Fifty years ago, Jay Sarno opened Caesars Palace and changed the face of Las Vegas

Mob-tainted funds used to build iconic Strip resort

When hotel developer Jay Sarno unwrapped his innovative Caesars Palace hotel-casino for a prolonged grand opening party on August 5, 1966, the Ancient Rome-themed resort was like no other in Las Vegas. Four years in the making, Caesars would permanently transform practically everyone’s image of Las Vegas from a series of aging neon-lighted roadside attractions to new higher levels of everything — themed architecture, interior design, table service, split-level hotel suites, imported Italian sculpture, colorful fountains and toga-wearing cocktail waitresses. Over the past fifty years, Caesars Palace has left a lasting influence on how Las Vegas gambling houses are planned, built and operated.

But Sarno didn’t create Caesars out of whole cloth. The resort promoter extraordinaire had a few dress rehearsals along the way outside of Las Vegas. In January 1963, Sarno had been a Las Vegas resident for less than two years when he launched his latest project, the Cabana Motor Hotel out in Dallas, Texas, with partners that included the actress Doris Day. The Dallas Cabana had a Romanesque theme, a ten-floor L-shaped hotel tower, private cocktail lounge, separate male and female health clubs, 300 unique guest rooms adorned with drapes, walls and carpets colored in plum, turquoise, reds and olive hues, and fourteen split-level “petite suites.” Patrons were served drinks by waitresses dressed in Roman togas, including, for a while, a young Raquel Welch.

Sarno had spent $3.6 million developing the Dallas Cabana thanks to a loan from the Mob-connected Teamsters Union pension fund. Sarno was a tile contractor in Miami in the early 1950s when he met Teamsters officials Allen Dorfman and Jimmy Hoffa and clicked with them as friends. Sarno, with his partner and college buddy Stanley Mallin, installed tile in homes, first in Miami and later in Atlanta. Sarno, whose brother had worked in hotels, admired the then-hot European Modernist style of hotel architect Morris Lapidis, designer of Miami’s famous Fontainebleau. In the mid-’50s, Sarno met a prospective female employee, architect Jo Harris. He made advances, which Harris spurned. But he hired her anyway and she would turn into the executrix of his obsessive devotion to the interior designs of his hotels, including Caesars a decade later.

Sarno’s first lodging project was the Atlanta Cabana Motor Hotel, completed in 1958 with 200 rooms. It resembled Caesars in only a few ways, given the restraints of its location on Peachtree and Seventh streets in Atlanta’s midtown. One was the series of cement breeze blocks he used as a façade on the side of the four-floor hotel building to hide guest room windows from view. He installed a handful of Roman-style statues outside and a modest fountain beside the open-air swimming pool in view from the street. The lobby had two-story high windows, a grand starlight chandelier and a curving stairway. The guest rooms were done in bright colors. The Atlanta Cabana’s most impressive feature was its seven-story-high wall covered in light blue tile facing Peachtree.

The Atlanta Cabana is also famous for something else – it is said to have been the first project ever to receive a loan from the Teamsters’ Central States, Southeast, Southwest Area Pension Fund, via Dorfman with Hoffa’s blessing. The loan was for $1.8 million. Dorfman and Hoffa soon would busy themselves with other pension fund loans for many building projects – including Las Vegas hotels – for organized crime associates in the coming years. Hoffa often demanded a finder’s fee, or kickback, of about ten percent of the value of each loan.

Sarno, Mallin and Harris then moved to another city undergoing residential growth in the 1950s, Dallas. Sarno got acquainted with Clifford Heinz, a developer looking for investment capital to build hotels in Dallas and Palo Alto, California. In 1959, Heinz introduced Sarno to Jerome Rosenthal, a Hollywood entertainment lawyer who represented the actress Doris Day and her husband, theatrical agent Martin Melcher. A year later, Rosenthal convinced Day and Melcher to invest millions with Sarno and Heinz into their next hotel project, the Palo Alto Cabana. But even though Sarno and Heinz never contributed any equity, Rosenthal signed them on as full investment partners and he privately stole millions from Day and Melcher. (Rosenthal was later disbarred in California and lost a $3 million lawsuit brought by Day).

