Gus Greenbaum, Las Vegas casino operator for the Mob, and his wife were murdered 60 years ago this week

Vicious slayings in their Phoenix home had look of Mob hit but were never solved

After nightfall on December 2, 1958, Bess Greenbaum, wife of Las Vegas casino boss Gus Greenbaum, drove from their Phoenix house to take their housemaid, Pearl Ray, home after work, as usual. After dropping off Pearl, Bess headed back to the large residence at 1115 W. Monte Vista Road, across from the sprawling Encanto Park. The roundtrip to Pearl’s place on 15th Avenue in Bess’s white 1957 Cadillac was only about four miles, perhaps 12 minutes of driving time.

Just who (one or more assailants) entered the Greenbaum home before Bess returned that night remains a mystery to this day. The viciousness of the beating and knifing deaths of Gus Greenbaum, 65, and Bess Greenbaum, 64, had the distinct appearance of a mob hit.

Pearl suffered from shock after discovering Bess’s body the next day. Following treatment in a hospital, she provided her story to reporters.

“Mrs. Greenbaum drove me home about 7:30 Tuesday evening,” Pearl said. “She always drove me home. They seemed just as happy as anything. Mr. Greenbaum said his back was bothering him some. It bothered him every once in a while.”

Pearl returned to work at the Greenbaums’ shortly before noon the next day, December 3, using her key to get in. While in the kitchen, she noticed that, oddly, some frozen food she removed the night before remained on the counter. “That’s when I opened the door of the den and saw [Bess] on the couch,” Pearl said. “And, God, I just ran out of there and went to a neighbor’s.”

Bess’s lifeless body lay face down on a divan. She was fully dressed, shoes and all, her wrists bound behind her by a necktie (at first thought to have been one of Gus’s ties, but police considered it a cheap one with the label removed and not likely to Greenbaum’s tastes). A severe blow from a blunt object – police surmised a heavy decorative glass bottle found beside Bess’s head – fractured her skull. Pillows were on the sides of her head, perhaps to stifle her cries. A wound from her neck bled onto a section of a newspaper, a towel and pillow carefully placed under her by the killer to keep blood from dipping onto the carpet. The attacker used a razor-sharp nine-inch butcher knife, from a matched set in a drawer in the Greenbaum’s kitchen, to slit her throat, probably after hitting her on the head. The knife sat inside a cellophane bag over her feet. The killer employed the bag as a glove to avoid leaving fingerprints on the knife.

Pearl did not know what had happened to Gus the night before. When police arrived December 3, inside the bedroom 50 feet from Bess, they found his body laying across the couple’s twin beds, pushed together. The television, Greenbaum’s heating pad and a table lamp were on. As with Bess, two pillows lay on either side of his head as if to muffle his screams.

Two hard blows to the rear of his skull each produced fractures. Someone slashed his throat with the same knife used on Bess, nearly decapitating him. He was dressed in beige silk pajamas. Police later found out that $2,000 in cash was missing, as was a three-carat diamond ring, valued at $3,000, removed from Gus’s hand. His pricey wristwatch remained on a nightstand. Bess’s purse contained $110 in cash. Furs and other jewelry valued at about $5,700 were not taken.

Photos of Bess Greenbaum’s bound body were widely publicized in newspapers. The New York Daily News ran it on its front page on December 4.

Speculation by police about the motive for the slayings immediately centered on Mob vengeance. Investigators found no evidence of forced entry. Cigarette ashes and footprints by the garage led police to believe that two men lay in wait for Bess to leave with Pearl. The two women may have left the side door unlocked. The killers then entered without breaking in and murdered Gus. When Bess quickly returned, they hit her over the head, bound her hands, then perhaps when she came to, slashed her throat to eliminate her as a witness.

A few days later, Phoenix Police Captain Orme Morehead announced that officers had recovered some fingerprints from the crime scene. “We are checking them out. We don’t have any other leads. We have much talking and much footwork to do.” In May 1959, Morehead returned to Phoenix from a trip to confer with police in Las Vegas, but said that there were “no likely suspects.”

