A Midwestern Mob Murder Mystery

Wisconsin jukebox operator killed by Milwaukee mobsters didn’t go quietly

Amid heavy snowfall during the winter of 1963, FBI agents and sheriff’s deputies in Kenosha County, Wisconsin, worked together to solve the suspicious missing person case of Anthony Biernat, owner of a jukebox distribution company.

Biernat was last seen on the evening of January 7, when witnesses watched three men force him into a Ford sedan in the parking lot of Kenosha’s North Shore Line railroad station by Lake Michigan, about 60 miles north of Chicago.

Before he disappeared, Biernat, as owner of the Lakeside Music Company, harvested the coins used to play phonograph records inside 85 jukeboxes he owned in cocktail lounges, bowling alleys and other locations in Kenosha and Racine counties in Wisconsin and at a Navy boot camp in northern Illinois.

Two decades after his abduction, the Chicago Tribune described the Biernat case “as one of the Chicago-Milwaukee area’s most baffling mysteries.”

The kidnapping of the jukebox operator received considerable media coverage and raised suspicions that mobsters played a role. Wisconsin Governor John Reynolds publicly requested that the FBI join the Kenosha sheriff’s department’s investigation because state authorities were “relatively helpless in combating organized crime.” FBI agents arrived to determine if Biernat was kidnapped near the Wisconsin-Illinois state line and transported out of state, which would give them federal jurisdiction to enter the case.

Then an unidentified underworld source contacted Milwaukee police by phone, purporting to have information about the missing man. Police released the news to the media.

“If you want to find Biernat’s body, look in the basement of an empty house in an abandoned area in Kenosha County,” the person said. When the officer on the phone asked the caller to be more specific about the location, the source replied, “Well, you can be sure of one thing, it (the body) ain’t going to fly away.”

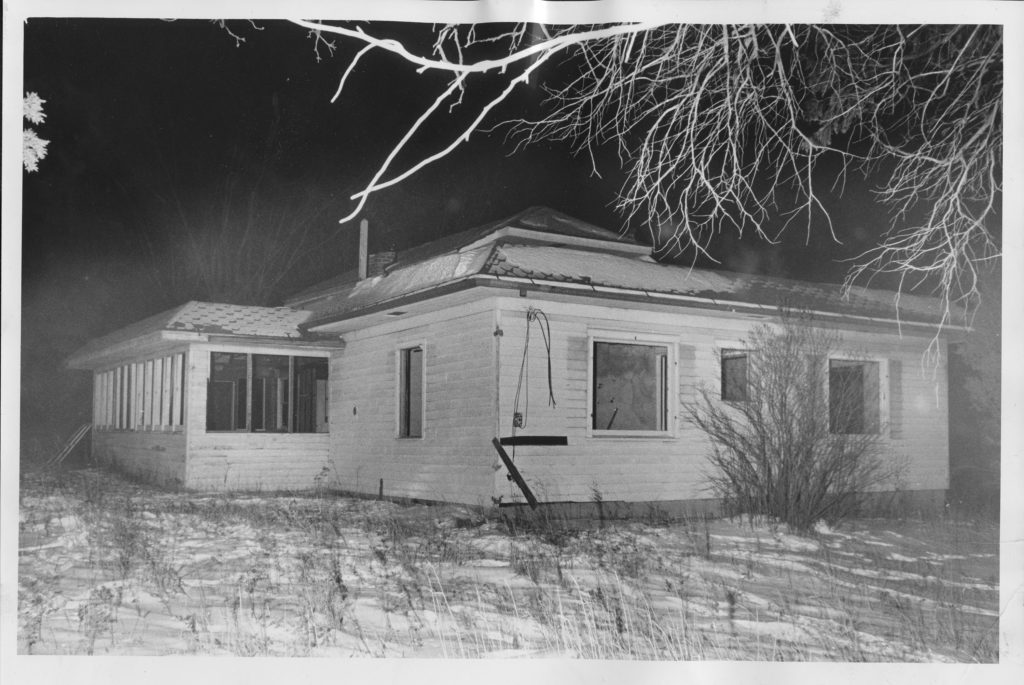

In Kenosha County, sheriff’s deputies interpreted the reference “ain’t going to fly away” to mean Biernat was somewhere at the abandoned Bong Air Force Base. The U.S. government started building the planned air base in rural Kenosha County in the mid-1950s, forcing nearby home owners to leave, but scrapped the project in 1959.

