While progress is evident, global wildlife trafficking remains a major criminal racket

China, Vietnam pass laws to curb wildlife crime as Interpol’s month-long raid in 92 countries identifies 1,400 alleged smugglers

The worldwide illegal trade in living and dead wildlife has expanded in recent years to rank among the four largest criminal rackets. Organized networks are exploiting animals and plants for profit to feckless customers as exotic pets, restaurant “delicacies,” jewelry, perfume, rawhide accessories and quack medicine.

However, there has been significant progress in the fight against wildlife trafficking just in the past couple of years. Two countries in Asia with long histories in the illegal trade passed laws banning some of the most egregious types of wildlife trafficking. In addition, in May, a group of international police agencies headed by Interpol put a major dent in the global criminal racket with coordinated raids in 92 countries that identified 1,400 suspects.

No one can estimate precisely the value of illegally traded wildlife, but it has grown rapidly in only the past several years. The United Nations in 2014 estimated profits from this black market at $7 billion to $23 billion each year, placing it fourth behind human, firearms and drug trafficking in earnings reaped by transnational criminal rackets. In 2016, the U.N. said the value had increased by 26 percent and projected it would continue to grow annually by 5 to 7 percent. Not included in the estimate is the huge market for illegal fishing products – $11 billion to $24 billion a year.

The Washington, D.C.-based research group Defenders of Wildlife, which advocates against the illegal wildlife industry, reported in 2014 that the world’s traffickers were selling about 350 million animals and plants each year.

Some of the most trafficked living things are also the planet’s most vulnerable species. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) has issued guidelines – adopted by 183 countries – on international trade that do not threaten the survival of wildlife. Among the most trafficked animals and plants listed as protected by CITES are elephants, rhinoceros, marine and fresh water turtles, sharks, ornamental fish, pangolins, great apes, parrots, raptors, helmeted hornbill, big cats, rosewood, agarwood and sandalwood.

One of the latest hotbeds for wildlife trafficking is the Southeast Asian nation of Laos, considered a leading conduit for smuggling ivory (from the tusks of elephants) and for “tiger farms” where tigers are kept in captivity for slaughter and body parts. Tiger bone, for example, used in so-called traditional medicine – for export to Thailand, China and Vietnam. A kind of wine made from tiger parts sells for as much as $250 a bottle. While bribery is rampant in the Laotian government, authorities there did arrest Vixay Keosavang, the country’s trafficking boss, nicknamed the “Pablo Escobar of the wildlife trade.”

Meanwhile, the war on rhinos in South Africa continues, as poachers killed more than 1,000 of them in 2017 (up from only 13 in 2007) just to saw off and sell the animals’ distinctive horns. Demand for rhino horn is high in China, where it is ground down into power form and claimed as a cure for fever and hangover, even though (like pangolin scales) it is made of keratin with no known medicinal value. Rhino powder has become popular among China’s new rich as a “party drug” to sniff like cocaine and an “alcoholic drink” for millionaires seeking to impress their peers.

In Mexico, in the Gulf of California, fisherman are poaching totobaba fish, which are protected by Mexican law, for the “swim bladder” inside the fish. In China, the wealthy will pay $20,000 for just a kilogram of the dried bladders, seen as a pricey delicacy for soups and for promoting better circulation, skin and fertility. A deadly byproduct of fishing for totobaba is the endangered vaquita, a small dolphin caught in the same gill nets and left to die. Only about 20 vaquita remain in the wild and extinction is likely by 2020.

Traffickers even pursue the Arctic narwhal whale, located mainly in Canada, Norway and Russia, for the mammal’s unique spear-like tusks that grow up to 16 feet long. In Japan, fans of traditional medicine believe that ground narwhal tusk can relieve general pain, fevers, measles and venereal disease, and will fork over as much as $929 for only 100 grams of the stuff. In 2013, a drive by U.S. and Canadian officials called Operation Longtooth, against trafficking in narwhal tusks in the United States, ended with the arrest of a man with 250 tusks.

