Last call before the Dry Decade

One hundred years ago tonight, America enjoyed legal liquor for the last time before Prohibition

At 12:01 a.m. on January 17, 1920, “last call” parties wrapped up across the nation, as the United States officially began enforcing federal Prohibition. Many Americans mourned the loss of legal liquor at bars, clubs and hotels. Newspaper accounts characterized these events as relatively quiet and somber, as Americans prepared for what would become thirteen dry years.

While Prohibition proponents took their final legal sips and carried out symbolic funerals for liquor, wine and beer, many Americans cheered. Famous outfielder-turned-preacher Billy Sunday proclaimed to a revival crowd in Norfolk, Virginia: “Men will walk upright now, women will smile, and children will laugh. Hell will be forever for rent.” Temperance reformers in Louisville, Kentucky, hosted a funeral for “John Barleycorn” – a derogatory nickname for alcohol – though their funeral had a more worshipful tone than the last call parties.

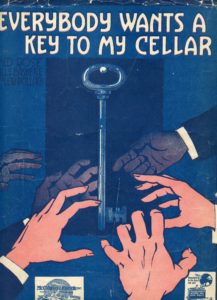

In those early-morning hours, revelers trudged home. The wealthiest “wets” may have consoled themselves with private stockpiles. In the days and months leading up to Prohibition, individual households amassed shipments of scotch and champagne, casks of bourbon and cases of wine in their private cellars.

Prohibition outlawed the manufacture, sale and transport of alcohol. It never technically made it illegal to drink. Prohibition also included a series of loopholes. Americans could still drink sacramental wine, which led to an increase in self-proclaimed rabbis and ministers. They could go to the doctor and obtain a prescription for medicinal liquor to ease their suffering. Finally, scientists and manufacturers still had access to industrial alcohol, although its suitability for drinking varied.

Besides the ambiguity of whether consumption was breaking any laws, enforcement was uneven and drastically varied depending on the community. New York officials announced they did not intend to carry out any “spectacular last-minute raids” during the first few hours of Prohibition, as reported in the January 17 edition of the New York Times. The state of Maryland never enforced Prohibition at the state or local level, on the grounds that it infringed on state’s rights. On the other hand, there were twenty-one states that had been dry since before World War I. In those states, mostly in the South and Midwest, law enforcement was raring to go.

Acknowledging that public opinion about Prohibition was mixed even in already-dry states and counties, law enforcement officials asked clergy to aid in informal enforcement. Internal Revenue Service commissioner Daniel C. Roper urged clergymen, “The public mind must be clarified, misunderstanding of the situation swept away, and the right spirit aroused” in order to accomplish “the sobriety of manhood [and] the supremacy of law and order.”

Unintended consequences

Prohibition had many unintended consequences, not least of which was the dramatic increase in criminal activities. In the early morning of January 17, two stills were shut down and confiscated in Detroit. Although some local officials chose not to enforce the law until daybreak, the cities that did begin busting people immediately reported hijackings, burglaries and still busts. As the month of January continued, enforcement began in earnest. On January 26, Chicago Mayor A.V. Dalrymple announced that local officials would begin to search and seize liquor held outside of households, which meant that noncompliant hotels and social clubs, as well as anyone trafficking liquor, could expect legal repercussions. On January 29, agents in New York — which was notorious for half-hearted enforcement throughout Prohibition — began seizing one- and five-gallon stills. On February 11, forty Prohibition agents seized twenty-five stills in Terre Haute, Indiana. The reign of the Prohibition agents had begun.

One of the hardest hit cities was Chicago. In the early morning of January 17, masked bandits emptied two freight cars of whiskey and stole four casks of grain alcohol from a government warehouse. In Chicago’s wealthiest neighborhoods, many of the private stockpiles of liquor, just recently delivered from international shipments or previously public wine cellar clubs, were burglarized. Reports of thieves stealing liquor but leaving behind jewelry, cash and silver began in the last months of 1919 and continued for years. Gangs across the city, notably Dion O’Bannion’s North Side Gang and Johnny Torrio and Al Capone’s South Side Gang, competed for control of the illegal liquor trade. Violent turf wars erupted, as millions of dollars changed hands.

