driveway. A fight ensued but Grauso realized he forgot his gun and Dietz was killed. One of the hit men held the gun to Grauso’s head but the gun jammed and Grauso was able to escape.

Grauso changed affiliations and started working for Dutch Schultz in New York City after meeting Otto “Abbadabba” Berman, a top player in Schultz’s horse-race fixing and numbers rackets. Grauso ended up working the numbers, or lotteries, for Schultz. Grauso said that at one point, Schultz “killed a lot of blacks” in the Harlem district in order to establish himself in the numbers racket there.

Over the years, Grauso said he’s always found it funny when seeing Schultz portrayed in films by tall actors because Schultz was actually only about five feet tall.

“The Dutch, first of all, he was cheap!” he said, laughing. “He wouldn’t buy a suit unless it had two pairs of pants. If you crossed Dutch, goodbye, you’d get whacked.”

“If you worked for him, he was very good-hearted,” he added. “These hoodlums and hoods, he had no use for them.”

While working for Schultz, Grauso claimed he “whacked … Mustache Petes, a couple of guys.” Along the way an assailant punched him in the nose with brass knuckles. He received a crippling stab wound to his leg. He asked Schultz for a few months off and returned to Connecticut. Months later, in 1935, Schultz was mortally wounded and others in his crew killed in a restaurant in New Jersey during a hit orchestrated by Louis “Lepke” Buchalter on orders from the Commission, made up of top American mafia leaders, including Luciano. The Commission had refused Schultz’s request to have Dewey killed, and when Schultz angrily vowed to kill Dewey himself, the leaders ordered the hit on Schultz. Grauso said Schultz had mentioned wanting to get rid of Dewey because the prosecutor was making a case against him.

Then one of Schultz’s men named Big Harry was gunned down. Grauso was warned not to return to New York.

“Things were hot. I knew they were after everybody. I was in line for a whack, ’cause anybody that represented the Dutch, everyone, they all got whacked. I got (news)papers to show in 1935, all of them that worked for Dutch got whacked.”

Grauso remained in Bridgeport, living at the Stratfield Hotel where he ran some card tables and loaned money to guests. He said he didn’t hurt those who missed loan payments, only increased their “vig,” or interest rate. He remained there until World War II. He was deemed unfit to enter the military during the war, joined the local draft board and worked as a driver for a military officer.

After the war, he essentially went straight. Law enforcement in Bridgeport had closed the brothels and numbers rackets. Grauso took a job working in the Sikorsky Aircraft factory where he remained for more than twenty years. But he wasn’t straight all the way. He admitted to running his own numbers racket inside the factory for his fellow employees.

“I had a set-up where no calls come in, only one call,” he said. “I had runners working for me.”

When federal agents raided the factory one year, “nineteen bookmakers they grabbed,” he said. “They didn’t touch me because I was in solid with the foremen inside, and the superintendent.”

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org