Undercover, under stress

Bob Delaney infiltrated the New Jersey Mob as an undercover state trooper for nearly three years. He regained his identity as an NBA referee

On September 28, 1977, 200 state troopers and FBI agents from all over New Jersey met at the armory in West Orange, launched a raid in groups of four and arrested 34 alleged members of the Bruno and Genovese crime families and various street criminals. The bust was the culmination of a nearly three-year undercover operation to collect evidence against mobsters engaging in labor racketeering, theft and selling stolen merchandise in northeastern New Jersey.

For state trooper Bob Delaney, that morning should have been one to revel in. He stood inside the armory and watched as members of the task force brought in the unwitting suspects who knew him by his undercover fake name, “Bobby Covert.” It was the end of the largest organized crime investigation ever in New Jersey. Federal prosecutors would use the evidence Delaney and his associates gathered to bring about 100 criminal cases.

But Delaney was in no mood to enjoy his success. Little did he know that he suffered from the effects of Post-Traumatic Stress Syndrome, an affliction not much appreciated in the 1970s but that his years working undercover undoubtedly caused. Delaney worked as a detective for the state police and then, to help free himself of his condition, turned to officiating basketball games, eventually serving 20 years as a referee for the National Basketball Association. Basketball, he would say, gave him his life back.

Delaney relates the full story of his nerve-racking stint working undercover with the dysfunctional whims of New Jersey hoodlums for almost three years, and his struggle as “Bobby Covert,” in his book Covert: My Years Infiltrating the Mob.

Delaney was an integral part of the 1975-77 undercover operation, known by only a few in law enforcement at the time as Project Alpha. To establish his cover, the state police told its own troopers that Delaney had been fired after he “went bad.” The story was that while a trooper he had killed someone in Florida. The tale spread into the New Jersey neighborhood where he grew up, embarrassing his parents who knew the truth but couldn’t talk about it.

The FBI and state police, using federal grant money, started a real trucking company to learn about the organized criminals selling and transporting stolen property and working labor union rackets near the New Jersey waterfront. The goal was to lure suspects and gather evidence to develop criminal charges. Delaney, only in his early 20s, as Bobby Covert wore a wire hidden in his jock strap and a 1970s reel-to-reel tape recorder on his abdomen to catch conversations he had with the suspects.

Hundreds of hours of taped conversations with mobsters and street criminals would be transcribed and considered as evidence by federal prosecutors. (In fact, Delaney and another trooper worked for weeks to transcribe the tapes themselves.) Authorities also installed a James Bond-style camera inside a stereo speaker in the trucking firm’s office that took pictures of each person coming in with a wall clock in the background to show what time it was.

The covert operation involved Delaney, another trooper and three FBI agents posing as trucking company employees. Delaney ran the company at first in a small location in Elizabeth, N.J. He started learning how the local Mob worked by hanging out at a nearby cocktail lounge called the Sting that served as a pay point for “shy” loans (from mob loansharks). In another bar, the JJ Tavern, the owner, after getting to know Delaney as “Bobby,” agreed to buy some stolen merchandise. Delaney’s group bought a truckload of ceramics and sold it to the bar owner for ten percent of its value. Then Delaney got to know two members of the Gambino crime family, who sold them some stolen state unemployment checks, all of it caught on tape.

The operation began to really bear fruit after the team turned a smart Mob associate named Pat Kelly into an informant. Authorities caught Kelly red-handed and offered him a deal – no prosecution and entry into the witness protection program for cooperation. Kelly joined and enthusiastically introduced the team to some of New Jersey’s top Mob leaders. They included Tino Fiumara (Genovese family crew boss), Jackie DiNorscio (Bruno family crew leader), John “Johnny D” DiGilio (Genovese crew leader) and Michael Coppola (Tino’s lieutenant). Kelly also presented Delaney to Joe Adonis Jr., son of the famous mobster Joe Adonis, an alleged participant in the slaying of Mafia boss Joseph Masseria at the behest of Charles “Lucky” Luciano in 1931.

Kelly convinced Delaney and the undercover team to move to a bigger trucking facility in Jersey City across the street from the park housing the Statue of Liberty. With Kelly as middleman, DiGilio agreed to use Delaney’s place as the “house” trucker of DiGilio’s Genovese-run frozen seafood business. Profits came in, and Delaney’s group had to kick back a twenty-five percent cut shared by Fiumara, DiGilio and DiNorscio. The Mob bosses tended to be greedy, petty and menacing, but sentimental about Mother’s Day. At one point, Delaney went to Florida with Kelly to confer about the trucking business with Bruno family members. Both Delaney and Kelly set up their hidden wires in the airline’s lavatory before the meeting.

