White Boy Rick: From Teenage FBI Informant to Poster Boy for Criminal Justice Reform

In 1980s Detroit, the FBI employed 14-year-old Rick Wershe as an informant to bring down a drug kingpin. He was rewarded with more than 30 years in prison

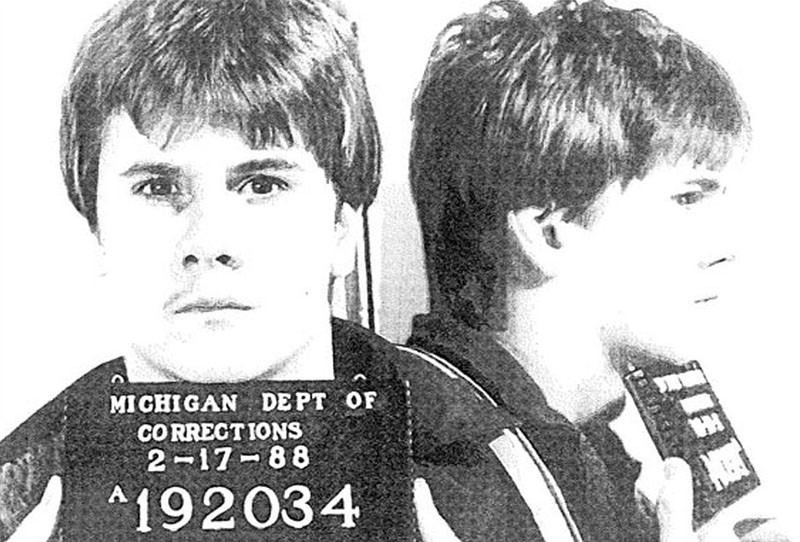

Richard “White Boy Rick” Wershe is a living, breathing casualty of America’s war on drugs, locked away for the past 31 years on a cocaine-possession case derived from a routine traffic stop when he was 17. He’s the nation’s longest-serving nonviolent juvenile offender, incarcerated since January 1988 based on a law (known as the “650 Lifer Law”) that was ruled unconstitutional more than two decades ago.

But this case goes a lot deeper than a 17-year-old running a stop sign and getting busted with blow. It’s a complex web of deception, political power plays and police corruption that started well before he was arrested on a sunny spring evening in 1987 in his grandmother’s front yard. This July, Wershe will turn 50. He will celebrate this birthday the same way he has every one of them since he was 18: behind bars. His earliest possible release date is in late 2020.

Hollywood adapted his life story into a film last fall starring Oscar-winner Matthew McConaughey and newcomer Richie Merritt in the title role. What flashed across the screen for those two hours in theaters around the world only scratched the surface of this hard-to-believe tale of the drug war run amok.

What you eventually learn when digging deeper into the story of White Boy Rick is that he is essentially serving time for the sins of others. He is a relic from a bygone era, preserved in a prison instead of a museum, collecting dust for going on three decades.

Wershe grew up on the gritty east side of Detroit in the 1970s and early 1980s. It was a time when the city was in a freefall, a once-mighty metropolis devastated by the lingering effects of the 1967 race riots, a financial and identity crisis tied to the restructuring of the auto economy – on the shoulders of which the city itself was built and thrived for so many years – and alleged rampant graft running through City Hall and police headquarters. Within this context, Wershe was a baby-faced, precocious Little League baseball star with no idea what fate had in store for him the week he left eighth grade. He’d soon be living a movie.

The Wershe family (Rick, his father, sister and grandparents) were one of the last white families living in the city at the time the FBI came calling on Rick’s dad, Richard Sr., in June 1984 for information on a drug kingpin named Johnny Curry. Richard Sr. was a street hustler and arms dealer who had given information to law enforcement in the past in exchange for money. But he knew nothing about the area’s drug scene. His son, 14 years old and just days removed from graduating junior high, didn’t know the dope game either, but he knew the neighborhood. And he was savvy for his age, fast-talking, quick-thinking, highly intelligent, naturally charming and, most of all, completely unsuspecting.

By the end of the month, the FBI had brought Rick onto the payroll to work with a narcotics task force as a confidential informant. He was encouraged to drop out of high school and sent undercover into Johnny Curry’s organization for the next two years, pocketing almost $50,000 for his risky intelligence-gathering endeavors. In a matter of weeks, he proved to be a prodigy on both sides of the law.