In 1962, Sarno and partners debuted the Palo Alto Cabana, considered the prelude to Caesars Palace. Photos of the front of the Palo Alto Cabana surely testify to that. The hotel was built well back from the street, fronted by a large imitation of the statue of the headless (Greek goddess) Winged Victory of Samothrace, a series of thirty-foot lighted fountains and a statue patterned after Michelangelo’s David, all between parallel driveways.

Sarno had made Las Vegas his home base for planning a hotel project the year before. An inveterate gambler who flew in and out of the city to gamble between business meetings, he felt existing Strip properties were raking in profits with so-so accommodations inferior to his Cabana motor inns. Nevada’s legal gambling also meant higher returns for a hotel with a casino attached to it. Sarno found a suitable building location on the Strip near Flamingo Road that he leased from future resort developer Kirk Kerkorian. Hoffa and Dorfman provided another pension fund loan of $10.6 million to back Caesars, plus a million or so more to help with bankrolling casino markers during its opening days.

With investor Nate Jacobson, partner Jerry Zarowitz, architect Melvin Grossman, and Joy Harris as his detail-focused designer, Sarno spent $24 million on Caesars. The end result was a Roman-themed, fourteen-story hotel with 680 rooms (covered by a breeze-block wall façade) set back 135 feet from the Strip. It had five sixty-foot-tall fountains out front, more imitation statues of Winged Victory of Samothrace and David and car lanes lined by Italian Cyprus trees. The hotel entrance, based on St. Peter’s Square in Rome, was enhanced by various bigger-than-life Roman-style statues of the Medici Venus, Canova Venus, Venus di Milo and Bacchus, fashioned by artisans in Italy. The columned front marquee was patterned after a ruin of Rome’s Forum.

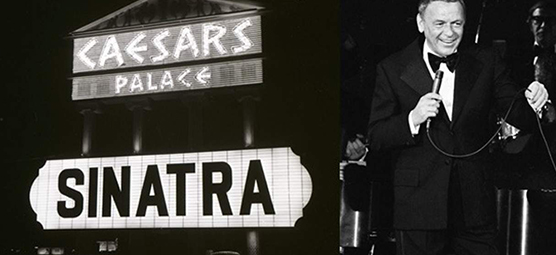

Inside, men dressed as Roman soldiers and women as Cleopatra served as greeters, and, as in Dallas, cocktail waitresses wore sexy toga dresses. In the Bacchanal Room gourmet restaurant, female waitresses in togas and bikini tops massaged the necks of male patrons. Hanging from the ceiling of the lobby was a 100-foot chandelier, created from 100,000 German-made crystals. The rear outdoor swimming pool, designed after a public pool in Pompeii, was built with 8,000 pieces of marble from an Italian quarry. Split-level suites afforded guests views of the Strip below. Singer Andy Williams opened Caesars’ 800-seat Circus Maximus showroom – intended to resemble the inside of Rome’s Coliseum – while the comic group the Ritz Brothers christened Nero’s Nook, a 250-seat lounge with a reflecting pool. Circus Maximus would be a venue for years to come for major stars, including Frank Sinatra, Sammy Davis Jr., Judy Garland, Woody Allen, Cher and Aretha Franklin.

Sarno was quoted as saying he named the resort “Caesars” without the apostrophe (to the constant confusion of many writers and editors) to mean he wanted everyone who entered to feel as though they were “a Caesar” and for his patrons “to leave the real world and enter a fantasy world.”