These Chicago turf wars were particularly bloody, but they were not isolated. Prohibition was the best thing to ever happen to organized crime. In cities across the nation, but particularly along land and ocean borders, mobsters became millionaires. In New York, the Five Families of the Italian-American Mafia worked with Jewish mobsters to import top-shelf liquor from Europe, Canada and the Caribbean. Meyer Lansky and Charles “Lucky” Luciano began importing Scotch from Great Britain in 1920. In Chicago, Al Capone relied heavily on proximity to the Canadian border. His South Side Gang oversaw smuggling rings that ranged all the way up to Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. Detroit’s Purple Gang relied on its neighbors in Windsor, Ontario, to ensure their liquor supply remained healthy.

These operations required violence, extortion and bribery to succeed. Although public drunkenness, disorderly conduct and alcohol consumption did decrease during Prohibition, bootlegging crimes grew. So did companion activities including tax evasion and murder. In 1919, the national homicide rate was 7.2 per 100,000 people, but by 1933, it had climbed to 9.7. Even some of Prohibition’s most ardent supporters realized that what was intended to make the nation healthier, wealthier and safer had in fact done the opposite.

Prohibition also created public health challenges. Although public drunkenness and cases of cirrhosis decreased, individuals who did get sick from drink were often in far worse straits. A new health threat involved tainted alcohol sold on the black market. On January 17, 1920, in the Rice Belt Journal (Welsh, Louisiana), an article titled “Meet Ethyl and Methyl Alcohol” appeared alongside another declaring, “Prohibition Is Now Reality in America.” Public health officials hoped to warn uninformed consumers that some bootleggers would try to pass off poisonous methyl (or wood) alcohol as liquor. In 1923, 321 people died of wood-alcohol poisoning. Several thousand others died before the end of Prohibition.

In 1930, an estimated 50,000 to 60,000 people were permanently paralyzed from a popular over-the-counter tonic called Jamaica Ginger, commonly referred to as Ginger Jake. Jake was a medicinal tonic used to settle upset stomachs, and it was produced with as much as 80-90 percent alcohol. Since it was both medicinal and over the counter, it was available to the public throughout Prohibition, and it became a popular product for thirsty lawbreakers.

By 1930, the U.S. Treasury Department had passed regulations requiring manufactures of such tonics to modify their taste with bittering agents. A pair of bootleggers, Harry Gross and Max Reisman, decided to circumvent the law, and they worked with an MIT professor to develop an addictive that passed government tests without affecting the flavor. The group added tricresyl phosphate, which was commonly used as a plasticizer and flame retardant. Unfortunately, as they later discovered, it also was a neurotoxin that led to paralysis in the legs and feet.

Prohibition and women

Of course, Prohibition had positive consequences, many of which affected women. Before the 1920s, women rarely set foot in saloons, and they only visited hotel bars and restaurants with a husband or another appropriate male chaperone. But speakeasies were frequented by men and women fairly equally. In an environment where everyone was breaking the law, societal norms began to break down. Men and women began dating without supervision. Women dressed in the fashionable “flapper” style, with bobbed hair, makeup and dresses at or above the knee.

Broader changes to women’s roles in American society coincided directly with Prohibition. Women including Bessie Smith, Fannie Brice, Sophie Tucker and Josephine Baker, built professional performing careers in speakeasies and clubs. Female journalists found jobs reporting on everything from Hollywood to rum running. Louella Parsons was America’s first movie columnist. Lois Long, under the pseudonym “Lipstick,” penned witty pieces about New York society for The New Yorker. And “The World’s Greatest Girl Reporter,” Adela Roger St. Johns, wrote about crime, politics and sports.

Even politics and government work was suddenly a possibility for women. Two such women stand out for their differing roles in Prohibition: Mabel Walker Willebrandt and Pauline Sabin. Historians Hugh Ambrose and John Schuttler examined the lives of these two women in a 2018 book, Liberated Spirits: Two Women Who Battled Over Prohibition.

