The life and death of Joe Colombo

Mafia boss turned social activist was shot at a June 28, 1971, public rally in New York

Three rounds from an assassin’s gun all but silenced Joseph Colombo, one of the Mafia’s most publicly vocal bosses. Although he survived the June 28, 1971, attack, the wounds left Colombo almost completely paralyzed, and eventually proved mortal. He died seven years later from heart failure attributed to the lingering effects of his injuries.

“How can they make a guy like Colombo sit at the Commission?”

That question — posed by Frank Majuri, then underboss of New Jersey’s DeCavalacante crime family to his boss, Simone DeCavalacante — was captured on tape by the FBI and released publicly in 1969.

Joe Colombo didn’t fit the mold of a typical Mafia boss, at least in the minds of those who opposed him. Though he was a rising capo in the Profaci crime family, Colombo’s criminal record up to that point contained only two little infractions, a dollar fine for each.

His role in the hierarchy of the Magliocco crime family, however, took a dramatic leap when he defied orders from his boss, Joe Magliocco, to carry out a brazen plot against the heads of two other New York families. Tasked with killing Gaetano “Tommy” Lucchese and Carlo Gambino, Colombo instead went to the intended targets and tipped them off to the conspiracy.

The story goes that Magliocco, who stepped in as boss when Joe Profaci died in 1962, already had problems with a renegade faction of the former Profaci family – the Gallo brothers: Albert “Kid Blast” Gallo, Larry Gallo and Joseph “Crazy Joe” Gallo. Both Magliocco and Colombo were kidnapped and held for ransom at one point by the Gallos.

Colombo secretly joined forces with Joseph Bonanno, head of his own eponymously named family. The scheme, thought to be a power play devised by Bonanno, was designed to seize control of the remnants of the Profaci family and to place Bonanno in the top seat among the crime family leaders representing the national La Cosa Nostra, known as the Commission. Interestingly, both Bonanno and Magliocco were ordered to appear before the Commission after the plot was revealed, during which the latter admitted ordering the hit. Magliocco’s life was spared but not without prompt demotion (he died of a heart attack a few months later). Bonanno was a no-show, but the Commission members knew he was likely the mastermind and they planned to deal with “Joe Bananas” later. For Colombo, the Commission meeting resulted in a career promotion.

By early 1970, Colombo’s name made the newspapers on a fairly regular basis – as both a “Mafia boss” and as the mouthpiece of a new organization he founded called the Italian-American Civil Rights League. The organization came out of the gate with a vengeance, seeking to remove the stigma of the “Mafia” and “La Cosa Nostra” from Italians. Colombo’s group accused the FBI of hiring informants to give false testimony and manufacturing conspiracies against Italian-Americans. Upon its inception, the IACRL issued statements to the press explaining its mission, including: “The purpose of the League is similar to that of B’nai B’rith’s Anti-Defamation League. We want to be another and a very strong civil rights group. We’re not going to limit our help to any group. Anyone who wants our assistance will get it.”

Although Colombo held no specific position in the IACRL (its president, Natale Marcone, was the actual “head”), he became a frequent and very vocal speaker at the marches and “unity events” that followed its creation. Among their activities, a throng of IACRL members converged outside the FBI office after Colombo’s son was arrested in April 1970 on arguably “questionable” charges related to melting silver coins (he was later acquitted). The group rallied in support of Joe Colombo when he and 13 others were indicted on charges ranging from usury to criminal contempt.

“That’s the new trend,” an unnamed FBI agent commented to the press. “Everybody, even the Mafia, is demonstrating now.”

Colombo consistently claimed to be in “real estate,” and regularly talked up the charitable contributions made by his organization. He also consistently denied accusations of Mob involvement and often gave reporters statements condemning law enforcement’s portrayal of him as a member of the Mafia.

“If I am as big and as bad as they say I am, I will demand that good be done,” he said.

Perhaps to the dismay of federal authorities, Colombo’s Italian-American Civil Rights League grew quickly into a force to be reckoned with, even gaining itself a benefit concert from Frank Sinatra. An estimated 100,000 people attended the group’s first “Unity Day” rally held in New York’s iconic Columbus Circle in the summer of 1970. In less than a year’s time, Colombo’s organization had about 40,000 dues-paying members across several states and recorded some impressive victories, including a Justice Department order to the FBI and other agencies to not use the terms “Mafia” and “Cosa Nostra” in their reports and convincing producers of the movie The Godfather and TV show The FBI to refrain from using both expressions in their scripts.