Wildlife trafficking has shifted from isolated acts by small bands of poachers to a major profit stream for transnational syndicates, according to William Woody, chief of law enforcement for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“Today, it is the purview of international criminal cartels that are well structured, highly organized, and capable of illegally moving large commercial volumes of wildlife and wildlife products,” Woody told the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Foreign Affairs in 2016. “What was once a local or regional problem has become a global crisis, as increasingly sophisticated, violent, and ruthless criminal organizations have branched into wildlife trafficking,” he said. “Organized criminal enterprises are a growing threat to wildlife, the world’s economy, and global security.”

As cited by the U.N., leading the list of illegally trafficked flora and fauna, based on government seizures at shipping ports and elsewhere throughout the world, is rosewood, a rare and protected red-colored wood from trees in Asia that poachers cut for producers of expensive carved furniture. Next is ivory from elephants, used for decorations and jewelry; big cat and reptile skins for fashion items; agarwood, a wood resin used in incense and perfumes; pangolin, rhinoceros horn and bear bile for medicine, food and tonics; parrots, freshwater turtles and great apes as pets, zoo animals and for breeding; and caviar and marine turtles for food.

The United States is among the top consumers of illegally traded wildlife, along with China, Vietnam and other nations in Southeast Asia. While the legal U.S. trade in wildlife (i.e., pets, seafood and leather) is about $6 billion a year, illegal shipments are worth around $2 billion annually, according to the General Accounting Office.

The top 10 shipments of illegal wildlife products confiscated by U.S. authorities from 2007 to 2016 were coral, crocodile, conch, deer, python, sea turtle, mollusks, ginseng, clam and seahorse, the GAO said. Latin America is one of the largest points of origin for smuggling wildlife products into the United States, such as queen conch sea snails, sea turtles and iguanas, and belts, wallets and boots made from caiman and crocodile skins. The leading nations sending illegal wildlife to the U.S. are Mexico, China and Canada. Other wildlife trafficked to America include sea horses, clams, cobras and rattlesnakes. Still, government wildlife inspectors, overwhelmed by the millions of tons of cargo from airplanes and ocean freight, know that many other illegal wildlife products make it through.

For years, two countries that served as targets for criticism for their lack of action in preventing the smuggling of protected wildlife have been China and Vietnam. However, both nations have finally made serious efforts toward cracking down.

China, long the world’s most profligate importer and consumer of ivory, formally banned the trade as of January 1, 2018. How well China enforces the prohibition remains an open question, but the action is good news. Due to ivory smuggling, the African elephant population fell 62 percent from 2007 to 2017, while in China the price for ivory surged.

Meanwhile, Vietnam – long a major consumer of dubious “traditional medicines” produced from animal parts – in 2016 made poaching, trading and consuming illegal wildlife a crime carrying penalties of up to 15 years in prison and a $660,000 fine.

Both China and Vietnam launched national public awareness campaigns for their recent wildlife trafficking laws. Demand for traditional medicine has risen in recent years as middle classes in the two countries enjoy greater prosperity and purchasing power. The nations have had an unquenchable thirst for animal parts, specifically pangolin scales, rhino horns and tiger bones sold by prescribers to believers in traditional medicines based largely on ancient folklore.

In China, traditional medicine goes back 3,000 years, with the philosophy of vital energy, or “Qi,” of the whole body. Users think traditional medicines from animal parts restore the balance of Yin and Yang, or positive and negative energy in the body. Chinese men especially desire tiger parts, from bones to the nose, tail, eyes and penis, for enhancing sexual energy, despite China’s ban in 1993 on trading tiger bone. Most experts estimate there are only about 3,200 tigers left worldwide.

Vietnam’s efforts to discourage further use of pangolin scales is more far-reaching in that professors of traditional medicine have officially debunked claims that powder from the ground scales – that are, like rhino horn, made of keratin, the same as human fingernails – have medicinal value.

The pangolin, an ant-eating mammal about the size of a house cat, is the most trafficked wild animal in the world, with demand in Vietnam, China and other Asian counties with ancient histories predating modern science. Worldwide, poachers caught and killed an estimated one million pangolins in Asia and Africa over the last decade, and the four Asian species of the animal appear headed for extinction. In Vietnam alone, authorities confiscated 54 tons of pangolins and 14 tons of scales during that time.

