The rise of cyber-rackets

Devious uses of technology at core of modern organized crime, according to Europol report

International organized crime groups are using technology in ever-more-sophisticated ways, according to the Serious and Organized Threat Assessment 2017 report released by Europol, the law enforcement agency for the 28-member nation European Union.

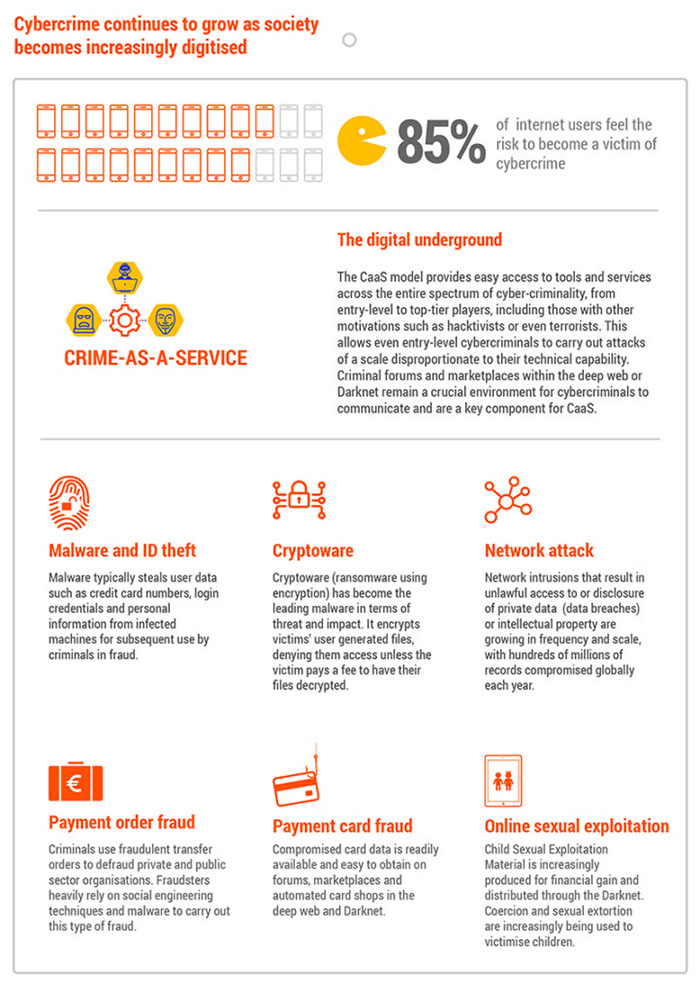

Crime groups are creating online marketplaces for criminal activity known as “Crime-as-a-Service,” or CaaS, providing veteran and newbie cybercriminals with tools to run their own criminal enterprises. They also are developing “cryptoware” that uses encryption to seize people’s computer files and forces them to pay a ransom to unlock them.

The Europol report, released February 28, is intended to supply the latest information on threats posed by transnational organized crime and terrorism for the EU, which has seen a surge in migrant smuggling and trafficking of humans by organized crime groups (OCGs) in recent years.

Europol estimates there are about 5,000 international OCGs representing 180 nationalities operating in the EU, with 30 to 40 percent functioning in a “loose network” and 20 percent that are “ad hoc,” existing for brief periods to complete special criminal ventures. About 75 percent of these OCGs have six or more members and the remaining 24 percent require as little as five or fewer people to operate. Seven of 10 of the EU’s OCGs tend to be active in three or more countries.

Driving organized crime these days are document fraud (from falsified transportation, customs and work contract documents to fake birth and marriage certificates and driver’s licenses), money laundering conspiracies and the online trade of illegal drugs, firearms, counterfeit currency and fake consumer products.

“Technology has had a fundamental and lasting impact on the nature of crime,” Europol states in the report. “Almost all types of illicit goods are now bought and sold via online platforms that offer the same ease of use and shopping experience as most legal online platforms.”

New methods of committing crimes through high technology is the most challenging trend for law enforcement in battling organized crime. One such technique is the CaaS model, in which OCGs enable both technology-savvy crooks and entry-level actors learning the trade “to operate their own criminal business without the need for the infrastructures maintained by ‘traditional’ OCGs.” CaaS includes digital service forums and marketplaces where cybercriminals may communicate over the “deep web” or “Darknet” – a cyberspace of hidden online rackets — about malware and organized trafficking of drugs, child sexual material, firearms and other goods. To cover their tracks from law enforcement, OCGs employ encryption when communicating online.

Money laundering, long a staple of organized crime, allows OCGs to shift funds from illegal activities to legitimate bank accounts, businesses or investments. Lately, OCGs have made covert online transactions using “cryptocurrencies” and payment methods that can be completed anonymously. These include online funds transferring platforms that are not as closely regulated as banks and other financial institutions. OCGs also depend on false and/or forged documents, invoices and identification papers to hide where their cash came from “to open bank accounts or to establish shell companies,” according to Europol.

