World War I played key role in passage of Prohibition

A century ago, anti-German sentiment and war rationing paved the way for the 18th Amendment

In January 1919, Albert Von Tinzler and Edward Laska published “The Alcoholic Blues,” a song describing the feelings of a World War I veteran as he considers the newly ratified Prohibition Amendment. In its second verse, the narrator laments, “I wouldn’t mind to live forever in a trench, if my daily thirst they only let me quench. But not with Bevo or ginger ale, I want the real stuff by the pail.”

This song, though perhaps overdramatic, illustrates the “wet” reaction to Prohibition. And its connection to World War I helps demonstrate one of the final events that helped to pass the 18th Amendment.

November 11, 2018, marks the 100th anniversary of Armistice Day, the official end of World War I. On this day, an armistice was signed between the Allies and Germany in Compiegne, France. World War I began in Europe in 1914, but the United States did not formally declare war until April 6, 1917. Because of America’s late entry into the global conflict, its effects are often downplayed. But historians can trace the Bolshevik Revolution, the Great Depression, World War II and the Holocaust back to the war. Its impact on the temperance movement paved the way for 13 dry years and the rise of the Mob.

By the time the United States entered World War I, temperance advocates had passed a number of state prohibition laws. They had implored politicians to think about the children harmed by the effects of alcohol abuse. They had articulated the physical, mental and spiritual benefits of temperance. But those arguments alone were not enough to accomplish the dry agenda at the national level. World War I provided the final solid push toward a constitutional amendment by making temperance synonymous with patriotism, thrift and prudence.

The temperance movement began in the early 1800s. Some of its first supporters were Protestant clergymen, medical doctors and women. They came together to fight high levels of alcohol consumption across the United States. Alcohol was not regulated in the 19th century the way it is today. So when you purchased a bottle of whiskey, what might have been 80 proof one month might be 180 proof the next.

Distilling spirits was a big business in early America. Farmers across the country soon realized it was more profitable to turn crops such as wheat and corn into whiskey and bourbon before sending it to market. Distilled spirits were plentiful and relatively cheap. By the 1820s, whiskey sold for 25 cents per gallon — cheaper than coffee, tea or milk. Surplus crops only grew as Americans pushed farther into the frontier. By the turn of the 20th century, it was easier than ever to get a cheap drink. Brewery-sponsored saloons multiplied across the country.

The drinking culture that developed was nothing short of excessive. In 1830, the average American drank seven gallons of liquor a year, more than three times today’s average. That works out to more than a bottle and a half of standard 80-proof liquor per person per week. And it is worth noting that this figure is based on the drinking habits of every person age 15 and older. Essentially everyone in America was drinking — teenagers, ministers, even pregnant women. And temperance reformers drew connections between high levels of alcohol consumption and higher rates of poverty, illness and domestic abuse.

Early temperance reformers were more focused on rehabilitating the individual than pushing policy change. But after the Civil War, temperance societies began pushing for state-level prohibition. By the time America entered World War I, 21 states were dry. Arguments for prohibition were already well-established. And they fit nicely within the goals of the Progressive Era, a period of social and political reform from the 1890s to the 1920s. Progressives believed political action should improve the conditions associated with industrialization, urbanization and government corruption. Many progressive causes, such as child labor reform, direct democracy and women’s suffrage, did create a more equitable, safer and less corrupt society. But many progressive causes, including eugenics and prohibition, are unpalatable today.