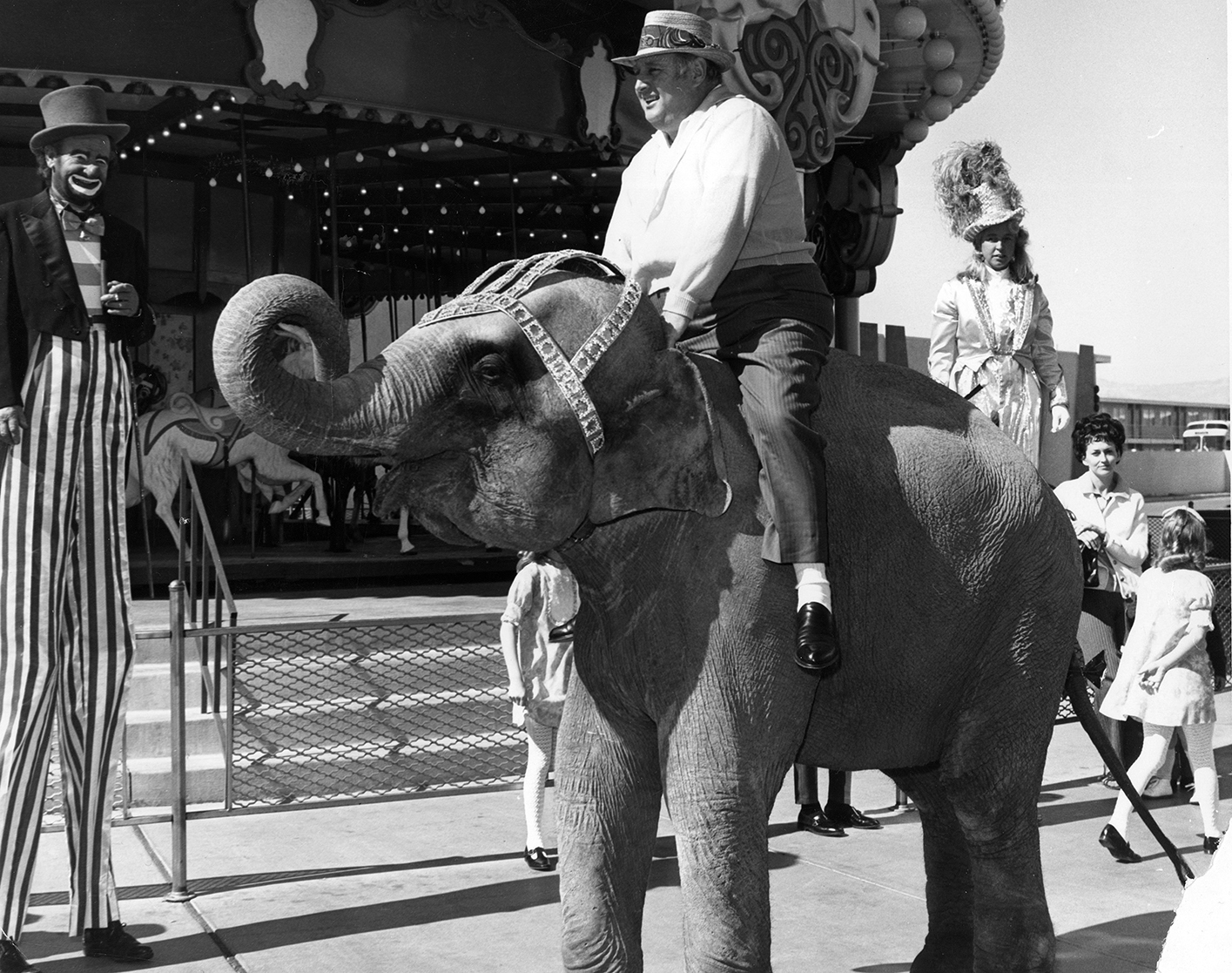

During the three-day, lavish grand opening party that hot summer week in August 1966, the partners spent $1 million on behalf of 1,400 attendees who milled in and out, consuming 50,000 glasses of champagne and hors d’oeuvres of Alaskan king crab, imported caviar and a couple of tons of filet mignon. Much more history would follow – daredevil Evel Knievel was almost killed in a failed attempt to jump over Caesars’ fountains on his motorcycle in 1967. Sarno, amid a federal investigation into Caesars’ finances, would sell the property in 1969 for $58 million to Clifford and Stewart Perlman, who secretly used Miami mobster Meyer Lansky as a hidden investor. Formula One car races were held in Las Vegas for several years starting in the late 1970s next to Caesars.

Many expensive renovations and additions followed, as have new owners. Today, Caesars, owned by Caesars Entertainment, has 4,000 rooms and is attached to an upscale shopping mall, the Forum Shops.

Most of Sarno’s Cabana motor inns bombed – Palo Alto’s was insolvent by 1968, Dallas’ went bankrupt in 1969. Sarno died in 1984 at age 62. But his Roman vision for Caesars, as kitschy and excessive as it was, was the right fit for Las Vegas, and it is still a classic half of a century later.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org