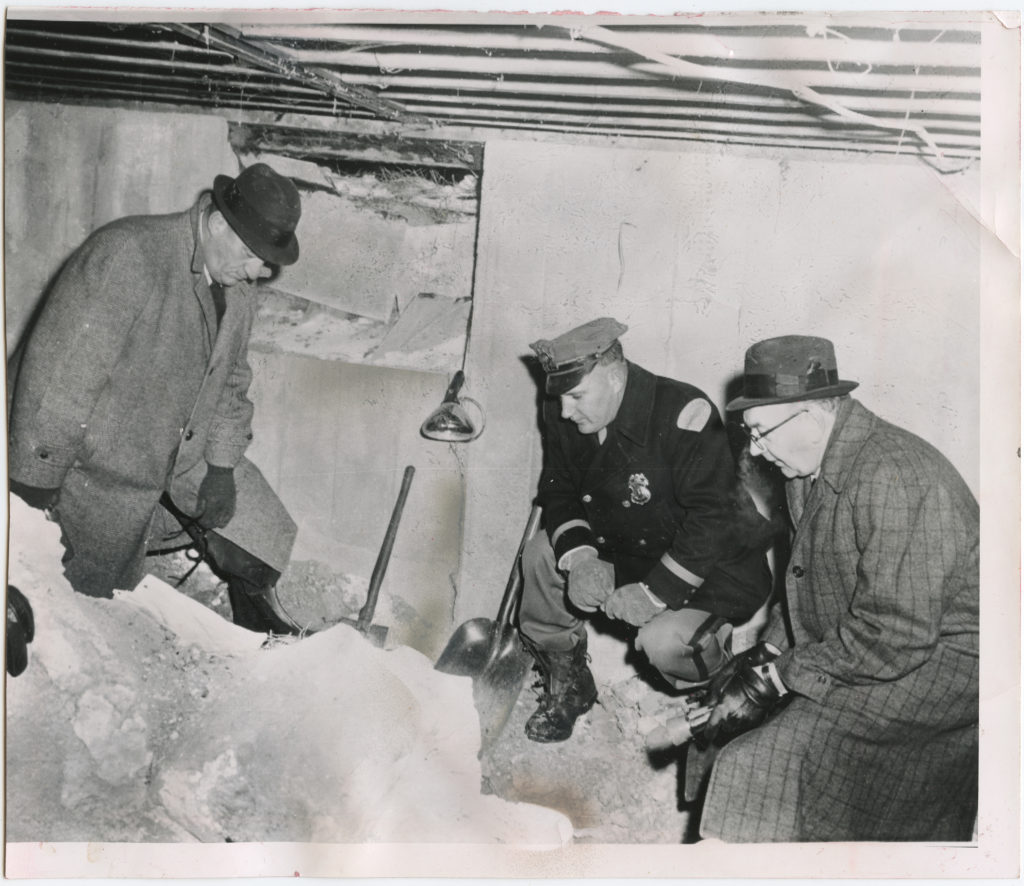

On January 28, deputies drove to the deserted property, about 20 miles outside the city of Kenosha, and found Biernat’s remains in the basement of a vacant farmhouse. The body lay tied up in a shallow grave and covered in lime by someone thinking it would promote decomposition, but the freezing cold weather prevented it. A coroner’s examination concluded Biernat died from three or four vicious blows to the back of his head with a sharp instrument.

The FBI and local officers, through confidential sources, heard that the Chicago Outfit had ordered the Milwaukee Mob, led by boss Frank Balistreri, to kill Biernat for refusing to enter into a “partnership” with Chicago in his jukebox company. The Chicago syndicate sought to muscle in on Biernat’s jukebox concession at the Great Lakes Training Center (the Navy boot camp) in North Chicago. The Mob also was said to have desired a share of Biernat’s take from coins in Wisconsin where the majority of his jukeboxes operated.

Biernat’s neighbors saw him as a respected citizen who nonetheless had ties to organized crime going back to the 1930s, when he serviced many of the illegal shot machines run by Chicago mobsters in northern Illinois. He later worked for a jukebox distributor in Kenosha and took over the machines when the previous owner entered military service in World War II. By 1962, Biernat’s business ranked sixth in revenue among the 12 coin-op businesses in the county. When he declined the Outfit’s demand for a cut of his business, Chicago put out a contract on him and contacted Milwaukee to do the job — or so the story went at the time.

Over the years, different accounts would emerge about what happened to Biernat. In one, underworld sources had heard that before the kidnapping, three men from the Milwaukee syndicate were dispatched to Kenosha to put a hit on Biernat for rebuffing the Mob’s demands. They hoped that if they secretly kidnapped him, police might not realize at first that he was missing. They selected the farmhouse basement as the gravesite as early as December 1962.

The scheme worked overall, but things didn’t go exactly as intended. The hoods found a man who knew Biernat and could point him out. They knew where Biernat bought his evening paper — the Kenosha train station. The four men waited together in the Ford sedan for Biernat to show. Seeing him drive into the station’s parking lot, their finger man identified the intended victim, then ran away. The three Mob torpedoes got out and grabbed Biernat. He put up quite a fight and bloodied one of the thugs. They shoved him into the Ford but noticed that some people were watching them. The mobsters, fearing they might be followed, grew nervous, placed a rope around Biernat’s neck and choked him to unconsciousness to keep him quiet (as it happened, none of the witnesses called police).