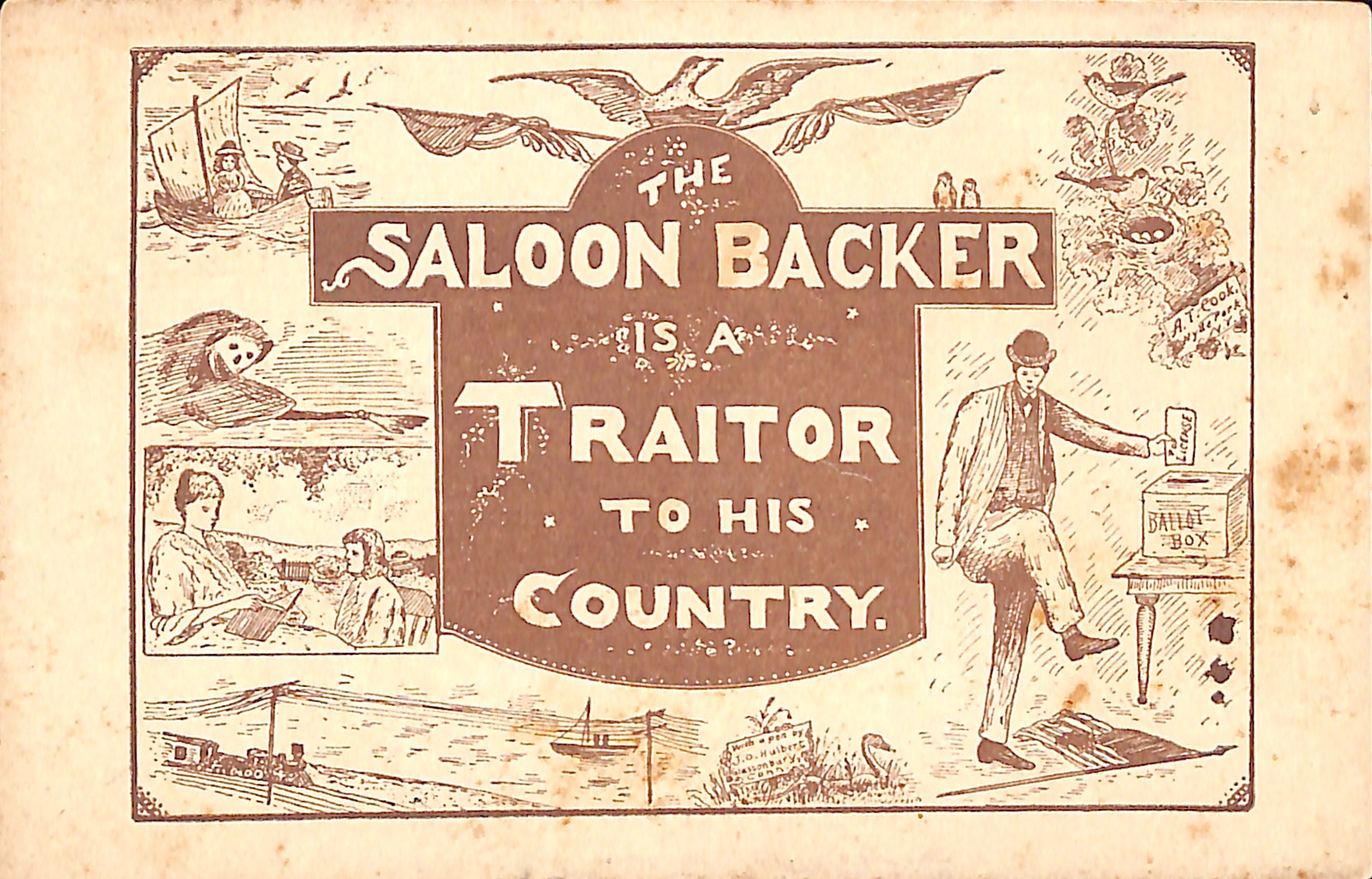

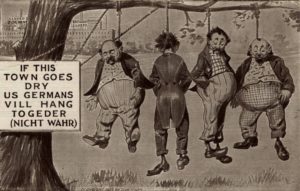

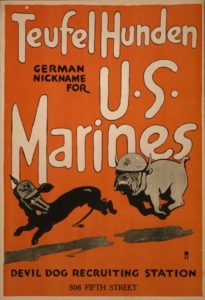

Prohibition advocates in the early 20th century also relied on racist and xenophobic rhetoric. By connecting alcohol production (and consumption) with German, Irish, Catholic and Jewish Americans, temperance was framed as an “us vs. them” problem. World War I allowed prohibitionists to manipulate growing anti-German sentiment. A large percentage of breweries were owned and operated by German Americans. They argued that every dollar put into the brewers’ pockets, and every bushel of grain diverted to a brewery, aided the German war effort.

In the 1910 U.S. Census, more than nine million respondents spoke German as their first language — 10 percent of the national population. When war broke out in Europe in 1914, support for Germany was generally tolerated in the United States, though the government’s early position was neutral. But by 1917, it became publicly unacceptable to support the German cause. Anti-German sentiment grew so strong that sauerkraut was renamed “liberty cabbage.” German music and books were banned in public festivals. Between 1917 and the 1920s, 14 states banned German language instruction in schools. Even dachshunds were not spared. Numerous newspapers tell stories of the German breed being shot or stoned to death – or, more peacefully, renamed wiener dogs. Beer essentially became unpatriotic.