All the while Delaney had to present a calm demeanor. He lied and defended himself in front of his mobster targets but was also careful not to arouse suspicion. The discovery of his wire would mean certain death. The pressure made him sweat and at times vomit after the meetings. He worked twelve to fifteen hours a day.

By 1977, the undercover operation had evidence that DiGilio engaged in racketeering with unions on the New Jersey waterfront. One wiseguy said in remarks picked up by Delaney’s wire that “Johnny is the union.” Soon, Fiumara informed them he would be taking over the trucking firm, but that “Bobby” could work for him. Finally, Delaney’s supervisor with state police announced they were shutting down the operation.

After the arrests from Project Alpha, Delaney was made a detective in the state police’s organized crime unit. But the emotional effects of being “Bobby” with hanging around with mobsters stayed with him. He was argumentative and cruel to his colleagues. One of his co-workers helped him realize his problem. A psychology professor he spoke with told Delaney “You’re in post-traumatic stress.”

“For me,” Delaney wrote, “Bobby Covert was a costume I was able to wear to enter a different side of life.”

“For me,” Delaney wrote, “Bobby Covert was a costume I was able to wear to enter a different side of life.”

Through Louis Freeh, the FBI’s field officer in New York (and future director of the FBI), Delaney met Joe Pistone, the famous undercover officer dubbed “Donnie Brasco” while blending in with the Bonnano crime group in New York from 1976 to 1981. “Bobby,” Pistone said. “this was our job. It was business – nothing more, nothing less.” Pistone became a close friend, assisting Delaney in recovering from his psychological wounds.

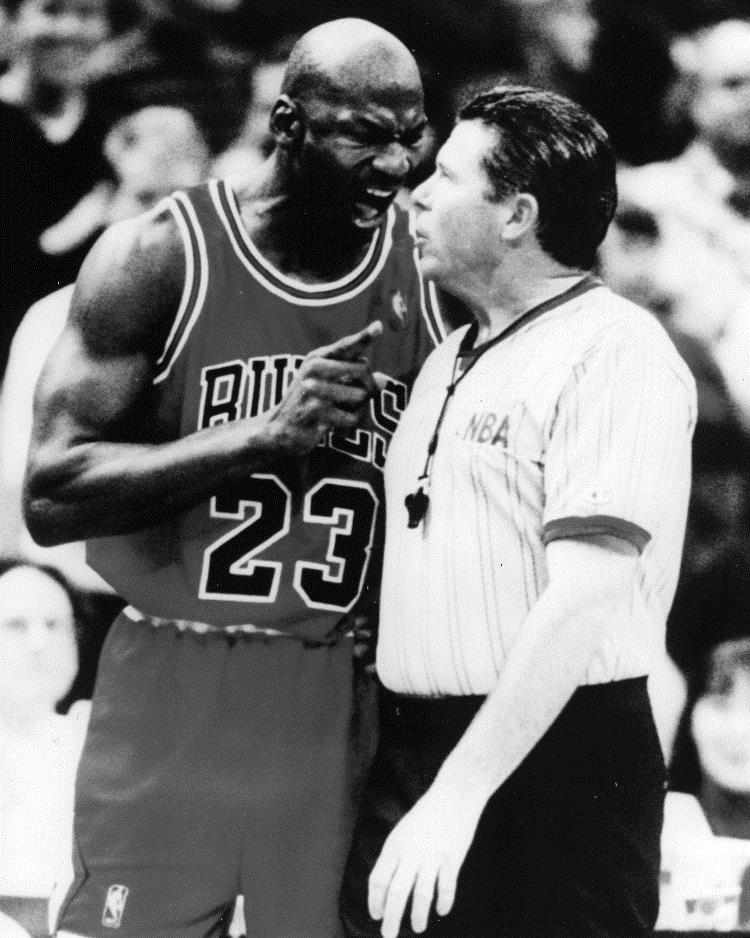

In the early 1980s, Delaney, a former player on the state police’s basketball team, decided to get back into that game as a referee. He began refereeing recreation league games, then progressed to high school, summer pro leagues with prospective NBA players, NBA preseason training games and the minor league pros, while also working full time as a teacher in the state police academy. Finally, he accepted an offer from the NBA to referee full time in 1987, a job he would hold for two decades.

Working for the NBA would be a catharsis for Delaney, a safe haven from the consequences of the dual life he led living with volatile criminals.

“I felt at home with the running, the adrenaline rush, the responsibility of officiating the game and enforcing the rules, allowing the athleticism of the players to unfold,” he wrote. “That was therapy for me, coming from the chaos I had lived through. This had structure and discipline, and with that came a sense of emotional security.”

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org