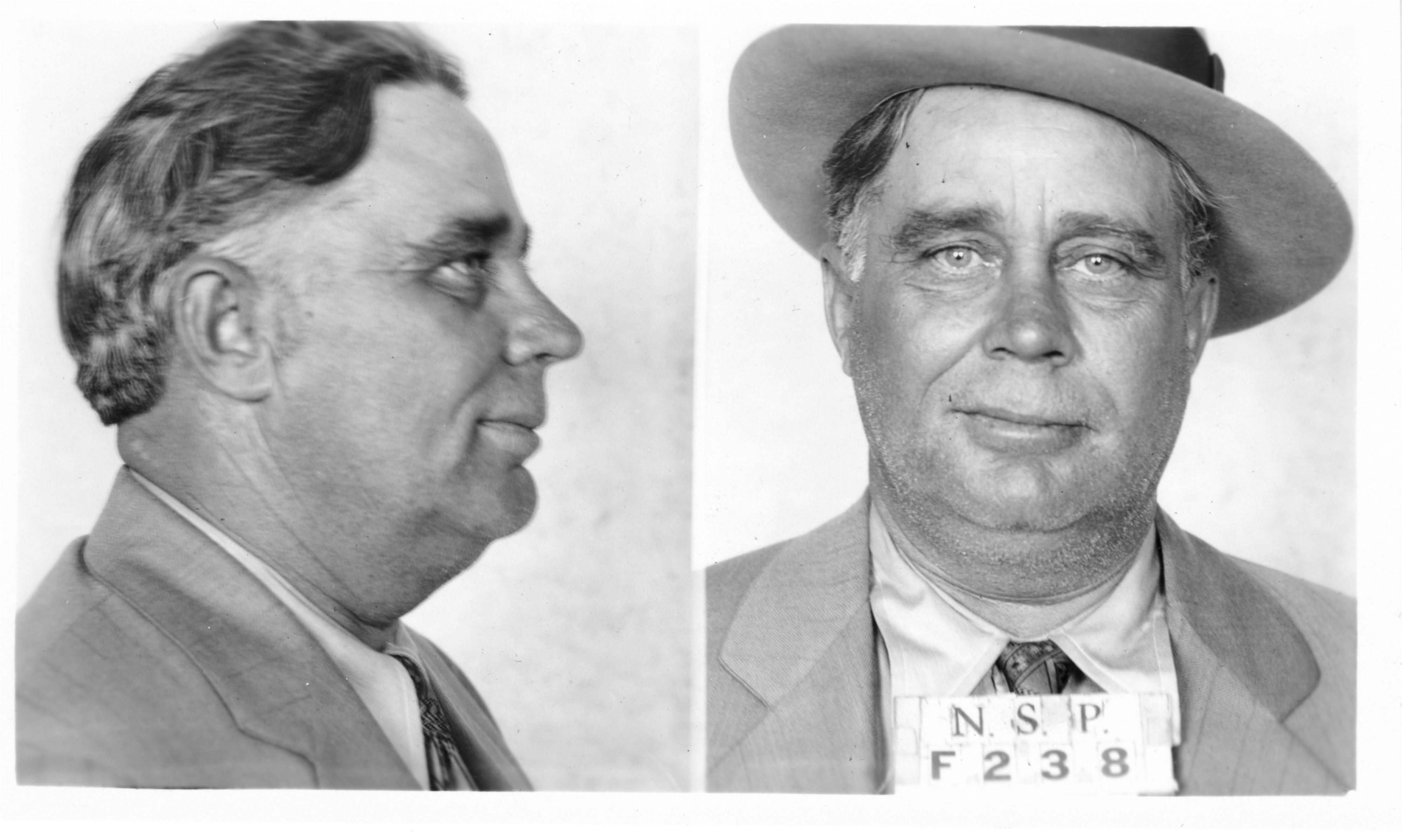

The first mobster in Las Vegas: Part 2

Federal law enforcement takes aim at Las Vegas crime kingpin Jim Ferguson

Second of three parts

The year 1928 initially looked good from Jim Ferguson’s standpoint. The “King of the Tenderloin” in Las Vegas had a strong working relationship with Mayor Fred Hesse and Police Commissioner Roy Neagle, as well as Police Chief Spud Lake. Ferguson also had a tight grip on the bootleggers in the Las Vegas area. What’s more, his wife oversaw the local brothels.

However, six weeks into the new year, his position as Las Vegas’s gangster-in-chief started to crumble. Federal officials, unhappy with the inaction of local law enforcement, for the first time in two years staged a massive surprise raid. Just after 5 p.m. on February 6, 1928, Prohibition enforcement agents stormed Las Vegas’ so-called “booze halls.”

Undercover agents had been in Las Vegas for a week and said they were able to buy liquor all over town. The “Prohis” busted and closed a dozen places within Ferguson’s territory. One of the largest raids took place at the Arizona Club, across the street from his home. Not only were Ferguson’s liquor joints shut down, but federal agents arrested many members of his motley gang.