After they drove him to the farmhouse, Biernat awoke in the basement and again kicked and bruised the men. Biernat was struck repeatedly in the head with the butt of a gun, killing him. Still scared about being discovered, they abandoned a plan to seal the cellar with cinder blocks and cement. They covered the body with lime, draped only a piece of canvas over it and fled.

Authorities questioned the other 11 jukebox operators in Kenosha and none reported being contacted by organized crime. With law enforcement now keeping a watchful eye, it became too hot for the Mob to take over Beirnat’s machines.

Deputies had a body, a motive, but no suspects. The watch on Beirnat’s wrist had stopped at 12:20 a.m., leading them to believe he died after midnight the night he disappeared. One thousand people attended his funeral in Kenosha. No one was arrested, and who killed him remained a mystery.

Years later, another tale surfaced about the kidnapping and murder. In Kansas City, in 1968, before he died of a heart attack, former Mob figure Joseph “Joey G” Gurera confessed to investigators his involvement in Biernat’s murder with two others.

Gurera was identified as working for the Milwaukee crime family from February 1962 to March 1963. In 1960, a new group of Italian-Americans took control of the Milwaukee Mob. Seeking to expand their influence, the gangsters hired Gurera from Kansas City to “strong arm” gambling and other illegal operations to extort funds for the newly improved gang and force legitimate business in the Milwaukee area into partnerships. One such business was Biernat’s jukebox company.

The Mob demanded bookmakers and other criminals turn over one-third of their incomes. One illegal bookie in Milwaukee refused and the Mob marked him for dead. However, when the bookie heard about it, he changed his mind and gave in.

Gurera claimed that Milwaukee ordered him and two other henchmen to simply “work over” Biernat, intimidate him into doing business with the Milwaukee family, but not kill him. Biernat, however, had resisted them in front of witnesses. His violent defense in the basement with his worried captors led to the murder. One of the men hurt by Biernat required a doctor’s treatment. None of the six people interviewed by law enforcement who witnessed the abduction by the train station could identify any of the suspects. The paranoid gangsters didn’t have to kill Biernat after all.

The basement grave actually had been prepared for a different intended victim — the Milwaukee bookie who refused at first to give the Mob a piece of his bookmaking business — but it became Biernat’s.

Biernat’s departure attracted more heat than the Mob expected. When the FBI joined the probe, Milwaukee’s syndicate assigned a low-level Mob soldier to call local authorities to “leak” information about Biernat to direct them to the body, thus encouraging the FBI to leave since agents were investigating a possible interstate kidnapping, not murder. The leaker put the blame on the Chicago Outfit when in fact Milwaukee had been leaning on Biernat. The Milwaukee gang also feared FBI agents would get wind of its latest moves to expand in Milwaukee and southeastern Wisconsin.

More than 20 years after the slaying, the FBI came across a second possible suspect in Biernat’s murder. On November 30, 1984, more than 120 law enforcement officers, including police, 50 FBI agents and 11 IRS agents, raided a condominium building in Milwaukee to bust a Mob-related cocaine sales and extortion racket. Police recovered more than two kilograms of cocaine from the basement storage locker of Anthony Pipito, a soldier for Milwaukee boss Balistreri. Pipito had profited to the tune of $1.2 million in 1984 from selling cocaine. Federal prosecutors used evidence gathered from FBI wiretaps of Pipito’s phone conversations. Pipito, his wife, brother and son were among the dozen people arrested.

The raid occurred after Pipito, whose nickname was “Tony Pipe,” boasted to an FBI informant that he was one of the men who took part in the kidnapping and murder of Biernat. “I was the first (person) to hit Biernat,” Pipito said.

In an ironic twist, the federal judge who arraigned Pipito on multiple felony charges, John Reynolds, was the former governor of Wisconsin who had asked the FBI to investigate Biernat’s disappearance back in 1963. Reynolds ordered Pipito held without bail. Pipito’s wife was convicted of drug-related charges.

While Pipito was not charged in the Biernat murder, he was convicted in Milwaukee in 1985 of interstate sales of cocaine, conspiracy and engaging in a continuing criminal enterprise, known as the “kingpin” statute. Pipito was hit with 121 years in federal prison and made to serve at least 30 years. During his sentencing, he told the judge the feds had lied in court and dubbed the case against him “a fairy tale.” Before announcing the sentence, the trial judge, Thomas J. Curran, scolded Pipito: “You have a concern for other human beings that makes [former Uganda leader] Idi Amin look like an altar boy.”

Pipito died 26 years later in 2011. No one’s ever been arrested in Biernat’s more than half-century-old gangland murder, but at least names have been attached to two of the hoods who, by their own admission, took part.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org