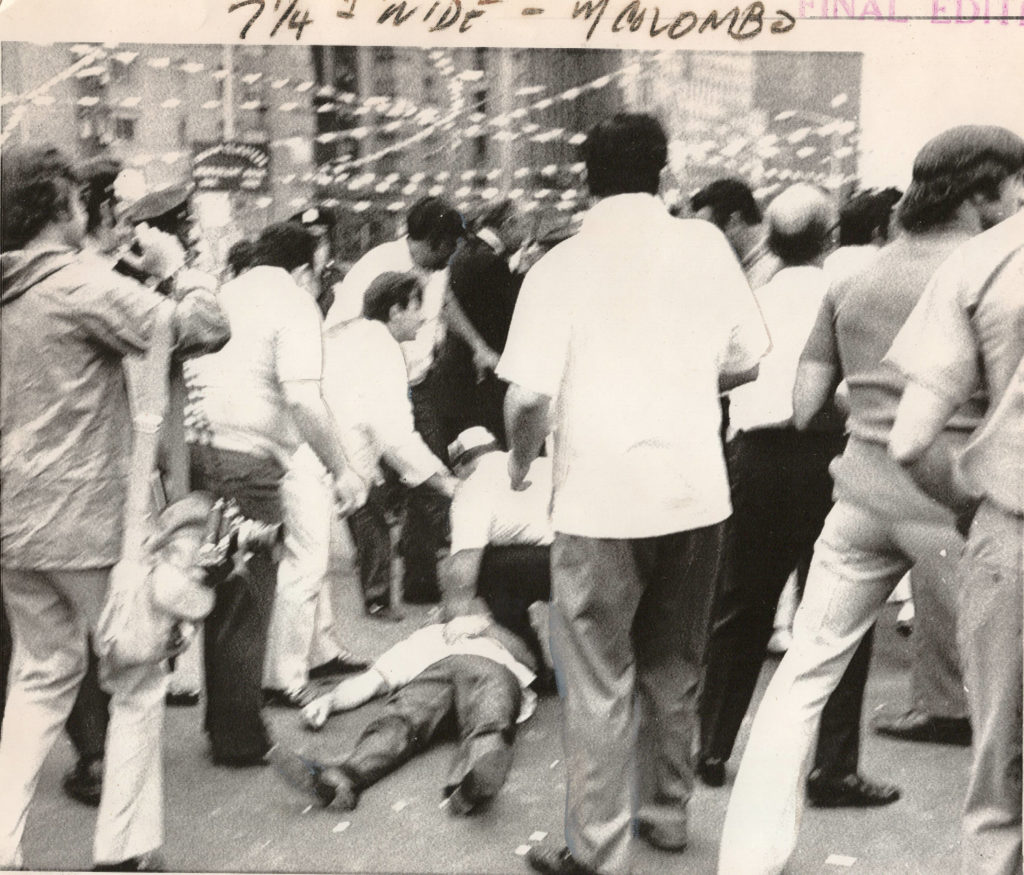

And then all hell broke loose on Monday, June 28, 1971.

Smiling and unaware of looming danger, the 48-year-old crime family boss cheerily greeted guests who arrived for the big Unity Day festival at Columbus Circle. A man brandishing both press credentials and a revolver approached Colombo, and from point-blank range fired three shots into Colombo’s head. The bloody scene turned even more chaotic. “They got Colombo!” someone in the crowd cried out. “A colored guy did it!” yelled another. Within seconds, police officers and attendees descended upon the gunman, but while the tussle ensued and general melee within the large crowd created further confusion, another series of shots rang out. An unknown third party felled the suspected shooter of Joe Colombo and was never apprehended despite heavy police presence at the rally.

Paramedics resuscitated Colombo as they rushed him to Roosevelt Hospital in critical condition. Surgeons quickly began the task of removing the bullets, a slug from the mid-brain and one from the neck, during the five-hour operation. Notwithstanding the grim odds of a “less than 50-50” chance of survival, the comatose Colombo’s condition had slightly improved by the next morning, as he was able to breath on his own and move his left arm. Meanwhile, investigators recovered several handguns from the bloody scene at Columbus Circle, and quickly identified the assailant, who was pronounced dead on arrival: 25-year-old Jerome A. Johnson, a resident of New Jersey and an individual police described as a “gun buff” and “an admirer of Hitler.”

Carl Cecora, a rally leader, recounted to The New York Times that he’d seen a woman talking to Colombo. “She was with a guy, a colored guy taking pictures, and they asked Joe to pose and everyone to spread out, and before you know it, the shooting started.”

Witness accounts of what happened thereafter varied, though, and ultimately proved inconclusive as to who fired the fatal rounds into Jerome Johnson. A UPI photographer positioned near the scene told authorities there was a “brief exchange of gunfire between police and the assailant” that dropped the latter to the pavement “bleeding from the back.” Police, however, stated they had no conclusive information regarding the mysterious other shooter. Almost immediately, conspiracy theories started circulating, with some blaming a government plot, while others felt it was the Mob’s doing. Investigators largely leaned toward a “gang war” theory, specifically a connection to Mob malcontent “Crazy Joe” Gallo (who was shot and killed at a restaurant the following year). The mysteries of why Johnson shot Colombo and who silenced Johnson are still debated to this day.

Joe Colombo lived out most of the next seven years at his Brooklyn home, still comatose and paralyzed. In early May 1978, with his health deteriorating rapidly, Colombo was taken to St. Luke’s Hospital in Newburgh, suffering from “intra-cerebral problems.” Colombo, age 54, passed away two weeks later on May 22, 1978. Hospital staff announced “cardiac arrest” as the official cause of death, “brought on by his injury seven years ago.”

Christian Cipollini is an organized crime historian and the award-winning author and creator of the comic book series LUCKY, based on the true story of Charles “Lucky” Luciano. Go to www.ganglandlegends.com.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org