Mayor Hesse was quick to come to the rescue. Working all the next day, he sought to transfer the cases from federal jurisdiction to the city court. Hesse offered the U.S. government a deal. If it would move the cases to local jurisdiction, the city would pay for the entire cost of the raid. After considerable negotiations, the feds agreed.

Forty-eight hours after the raids, the city court held a special hearing. Suddenly, cash started flowing in from the “tenderloin” to influence the process. A published report at the time stated: “Hundred-dollar bills stumbled over each other in their haste to get into the city treasury.”

By nightfall of February 8, 1928, the city treasury found itself with an additional $4,800. Minus the $650 it would send to the federal government for the cost of the raid, the city netted $4,150, almost certainly originating from Ferguson’s operation.

The payoffs led to a number of Ferguson’s liquor dens reopening their doors. Still, a couple of Ferguson’s retail bootlegging outlets stayed closed, and those who ran others worried about another federal raid.

By the spring of 1928, Ferguson’s crime fiefdom was back in full operation. But not for long. It soon would collapse again. It began with the tragic shooting death of an 8-year-old boy. The child was the son of a Las Vegas bootlegger, Charles Bradshaw, who refused to pay Ferguson’s protection fee.

About 7:30 p.m. on Saturday, June 16, 1928, Bradshaw and his family were traveling east on Charleston Boulevard. Heading west was Police Chief Spud Lake, his wife and a “special” police officer named Henry Deadrich, whom Lake had deputized 24 hours earlier. Lake recognized Bradshaw as the driver of the oncoming car, turned his car around and gave chase. Crossing the railroad tracks, the two vehicles turned south on Main Street.

Lake said he turned on the siren in his car, and when Bradshaw refused to stop, he ordered Deadrich to shoot at the tires of the bootlegger’s car. Deadrich fired several shots. The last bullet shattered the back window, hitting 8-year-old Sheridan Bradshaw, who was in the back seat.

Shortly after midnight, with a “soft-nosed”.45 slug still in his head, the boy died.

The child’s death would force the resignation of Police Chief Lake. The chief would, in addition to facing murder charges, along with Mayor Hesse and a city commissioner, face federal bootlegging conspiracy charges.

Ferguson would separately face, for the first time, the more serious charges of bootlegging on the federal level. This time the mayor would not be able to bury the case in the city courts.

Police arrested Deadrich, and word spread through the community. At the time of his arrest, Deadrich admitted being the one who fired shots at Bradshaw’s car. Police placed Deadrich, who had been in ill health and under medical care, in a jail cell along with a nurse.

Within hours of the boy’s death, county officials scheduled an inquest at the Clark County Courthouse and quickly empaneled jurors. At 11:05 p.m. that Sunday, the panel of local citizens issued its ruling: “Deceased met his death as result of gunshot wound inflicted by a weapon in hands of Henry Deadrich, the pistol being fired accidentally.”

Police Chief Lake, who was driving the car at the time of the shooting, testified at the inquest, after which he also was arrested and taken to jail.

In less than 30 minutes, just before midnight, police brought Lake and Deadrich back to court for their arraignments. They pleaded not guilty and a judge set bail at $5,000 for each. They were released on bond an hour later, about 1 a.m.

Mayor Hesse and County Commissioner James Cashman put up the money to bail out Lake and Deadrich.

The next day, June 18, after meeting with Hesse and Police Commissioner Roy Neagle, Lake resigned. He said he did so to “relieve the city administration of any possible embarrassment.” Hours after Lake’s resignation, Clark County District Attorney Harley Harmon said he planned to charge the two men with first-degree murder.

The charge confused many in the community. Some thought the DA was playing favorites, knowing how unlikely it would be for a local jury to convict the men of first-degree murder. Some residents believed a more appropriate charge was involuntary manslaughter.

Harmon disagreed, saying he was “convinced that a serious state of affairs exists in Las Vegas, of which this tragedy is but a climax.”

The DA admitted he was a longtime friend of the two defendants, but he added, “I have no intention of laying down on this case. To my mind it’s one of the most important that’s ever faced our community and I intended to see it through.”

A local judge overruled Harmon, saying it appeared that “the crime of murder was not committed, but the crime of manslaughter has been committed,” and he ordered the “defendants be held for trial for involuntary manslaughter.”

With the two former police officers awaiting trial, exactly one month after the death of Bradshaw’s son federal agents raided Ferguson’s home.

Bradshaw, who claimed Hesse, Lake and Deadrich shared the blame for his son’s death, had turned his attention to Ferguson. He reported to federal agents the extent of Ferguson’s operation and where the mobster kept his stash of bootlegged liquor.

At 9 a.m. on July 16, 1928, federal agents, armed with a search warrant, knocked on the door to Ferguson’s home across the street from Block 16. He was still sleeping when they arrived. Going through a partially concealed trap door, the officers entered the basement and found bottles and kegs of liquor, “enough,” a newspaper reported, to supply the “needs of the city for a considerable time.”

In addition to more than 200 gallons of whiskey, agents recovered bottles and a large quantity of phony labels, reading that the contents were “bonded goods” approved by “His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales.”

The raid resulted in the largest seizure of illegal liquor in the city’s history. Federal agents arrested Ferguson. A judge arraigned him on multiple counts of violating the federal Volstead Act prohibiting the sale of liquor, and the judge set his bail at $10,000.

