Eunice Carter: Key player in Luciano conviction

First African-American woman to earn law degree in New York helped put Mafia boss in prison

First in a series of profiles for Women’s History Month.

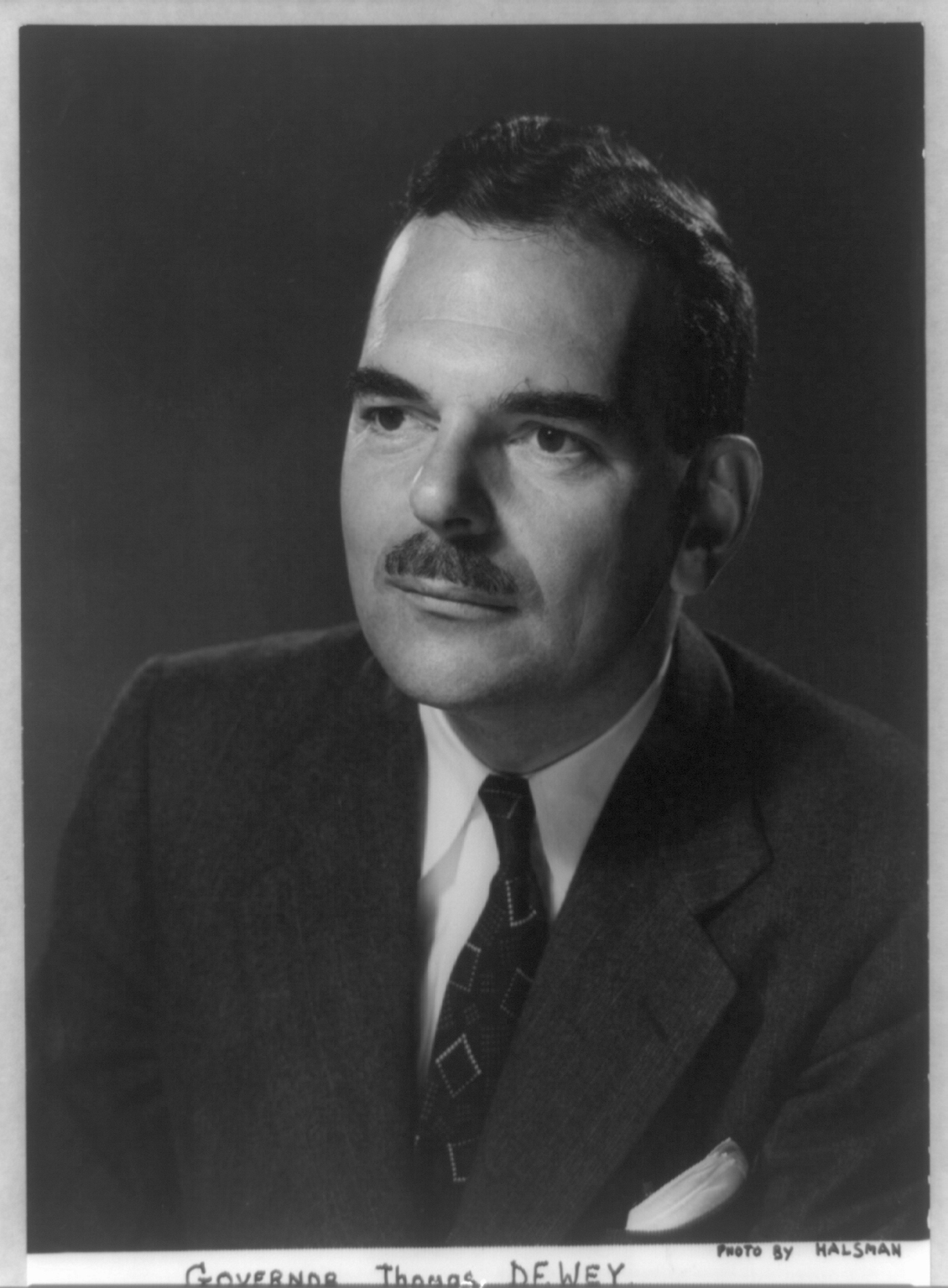

Eunice Carter made history throughout her life. But the crucial evidence she presented to New York State special prosecutor Thomas Dewey in the mid-1930s would result in one of the greatest prosecutions against organized crime in American history, sending Mafia “boss of bosses” Charles “Lucky” Luciano to a long stretch in prison.

Carter was born in 1899 in Atlanta. Her parents, who were social activists, instilled in her a sense of duty to serve. While making a living as a social worker in New York and New Jersey in the 1920s, she took classes at Fordham Law School and became the first African-American woman to receive a law degree there.

Her talents drew the attention of New York Mayor Fiorello La Guardia and newly appointed state special prosecutor Dewey in 1935. La Guardia and Dewey hired a large staff to fight organized crime and selected Carter to work in the predominately black area of Harlem. Carter thus became the first female African-American assistant district attorney in the state of New York. Her boss was Dewey, who while chief assistant U.S. attorney had won a conviction against New York bootlegger Waxey Gordon in 1933 and whose 1935 prosecution of mobster Dutch Schultz crippled Schultz’s operations.