Ben Goffstein, Greenbaum’s partner at the Riviera Hotel in Las Vegas, offered a $10,000 reward for any tip leading to an arrest and conviction. There were no takers.

Phoenix Police suspected Milner Jarvis, a 60-year-old man seen in Las Vegas two weeks before the murders, several years after his release on parole from the Nevada State Prison. In 1948, a judge had sentenced Jarvis to 1 to 14 years for stealing $45,000 of Greenbaum’s money from a strong box while a clerk at the Flamingo Hotel. Greenbaum himself swore out the complaint alleging that Jarvis and a second man (also later sent to state prison) took the cash. But there was no evidence to pin the murders on Jarvis or the other thief.

In Nevada, state authorities expressed doubt that organized crime was behind the Greenbaum slayings. On December 19, William Deutsch, a member of the state Tax Commission regulating Nevada casinos, remarked that he had “received indication” linking the killings to gambling business matters. But Robbins Cahill, chairman of the Gaming Control Board, Nevada’s investigative arm for gaming licenses, replied that “the crime doesn’t look like a syndicate job.”

“It was too messy,” Cahill said. “It was more like a crime of passion. The killer didn’t even use his own weapon – he used a butcher knife from the Greenbaum kitchen.”

Cahill persuaded Deutsch that Nevada’s gaming agency did not include experts in homicides and that any involvement by the state would only frustrate the investigation by Phoenix Police.

Five weeks after the homicides, with no suspects yet, the U.S. Justice Department convened a federal grand jury in Los Angeles to investigate the Greenbaum slayings and organized crime activities in California and Arizona. One of the witnesses under subpoena was Tucson, Arizona-based Mob boss Joseph Bonanno. At the same time, Attorney General William Rogers announced other grand juries in New York, Chicago and Miami as part of an inquiry into the nation’s “100 top hoodlums,” including those who attended the November 14, 1957, summit of major Mob leaders in Apalachin, New York.

Greenbaum, until a police crackdown on illegal gambling in 1948, served as overseer of Phoenix’s bookmaking racket and race wire for many years. Born in Chicago, Greenbaum joined Al Capone’s Outfit in the 1920s. Capone sent the young Greenbaum to run the Mob’s rackets in Phoenix in 1928.