Some restaurants in Asia serve pangolin meat, including fetuses from the animal, as an expensive delicacy sold at $1,000 each. The scales may go for $200 a kilogram. Sellers of traditional medicine in Asia tout pangolin scales as a treatment for maladies ranging from cancer and diabetes to asthma, open sores and blocked milk ducts in women who are nursing. Practitioners also believe the scales increase energy and vitality in men. In Africa, traditional medicine practitioners make the same dubious claims that the animal’s bones, eyes and other parts can treat rheumatism, stroke, menstrual pain, even kleptomania.

A turning point in Vietnam came last year when leading doctors of traditional medicine at Ho Chi Minh City’s University of Medicine announced publicly that there is no evidence that pangolin scales are effective as medicine and that the nation’s schools of traditional medicine would instruct students to prescribe other remedies.

Still more progress against global wildlife trafficking came recently on the enforcement front. In May, the international police agency Interpol led a month-long crackdown, code-named Operation Thunderstorm, which exposed the extent of the illegal trade in living and dead wildlife.

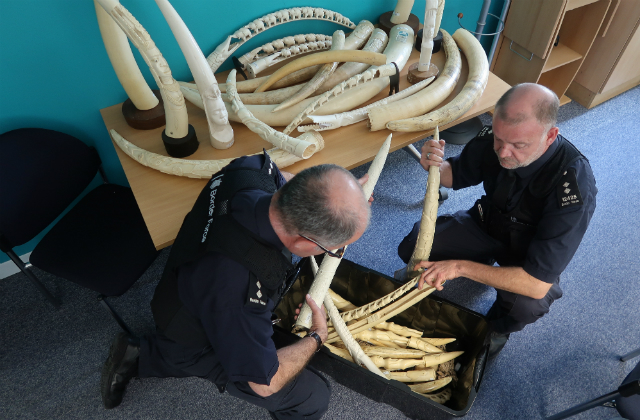

Interpol oversaw more than 1,900 seizures within 92 nations resulting in the confiscation of an astonishing 43 tons of wild animal meat, such as bear, crocodile, elephant, whale and zebra. Other captured items included eight tons of pangolin scales, 1.3 tons of ivory, 18 tons of Asian eel meat, the carcasses of seven bears, including two polar bears, and several tons of illegally cut wood and timber. The live animals saved totaled 27,000 reptiles (such as 10,000 snakes, 9,500 turtles and 860 alligators/crocodiles), about 4,000 birds (pelicans, ostriches, parrots and owls), 48 live primates and 14 big cats (tiger, lion, leopard and jaguar).

The operation, involving law enforcement officers in Europe, Africa, Asia, South America, Middle East, the United Kingdom, United States and Canada, ended with the identification of 1,400 suspects, notably two airline attendants arrested in Los Angeles allegedly attempting to hide live spotted turtles – a protected species – in their baggage in order to sell them after landing in Asia.

The Customs and Border Patrol worked with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to conduct inspections at the U.S.-Mexico border in Arizona and the U.S-Canadian border in Alaska. At New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport, authorities stopped a passenger from Guyana trying to smuggle live songbirds inside hair curlers in a piece of luggage. At the Port of New York, wildlife inspectors caught people attempting to sneak in live scorpions and giant African land snails. The border patrol seized a container of 1,800 partial sea turtle shells that are valued on the black market.

Officers in the international operation gathered intelligence from known centers of wildlife trafficking on international borders, at airports and inside parks with protected wildlife. They employed sniffer dogs and X-ray scanners to catch smugglers using boats, cars and trucks to transport illicit products.

The Interpol Wildlife Crime Working Group planned the effort, joined by World Customs Organization and the International Consortium on Combating Wildlife Crime, which includes CITES, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the World Bank. It was the second in Interpol’s “Thunder” series, following last year’s Operation Thunderbird multinational anti-wildlife enforcement campaign.

“By revealing how wildlife trafficking groups use the same routes as criminals involved in other crime areas – often hand in hand with tax evasion, corruption, money laundering and violent crime – Operation Thunderstorm sends a clear message to wildlife criminals that the world’s law enforcement community is homing in on them,” Interpol Secretary General Jürgen Stock stated in a news release.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org