Unable to post bond this time, Ferguson remained in jail until authorities transported him to Northern Nevada to appear at the federal courthouse in Carson City. On August 4, 1928, Ferguson pleaded guilty to the federal liquor charges and paid a $500 fine. It earned him his release, and he returned to Las Vegas.

While not a direct party to the trial, Ferguson’s name was front and center in the trial for the killing of 8-year-old Sheridan Bradshaw. When Lake and Deadrich went on trial in the youth’s death in September 1928, they faced an all-male jury.

During the week-long trial, Charles Bradshaw testified that he was with his wife and three children driving east on Charleston Boulevard not far from the railroad tracks. Also on the road were Police Chief Lake, his wife and a man Lake had hours before appointed as a special officer.

“They was going one way and I was going the other,” Bradshaw said. “I was going 20 to 25 miles an hour.”

“Did you know who they were?” the district attorney asked.

“No,” Bradshaw said. “I didn’t know them.”

Bradshaw quoted his wife as saying of the people in the car, “There goes a jolly crowd. I guess they are going to the dance.” He said there was “a woman and two men, laughing and cutting up in the car.”

“I did not know they were turned around until they dashed up and my wife said, ‘Look out, somebody is going to run into you.’”

“What was the occasion for his shooting?” the prosecutor asked.

“Don’t ask me,” Bradshaw responded.

He testified that the only shot he heard “hit the glass behind me.”

“When was it you first knew the boy was hurt?”

“I had my Panama hat,” Bradshaw said, “and told my little boy to hold it, and my wife said she seen blood on my white Panama hat and she began to cry and holler, ‘My baby’s shot.’”

Bradshaw said that after taking the boy to the hospital, doctors told the family there was no hope for survival.

When officers searched Bradshaw’s car, they found several gallons of homemade bootleg whiskey inside.

Former Police Chief Lake took the stand. District Attorney Harmon asked him if he knew who the occupants of the car were before ordering the special officer to fire shots at it. “I didn’t know for sure, but thought it was Mr. Bradshaw and his family,” Lake said.

“Figuring there were children and women, you directed him to shoot at the tires?” the prosecutor asked.

Lake said that was true. “To shoot at the tires and stop the car.”

The special officer fired three shots, he testified.

The DA asked him if he had a warrant for Bradshaw’s arrest on the misdemeanor bootlegging charge. Lake said he did not.

Bradshaw testified that he had been paying Ferguson $50 a month “for protection” for five months. During that time, he said local police officers never molested Ferguson. However, after he stopped paying Ferguson, he had been arrested three times.

At the end of the trial, the jury deliberated for only 30 minutes before bringing back a verdict of not guilty on the manslaughter charges. After speaking with jury members, the Las Vegas Review reported the jury “felt Bradshaw was entirely wrong in carrying his family along on a bootlegging expedition and that the responsibly for what happened was traceable to his own willful disregard for the safety of his wife and children.”

Harmon said it was wrong for police to shoot at a vehicle to make a misdemeanor arrest, adding that the “promiscuous shooting by officers for petty offenses must be discouraged if human life is to be protected.”

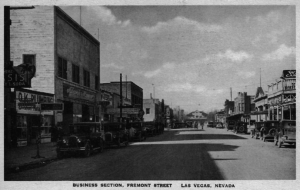

In late December 1928, many Las Vegans felt the need for a celebratory drink when President Calvin Coolidge signed the long-awaited legislation to build Hoover Dam. With construction of the $100 million dam project now authorized, the town filled with entrepreneurs, real estate speculators and fast-buck artists who wanted to get in on the ground floor of the impending local economic boom. Weeks later, the Los Angeles Times sent one of its reporters, Harry Carr, to find out what was going on in Las Vegas.

“Scattered around town are possibly 12 to 20 saloons,” Carr wrote. “They are running wide open, just as in pre-Prohibition days. The ‘barkeep’ swabs the beer off the top of the bar as in the days of the dear, dead past. There is also a restricted and licensed red-light district. The Delilahs who inhabit this district complain that they are perishing of starvation and that the real estate boom has brought only cheapskates.”

In March 1929, a month after the Times published its story, Las Vegas was once again front-page news. In a surprise move, the U.S. marshal arrived in Las Vegas with a handful of arrest warrants. The marshal and his deputies once again arrested Ferguson.

Meanwhile, a federal grand jury was hearing testimony about the inner workings of Ferguson’s bootlegging business and his relationship with Las Vegas officials. The grand jury continued to meet through the early part of 1929 before handing out a series of indictments.

But this time the feds also took Mayor Hesse, Commissioner Neagle and former Police Chief Lake into custody. All told, the federal government charged 20 people with conspiracy to violate federal liquor laws.

Some pleaded guilty and paid a fine. Others such as Hesse, Neagle and Lake pleaded not guilty and posted bail.

Once again, Ferguson was unable to raise money for bail and took a repeat trip to Carson City to await trial.

Robert Stoldal, a longtime television news executive in Las Vegas, is a Las Vegas historian and member of The Mob Museum’s Board of Directors.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org