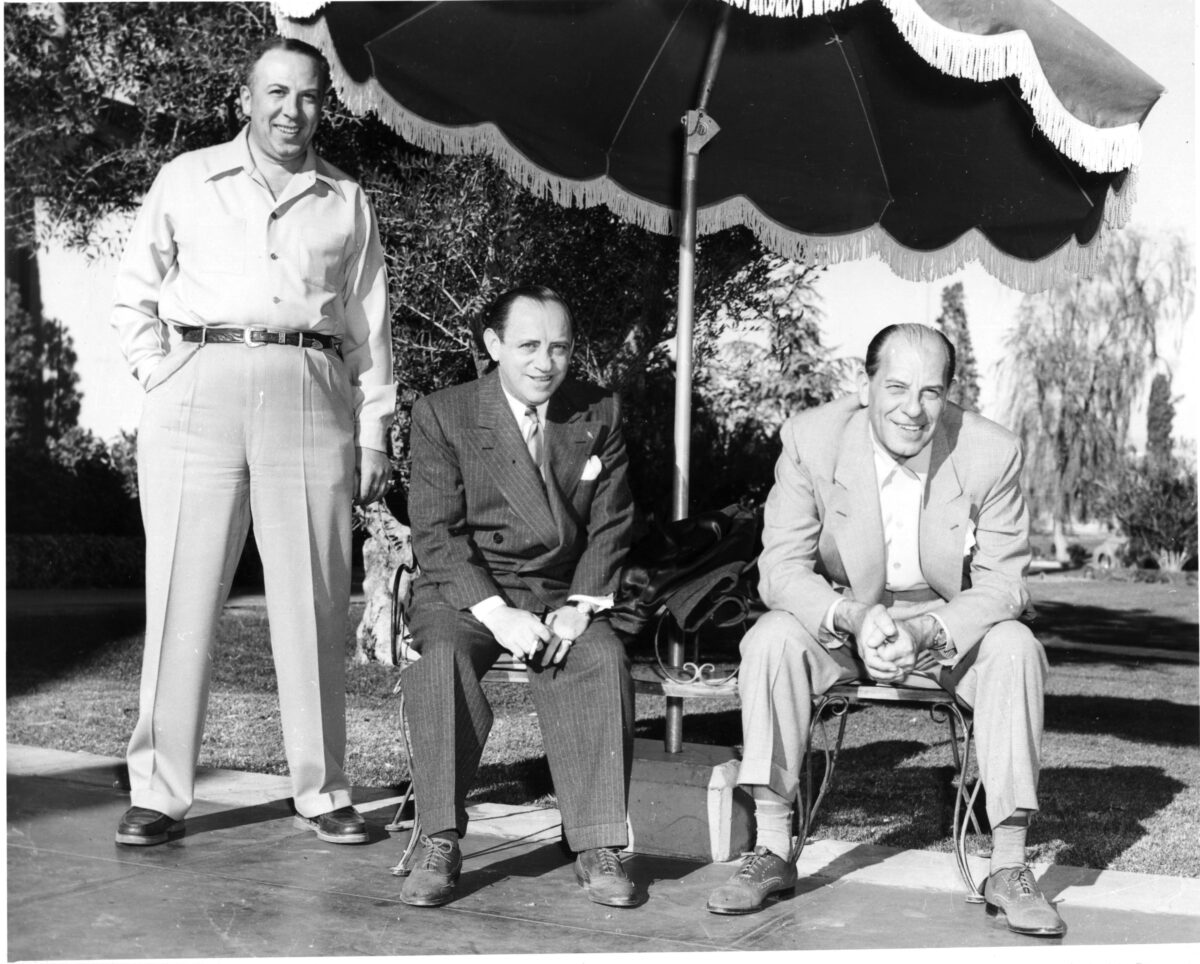

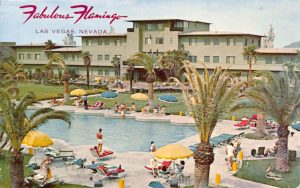

In the early 1940s, Greenbaum started obtaining interests in Las Vegas and developed close ties to West Coast race wire racketeer Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel. He invested in the El Cortez hotel-casino in downtown Las Vegas. Greenbaum’s expertise in illicit and legal gambling would prove instrumental. Siegel racked up large debts at the mob-backed Flamingo Hotel, and died of gunshot wounds, most likely at the behest of his Mob partners (including Meyer Lansky and Frank Costello), in 1947. The same mobsters assigned Greenbaum, along with Morris Rosen and other Mob associates, to take the reins. Under Greenbaum’s leadership, the Flamingo soon garnered high profits.

When the Flamingo sold for $9 million in 1954, news stories claimed that Greenbaum and his grateful Mob stakeholders profited by about $4 million. However, Greenbaum reportedly owed Chicago Outfit boss Tony Accardo $1 million, a loan to refurbish the Flamingo.

Still managing the Flamingo following the sale, Greenbaum commuted by air from Las Vegas to his house in Phoenix. A popular figure in Las Vegas, he was dubbed the “mayor” of Paradise, the unincorporated township in Clark County (south of the Las Vegas city limits) that included the Las Vegas Strip.

Greenbaum had lived with threats from his greedy casino colleagues for years leading up to his death. In early 1955, with the Flamingo sold, and the overbuilding of casinos about to do harm to the Las Vegas casino economy, Greenbaum debated retiring from casino management, selling out, moving to Phoenix for good, maybe play golf with his buddy, Arizona U.S. Senator Barry Goldwater.

The Riviera opened on April 20, 1955. Its Miami-based partners, including Mob chief executive Lansky who owned a hidden interest, could not make a go of the $10 million, nine-story Riviera. The overhead was huge. They agreed to pay pop star pianist Liberace a then-record $50,000 a week. Right away, the hotel owed $1.4 million in construction bills, $800,000 to trade creditors, and a bankruptcy filing loomed. Greenbaum’s ruthless Chicago Mob commander, Accardo, demanded he take his prized Flamingo team over to run the Riviera. Gus refused.