Willebrandt served as assistant attorney general from 1921-1929. The second woman to hold the position, at just thirty-two years old she was the highest-ranking woman in the federal government. Willebrandt did not personally support temperance, but she was a staunch defender of the Constitution, and she worked to enforce Prohibition tirelessly. Willebrandt had her work cut out for her.

The state directors of the newly formed Prohibition Bureau often lacked law enforcement training and experience. They not only often failed to catch and arrest serious Prohibition offenders, but even when they did crack a case, they often could not provide the proper evidence or produce the proper paperwork in order to prosecute. When Seattle bootlegger Roy Olmstead’s first federal trial was botched by Prohibition agents, Willebrandt became more active in building cases. She directed district attorneys to build relationships with Prohibition agents to guide evidence collection and ensure legal execution of search warrants.

Willebrandt remained convinced throughout Prohibition that the lack of local support, inefficient coordination between federal agencies and what she referred to as “entirely too much politics” were responsible for Prohibition’s failure. Before Prohibition, supporters had pushed state and local measures and lobbied schools and community organizations to tout temperance. As soon as Prohibition passed, many of these reformers either moved on or placed their full faith in the federal government.

Her criticism and determination paid off, at least in small measures. In 1924, the Treasury secretary authorized a transfer of $150,000 to the Department of Justice, earmarked to direct investigations into large-scale smuggling operations. Even with this relative windfall, Willebrandt continued to fight for the necessary resources to enforce Prohibition.

Pauline Sabin came from a wealthy, politically connected family in New York. She initially supported Prohibition on the basis that it would create a better world for her two sons. In 1914, after a divorce from her first husband, she established an interior design business in New York. By the 1920s, she was active in women’s political clubs and the Republican Party. She helped to found the Women’s National Republican Club (WNRC) with Henrietta Wells Livermore in 1921. That Sabin would later change her opinion on Prohibition and found the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform should come as no surprise to people familiar with her early years in politics.

Sabin was a traditional Republican who favored small government and believed in conservative and pragmatic laws. As many women rallied behind the Equal Rights Amendment in the early 1920s, she cautioned that it was too vague and that it would roll back protections that women were afforded in the workplace. She actively distanced herself from the idea that women had specific pet issues. Her husband, Charles Sabin, opposed Prohibition as did Republican Senator James Wadsworth, who Pauline supported beginning in the mid-1920s. By the mid-term elections of 1926, she still supported Prohibition, but she actively opposed increasing New York’s power of enforcement.

During the 1928 presidential election, both Willebrandt and Sabin supported Herbert Hoover. Willebrandt believed he was the only person who could faithfully restore lawfulness and ensure Prohibition’s enforcement. Sabin, on the other hand, had preferred other Republican candidates to Hoover, but she begrudgingly supported him as the party’s final nominee. Part of her lukewarm reception to Hoover was her new position on Prohibition. In June of 1928, she announced that she no longer supported the 18th Amendment.

Both women came to regret their support for Hoover once he took office. Willebrandt resigned in May 1928. Before she did, she tried to lobby to move all Prohibition enforcement into the Department of Justice, a move that Hoover blocked. Her first legal client after she left the government was California Fruit Industries, a wine and juice maker. That same month, Sabin founded the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Repeal (WONPR). She had already realized that Hoover’s preoccupation with Prohibition was exactly the opposite of what she wanted in a president.

Both Sabin and Willebrandt paved paths that few women could in the 1920s. Willebrandt adopted a daughter in 1925, though she was estranged from her husband, and she traveled with her daughter, Dorothy, whenever she could. She held out for a judgeship through countless administrations, and she did all of this while hiding worsening deafness that plagued her whole life. Sabin went from a club woman to a political actor in less than a decade, and her organization, WONPR, played a vital role in Prohibition’s repeal four years after its founding.

But on January 17, 1920, no one could have anticipated the thirteen years that would come to pass. Willebrandt and Sabin were both still relatively unknown. Al Capone was still an unknown thug in Chicago. It was a new decade, but the federal ban on liquor certainly cast a pall for many. As people stumbled home from their respective festivities, some carrying souvenir bottles that had suddenly become contraband at the stroke of midnight, the nation prepared for the first of many dry evenings.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org