It fit a convenient narrative to accuse German brewers of subverting the Allied powers. Before, brewers were accused of breaking up families. Now, they were portrayed as breaking apart the very fabric of American society. They had the power to intoxicate and incapacitate American soldiers. Former Wisconsin Lieutenant Governor John Strange summarized this fear in a February 1918 speech:

“We have German enemies across the water. We have German enemies in this country, too. And the worst of all our German enemies, the most treacherous, the most menacing, are Pabst, Schlitz, Blatz and Miller. They are the worst Germans who ever afflicted themselves on a long-suffering people.”

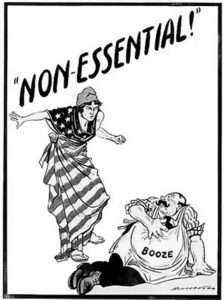

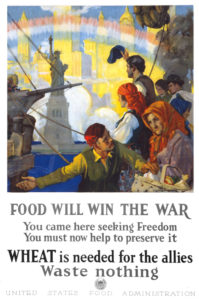

A more practical argument for Prohibition developed out of wartime rationing. Across the Western world, countries established measures meant to ensure soldiers received proper rations. Food production in Europe was down, and citizens in the United States and Canada worked to pick up the slack. In March 1917, the U.S. National War Garden Commission was established to assist Americans with the cultivation of small “war gardens.” In August 1917, the Food and Fuel Control Act outlawed the use of any grains or foodstuffs for producing distilled spirits. This emergency wartime measure was set to expire at the end of World War I. But it was one of many measures that prepared the American public for an eventual ban on liquor.

In December 1917, President Woodrow Wilson signed a proclamation forbidding brewers from brewing beverages with more than 2.75 percent alcohol by volume. Dry zones were established around military camps. The Selective Service Act forbade the sale of liquor to men in uniform.

Other countries established similar wartime measures. Russia passed a law in 1914 prohibiting the manufacture and sale of vodka for the duration of the war. Sweden established a rationing system in 1917. In 1915, Great Britain passed a “no treating order,” which stipulated that no one may pay for, or “treat,” another person’s bar tab. Britain also increased taxes on liquor and limited the hours in which bars could operate. But the United

States took it even further.

In December 1917, less than a year after formally entering the war, the tide officially turned for Prohibition. Years before, Alabama Representative Richmond Hobson had introduced the “Hobson resolution,” which would become the 18th Amendment. His resolution prohibited the manufacture, sale, transport and import of all intoxicating beverages in the United States. It won a majority of votes during its first consideration in 1914 but was short the two-thirds majority required to send it to the states for review.

But by December 1917, Congress’ opinion of temperance had changed. The proposal for the 18th Amendment was submitted to the states on December 22. By January 1919, ratification by two-thirds of the 48 states was complete.

World War I was the final rallying cry for the temperance cause, but it had other effects on Prohibition and its 13 years of enforcement as well. Cultural changes during World War I had a broader impact on the following decade. Some of the conditions now attributed to the World War II in fact began during World War I. World War I strengthened the power of the federal government. Large nation-states formed across Europe and the Americas, paving the way for more powerful, centralized governments.

Just as their granddaughters did in the 1940s, many single women also entered the workforce during World War I. These working women were the first generation to receive paychecks outside the home. Their financial freedom during wartime was then expanded upon by the carefree, independent “flappers” who emerged in the Roaring Twenties.

The most famous firearm of the era, the Thompson submachine gun, was originally developed for use in World War I. Its inventor, General John T. Thompson, envisioned a semiautomatic rifle that would be effective in the trenches and could ultimately replace bolt-action service rifles. Unfortunately for General Thompson, the war ended before his prototypes could be used in battle. This led to a re-evaluation of its uses.

During the 1920s, the Tommy gun was marketed for both law enforcement and civilian use and fell into the hands of Prohibition-era bootleggers and mobsters. And so it was that a gun developed for the war became a tool to enforce — or subvert — the American war on liquor that would wage across the country for the next 13 years.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org