Then on April 27, 1955, Gus’s brother Charley returned from the racetrack to find his wife, Gus’s sister-in-law, Leone McLead Greenbaum, on the floor, smothered – by “human hand” over her nose and mouth, the medical examiner later concluded – in their house in Phoenix. Charley reported nothing missing from the home. Police never caught Leone’s killer.

Gus realized what was at stake – his and his family’s lives – and agreed to assemble his Flamingo management team, a motley crew of casino toughs that included veteran Mob associates Israel “Ice Pick Willie” Alderman and Davie Berman, to take over the Riviera.

Nevada’s Tax Commission, then the final word in licensing investors in the state’s casinos, “threw a life preserver” to the Riviera, as the Reno Evening Gazette put it in September 1955. The panel reluctantly accepted Greenbaum’s proposal to be the casino’s managing director, have its new investors lease the Riviera for $104,000 a month and pump in $1.5 million to cover debts and a $250,000 casino bankroll. Commissioners, however, approved only eight of the 14 applicants because of uncompleted background checks. Those given licenses included Alderman, Berman and Mob-connected former nightclub owner Ross Miller.

Tax Commissioner William Sinnott, an ex-FBI agent, said he voted for the plan only to maintain the financial welfare of Las Vegas. He warned Greenbaum and his partners about the “great obligation” they incurred to the state for permitting them to operate despite some having police records “dating pretty far back in the twenties and thirties.”

“I won’t vote on the same basis again,” Sinnott said.

By 1958, Greenbaum and his team had succeeded in turning around the Riviera as it had with the Flamingo. Gus owned about 22,000 shares, worth $370,000 (about $3.2 million in 2018) in the Riviera, and served as hotel president. He also retained a $92,000 investment (nearly $800,000 in 2018) in the Flamingo and a smaller stake in the Las Vegas Club.

But Greenbaum had developed serious personal problems. He reportedly used heroin regularly to treat his aching back, drank heavily, frequently lavished money on prostitutes, gambled away thousands at a time and allegedly skimmed casino proceeds to pay for it.

This loss of cash for the Riviera’s concealed mobster interests angered Accardo and his sidekick, former Capone payoff man Jake “Greasy Thumb” Guzik. Accardo reportedly demanded Greenbaum sell his shares and leave the Riviera. Chicago Mob fixer Johnny Rosselli later claimed that Accardo sent him to Las Vegas to persuade Greenbaum to unload his investment. If he did that, Accardo would consider them even, and he could walk away, despite the skimming. Rosselli said that Gus replied: “I don’t want to leave. This goddamn town is in my blood. I can’t leave.”

Since there were no arrests or charges filed in the Greenbaum murders, the motive, and what actually happened, is open to conjecture. Phoenix Police theorized the murderers came from Miami, as two unidentified suspicious men arrived in Phoenix the day of the killings and left immediately for Miami.

Rosselli would say that Los Angeles mobster Jimmy “The Weasel” Fratianno informed him years later that Lansky, a Miami-based silent partner in the Riviera who was losing money because of Greenbaum’s erratic behavior, wanted Greenbaum eliminated. For mobsters such as Lansky, Greenbaum was bad for business and deserved permanent removal, as did Siegel for mismanaging the Flamingo in 1947.

“That was Meyer’s contract,” Fratianno said, according to Rosselli.

Chicago Outfit enforcer Marshal Caifano, working for Accardo, also supposedly approached Greenbaum in Las Vegas in 1958 and told him, “Sell out or you’re gonna be carried out in a box.”

Weeks before the slayings, Greenbaum, while in Las Vegas, hired two bodyguards and was seen walking with the guards on his way to vote in the national election on November 4. He had not used bodyguards before. The Arizona Republic reported that a person or persons intended to “raid” the Riviera’s count room but “the plot was thwarted after a tipoff to authorities.”

Greenbaum employed the bodyguards “after a reported dispute” at the Riviera, the paper reported. “Employees of the Riviera and other Las Vegas casinos have been fired recently from high-paying jobs and apparently have blamed Greenbaum for it.”