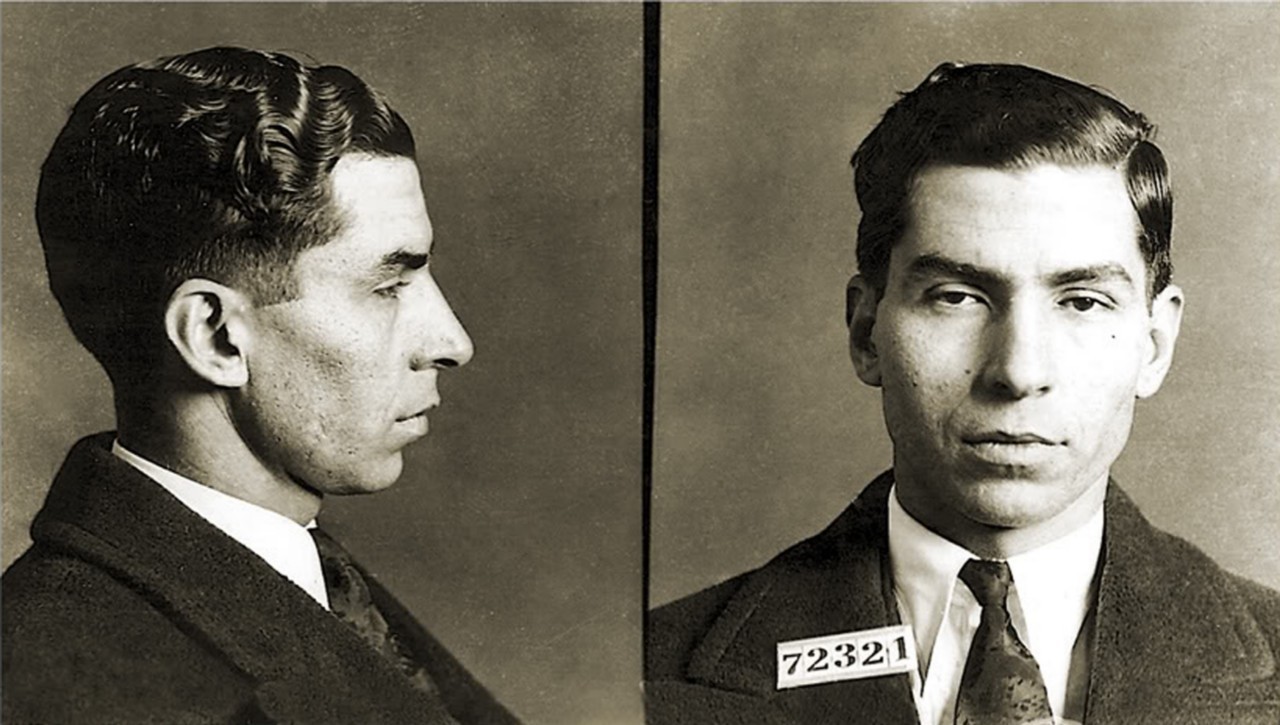

Carter’s destiny would be to catch an even bigger fish among the city’s Mob bosses – Lucky Luciano. Luciano rose to prominence as a bootlegger for the Sicilian Mafia during Prohibition. In 1931, he eliminated the old guard Sicilians through murder and intimidation. He then created America’s first national organized crime syndicate, the “Commission,” run by New York’s five Italian crime families and some top Jewish mobsters, such as Schulz and Luciano’s longtime friend, Meyer Lansky. By the mid-’30s, Luciano had his hands in multiple rackets, from drugs and illegal liquor to loan sharking, the numbers and prostitution, either by overseeing them or demanding payments from other operators.

Many of Carter’s cases as assistant district attorney in 1935 were brought against women charged with prostitution. As prosecutor, she noticed that some defendants were using the same bondsman and lawyers and told similar tales while trying to beat their raps. Carter reasoned that this cast of characters meant that hoodlums perhaps controlled New York’s prostitution as a racket. She approached Dewey and an investigation by his office confirmed her theory – racketeers were indeed deeply entrenched in illegal prostitution and collected 50 percent of their employees’ earnings.

Dewey ordered a raid of scores of brothels and arrested 100 illegal sex workers, several of whom agreed to testify about the Mob’s ties to the business. Luciano was charged with pandering on a large scale. His defense was that he was not directly linked to the brothels and was being railroaded by the prosecution. But Dewey, in a dramatic cross-examination of Luciano, asked how the rich mobster could afford an extravagant lifestyle on the $22,500 reported on his tax returns. The sensational trial ended in a guilty verdict and a sentence of 30 to 40 years for Luciano (who was paroled in 1946 and deported to Italy).

Luciano’s conviction, based on Carter’s discovery, was considered the most successful court action against organized crime in U.S. history. It put a dent in the Luciano syndicate’s illicit activities and political corruption. In 1937, Dewey, then New York’s City’s district attorney, assigned Carter to head his Special Sessions Bureau involving cases brought in municipal court, where she remained until 1945.

Carter thereafter worked as a private attorney, advised the United Nations on women’s rights issues, worked for the National Council of Negro Women and served as a national board member of the YMCA for many years. She died in 1970.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org