“Money launderers provide services to both organized crime and terrorist organizations,” the agency reports.

Syndicates specializing in camouflaging money transfers offer their services to OCGs for fees ranging from 5 percent to 8 percent of transactions. In one case in 2015, Europol and officials in Spain ended a network that had laundered criminal profits from exploiting people for cheap labor, making counterfeit products and tax fraud in Spain and transferred the money to criminals in China. The network, which laundered nearly $368 million from the EU from 2009 to 2015, also extended money laundering services for a fee to criminals in other EU countries.

Modern cyber-rackets on the increase include identity theft, such as stealing credit card numbers, usernames and passwords and other personal information and offering it for sale in the Darknet marketplace; unleashing “cryptoware,” malware that hacks into a victims’ computer files, encrypts them so the victim cannot access them and then forces them to pay a fee to remove the encryption; network attacks to gain access to and steal private data or intellectual property, which affects hundreds of millions of business records each year; hacking into company computers to prepare fraudulent payment orders and having the money sent to the criminals; and the sale of child sexual materials obtained by exploiting and extorting children.

Another growing cybercrime is “card not present” (CNP) fraud, whereby criminals take advantage of transactions, typically online, involving a debit or credit card without the cardholder present by stealing their account information and making unauthorized charges. OCGs also make transactions on stolen cards, or “card present” fraud (CP).

The distribution and sale of illicit drugs is still the top moneymaker for international OCGs in the EU at $25.5 billion a year, with the market for synthetic drugs seen currently as the “most dynamic,” Europol reports. Of the EU OCGs, about 35 percent are active sellers of illegal drugs, and of those 75 percent engage in trafficking more than one drug and 65 percent combine drug sales with other criminal rackets.

The trafficking of drugs exists within a complex, global distribution network, and many drug-dealing OCGs offer customers their choice of a variety of illegal controlled substances – mostly cannabis, cocaine, heroin and synthetic drugs such as methamphetamine — a business known as “poly drug-trafficking,” the agency says. A growing sideline in the EU is the trafficking of synthetic drugs such as methamphetamine, amphetamine and a newer one with the long name of “3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine,” or MDMA, made from chemicals imported from China and converted to a marketable substance in the Netherlands and Belgium.

“More OCGs are involved in cocaine trafficking than any other criminal activity in the EU,” Europol reports. The EU’s illegal cocaine market is worth $6.1 billion a year.

Drug traffickers also are using technology to further their goals. One is hawking illicit drugs on the Darknet. Traffickers are also investing in cutting-edge technology to manufacture drugs, including for synthetics and indoor cannabis-growing operations. In the process they have devised new types of drugs – 419 new psychoactive substances have been discovered by EU officials in the last five years. Libya in northern Africa is becoming a top center for making and exporting cannabis resins smuggled into the EU.

OCGs are employing social media to manage the other major rackets that exploit people directly — migrant smuggling and the trafficking of human adults and children. Migrant smugglers, often working as vehicle drivers, use websites, even online ride-sharing platforms and peer-to-peer room rental sites, to route and house migrants seeking work or entry into the EU nations. They use voice-over-IP (VolP) and instant messaging from mobile phones to communicate with co-conspirators. These OCGs pass migrants through one network after another, frequently furnishing them with genuine passports with the photos of “lookalikes” to fool border authorities. In 2016, there were more than 510,000 illegal border crossings recorded by the EU.

Trafficking humans is a worldwide crime racket, and in the EU, the traditional human trade routes leading from Eastern Europe to Western Europe have been replaced by smuggling people into all EU countries. The “people” rackets include placing them in low-paid, exploitive jobs for business owners in industries with the least amount of regulation, including agriculture, cleaning, construction, fishing, retail and transportation. Other adults are exploited sexually by having to work as prostitutes in legitimate businesses such as hotels, nightclubs and massage parlors.

Traffickers also abuse children, especially underage girls, who are made to perform as sex objects in what Europol calls “Child Sexual Exploitation Material,” or CSEM, “which is traded on online platforms.” The materials include photos young girls are tricked into taking of themselves in a state of undress and the images are then distributed by criminals for profit.

Online technology also has enhanced the organized property crime racket for OCGs, which can more easily sell stolen materials – often mobile phones and other electronics — on the Darknet and other web marketplaces, use social media platforms to check when people leave their homes and are ripe for burglarizing, and click on mapping websites to case neighborhoods. OCGs are also increasing their proficiency in masking security measures in vehicles to steal specific models of cars requested by customers.

OCGs have used the unrest within Libya, Syria and Iraq to traffic in stolen cultural artifacts. The availability of cheap but effective drone technology is also being put to use to perform tasks for OCGs. And there is evidence that some terrorist organizations may be working with international organized crime groups to raise funds to bankroll terrorism campaigns.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org