He left Las Vegas the week before his murder. He flew to Phoenix and had family members and Pearl over for Thanksgiving dinner on November 27. One story goes that while Greenbaum and his family enjoyed their Thanksgiving meal, an unusual holiday meeting took place more than 100 miles away at a large ranch in Tucson owned by Detroit Mob boss Pete “Horse Face” Licavoli, who at the time was in federal prison for tax evasion. Without their host, Chicago boss Accardo, New York crime family bosses Joe Profaci and (Tucson resident) Joe Bonnano, and Accardo’s brother-in-law Joe Magliocco, conferred at Licavoli’s. The gathering was nicknamed the “Four Joes” meeting. Did they convene, at least in part, to seal the fate of Greenbaum, slain with Bess five days later?

Greenbaum’s death did nothing to help the mobbed-up Riviera. By summer 1960, former Cleveland mobster Moe Dalitz and his Desert Inn group filed for emergency permission with the newly formed Nevada Gaming Commission to infuse the Riviera with $760,000 and send the D.I. management team over to operate it. The commission balked, saying the Dalitz clan already controlled the D.I., Stardust and Royal Nevada on the Las Vegas Strip.

The D.I. group made a quick phone call to the president of First National Bank of Nevada, who said the Riviera would have to close within a week without new cash. The banker agreed to grant a loan of $250,000 to the Desert Inn guys and a two-month extension on a separate $100,000 loan. The commission tabled the request.

But the D.I. men pulled a fast one. Despite pleading poverty, the Riviera somehow came up with lots of cash. It put up $180,000 to buy out four investors employed as casino supervisors (including Sid Wyman and George Duckworth, indicted with Lansky in 1971 for allegedly skimming at the Dunes Hotel).

Then Riviera President Ben Goffstein hired some Desert Inn and Stardust casino and entertainment supervisors away to work at the Riviera. The Gaming Commission could do little about it. Nevada’s gaming control law, passed by the Legislature in 1959, did not explicitly provide rules on licensing key hotel employees.

“It appears that once we trust a license to a man, he can turn around and laugh at us,” lamented Gaming Commissioner Bert Goldwater in Carson City on October 18, 1960. “Do we have the power to control this type of activity? If not, I think the statutes are ineffective and the purpose of the law defeated.”

Two days later, the Riviera’s Goffstein, in an interview with the Reno Evening Gazette, defended his management moves, saying the state government could not “stop us from hiring the personnel we feel we need. This seems contrary to all principles of free enterprise which we enjoy.”

This time around, the Mob pulled off a bloodless coup, although several weeks later the Desert Inn did agree to withdraw its employees from the Riviera.

The Greenbaum-Riviera saga essentially ended in 1961 when the Gaming Commission allowed his daughter, Sara Jean Tenebom, to sell Greenbaum’s remaining 12.5 percent stake in the Riviera to the hotel’s corporation, worth $250,000.

The Chicago Outfit continued to skim casino cash from the Riviera. In 1967, a federal grand jury in Las Vegas indicted seven casino executives, including three partners in the Riviera (Ross Miller, Frank Atol and Joe Rosenberg), on tax evasion charges based on skimmed gaming proceeds. The IRS determined the Rivera siphoned at least $23,000 from $133,000 in casino income reported from April to June 1963 alone. But a Las Vegas judge agreed to drop the case in April 1968 with only two executives, Rosenberg and former Fremont casino president Ed Levinson, paying minor fines for pleading no contest to filing false tax returns for the casinos.

Less than a month later, in May 1968, three investors headed by Beverly Hills entertainment lawyer Harvey Silbert bought out the Riviera’s shareholders to acquire the hotel. Ross Miller resigned from the board.

The Riviera disappeared after its implosion in 2016. Las Vegas convention officials bought the property to build extra meeting space.

Gus and Bess Greenbaum lie buried within a few feet of each other, inside twin bronze caskets at Phoenix’s Beth Israel Cemetery. Several feet to the right is the grave of Leone Greenbaum.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org