Wershe became Curry’s protégé, and Curry gave him a nickname: “White Boy Rick.” His mink coat-draped, diamond-encrusted Rolex-wearing (government-sponsored) rise in an underworld dominated by men twice his age and all of a different skin color transfixed the media and surprised even the agents and detectives he was working for. Soon, hit television shows such as Miami Vice and 21 Jump Street were crafting storylines centered on swaggering teenage dope boys inspired by the headlines coming out of Motown.

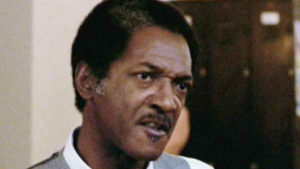

The task force was targeting Curry because they saw him as a way of leading the feds to the doorsteps of bigger heads to mount on their wall, such as the controversial mayor of Detroit, Coleman Young, and Detroit Police Department homicide commander Gil Hill. Curry was married to Young’s favorite niece Cathy Volsan, and he was in frequent communication with Hill, who gained fame for portraying Eddie Murphy’s boss in the Beverly Hills Cop movie franchise.

With the information provided by Wershe as the cornerstone of the investigation, the feds indicted Curry and several of his lieutenants in April 1987. They all pleaded guilty to drug and racketeering charges. The Curry case never led to the mayor’s office or to wrongdoing in the police department. Upon the investigation entering its final stages in late 1986, the task force had broken off its relationship with Wershe. The indictment against Curry was already in the bag, so he was no longer needed.

For a brief period, with Curry out of the picture and unfettered by any connection to the government, the 17-year-old Wershe tried to take over Curry’s territory and become a cocaine wholesaler on his own. He also dated Cathy Volsan, six years his senior, and sat courtside at Detroit Pistons basketball games with a large entourage, factors that obviously only intensified the media scrutiny surrounding him.

Wershe didn’t make it very far as a “weight man.” He was busted for having eight kilos of cocaine that he had stashed under a neighbor’s porch in the wake of a May 22, 1987, traffic stop. He was found guilty at a January 1988 trial held in Detroit’s Wayne County Recorder’s Court and sentenced to a mandatory minimum of life in prison without parole per Michigan’s 650 Lifer Law.

Three years into doing his time, in 1991, right before his 21st birthday, Wershe reconvened his relationship with the FBI and began helping the agency build more cases. His cooperation was a key to dismantling the biggest dirty cop ring in Detroit history – a corruption scandal with links to both Mayor Young and Gil Hill (neither was ever charged) – and bringing down the murderous Best Friends drug gang that was responsible for littering the streets of Detroit with bodies in the late 1980s and early ’90s. Prosecutors and Drug Enforcement Administration bosses lauded Wershe as the most effective confidential informant of his era. They were astounded at the amount of high-quality intelligence he was able to provide them.

That cooperation made him some powerful enemies, just as much with the “good guys” as with the “bad guys.” Young and Hill made no secret of their disdain for Wershe. The mayor called him a “stool pigeon” in a television interview. According to those close to him, Hill later blamed Wershe’s finger-pointing in his direction for the cover-up of a murder and subsequent questions raised for ruining his own mayoral bid in 2002. An FBI informant and former hit man claimed Hill gave him a murder contract on Wershe in the months before Wershe went on trial.

Johnny Curry was released from prison in 1999. Coleman Young left office in 1994 after 20 years on top – hunted, but never caught. He died of emphysema in 1997. Hill became the president of the City Council before dying of natural causes in 2016.

Through all those years, Wershe could never get paroled. After the law he was sentenced under was thrown out by the Michigan State Supreme Court in 1998, every single person convicted, besides him, was freed within six years. The parole board considered Wershe for parole in 2003, 2008 and 2012 and he was rejected without explanation all three times.

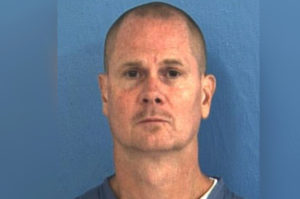

Finally, in August 2017, with a Hollywood film coming down the pike ready to shine a giant light on the whole sham of a predicament, Wershe was granted parole from Michigan. Today, Wershe is in a Florida prison, completing a sentence for a minor role he played in a stolen car ring from prison in the early 2000s. He’s scheduled to be released in October 2020.

Scott M. Burnstein, an author, journalist and organized crime historian from Detroit, has been writing about the Rick Wershe case since 2007 when he was the first reporter to confirm Wershe’s undercover work for the federal government as an adolescent. In 2017, he executive produced a critically acclaimed documentary chronicling Wershe’s struggle for freedom called White Boy, which is appearing this spring on the Starz cable channel. He worked for three years (2015-2018) as the official script and technical consultant on the Hollywood film.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org