Culling out the card sharks

A century ago this month, authorities busted a card-marking crew in Las Vegas’ first sting operation

Gambling was always a backdrop in the nascent years of Las Vegas, a popular if illicit activity for railroad workers, cowboys and the valley’s earliest settlers. So it is no surprise that gamblers were the target of the first sting operation ever conducted by law enforcement in Las Vegas.

Nevada state lawmakers voted in 1909 to ban gambling, effective on September 30, 1910. This measure would put the brakes on illegal gambling throughout the state, while also triggering a counter-campaign to legalize the activity.

The loosening of the laws had begun in 1913 when Nevada statutes were amended so that “nothing in this paragraph shall be construed as prohibiting social games played only for drinks and cigars or for prizes of a value not to exceed two dollars.” Nor did the new law prohibit “nickel-in-the-slot-machines for the sale of cigars and drinks and no play-back allowed.” By state law, gamblers couldn’t gamble more than a nickel at a time, frustrating casino operators who wanted gamblers to put quarters and half-dollars into the machines. “Play-back,” or the reward of tokens that could be exchanged for cash for winning pulls on the one-armed bandits, hadn’t yet been authorized by the state.

In time, card tables began to flourish, offering games with fanciful names that competed for attention with the nickel slot machines that were showing up in saloons. The diversity was enticing, so gamblers and communities alike started pushing the edge of the envelope for more games of chance. In 1915, the state Legislature blew the whistle and made gambling laws more specific:

“It shall be unlawful for any person to deal, play or carry on, open or conduct, in any capacity whatever, any game of faro, monte, roulette, lansquenet, rouge et noir, rondo, tan, fan-tan, seven-and-a-half, twenty-one, hokey-pokey, craps, klondyke, or any banking or percentage game played with cards, dice, or any … slot machine played for money.”

While the 1915 legislation declared that saloon operators who overstepped the line could be guilty of a felony, the law affirmed passages in the 1913 law that allowed “social games” that paid off in free drinks, cigars or prizes worth up to $2.

Two of the signature gambling devices in today’s Las Vegas – craps and roulette tables – would not be permitted until 1931.

Enforcement demanded

In January 1919, Nevada Attorney General L.B. Fowler issued an opinion banning the use of slot machines. Directed “to the District Attorneys of the State of Nevada,” Fowler wrote, “for several years there have been in use and operations in public places in this state” devices “commonly called “slot machines,’ so well known as to require no further description. So extensive have the use and operation of these machines and devices become, and so many inquiries have been made as to their legality, that it becomes my duty to render an opinion thereon.”

Fowler said, “From a legal standpoint it is positive that such a machine is a lottery.” The attorney general pointed out that since Nevada’s Constitution states, “No lottery shall be authorized by this state,” the state Legislature was wrong when it passed an act to legalize slot machines. Fowler concluded that “peace officers,” when they see slot machines, “must recognize the unlawfulness of their existence.”

In July 1919, Fowler said it was his opinion that cities in Nevada should pass local ordinances that followed the state law regarding the licensing of gambling on the five approved card games. Fowler pointed to the key problem area: “The temptation is great for a house where said games are operated to run them on a percentage basis. This is a clear violation for the law and a felony.”

The attorney general said municipalities should pass ordinances licensing card games, and the penalty for violation of the city rules would be “revocation of such licenses.” Attorney General Fowler concluded by stating his office will “rigorously enforce this law.”

Within weeks of Fowler’s opinion, the city of Las Vegas ordered its city attorney to begin drafting a gambling license ordinance.

In the late fall of 1919, the Nevada Supreme Court took on appeal the case of Louis Pierotti, who, at his Reno cigar stand, also had slot machines. He was arrested based on Fowler’s July opinion that slot machines were illegal.

But in October 1919, the Nevada Supreme Court upended Fowler’s opinion and ruled that nickel slots were legal. The state high court ruling said in part, “It would be idle for us to deny that chance is a material element in the operation of such machines. The player hopes to get cigars or drinks for nothing.”

The justices added, “There is no doubt that nickel in the slot machines amounts to the disposal of property by chance …” However, the court ruled, slot machines are not lotteries and therefore legal under the law passed by the legislature.

While gambling houses in Las Vegas brought back poker and slot machines late in 1919, saloons were finishing their first year of Prohibition. In November 1918, ahead of the federal law, Nevadans had voted to ban the sale of alcohol.

With the Nevada Supreme Court and attorney general blessing limited gambling, the city fathers in Las Vegas reversed their earlier gambling ban. Guidelines were incorporated in the city’s new gambling code, known as Ordinance 77, that was approved on October 1, 1919.

While drinking alcohol in Las Vegas was still outlawed, gambling was clearly coming out of the closet. Ordinance 77 said clubs could be licensed to provide “any game of poker, stud-poker, five-hundred, solo or whist, played for money” — but not Hokey-Pokey, another version of poker. Moreover, with a look to the future, the city commission ruled that the license would cover “any other gambling game or games” which may be “recognized as legally by the laws of Nevada.”

There was a reason the city wanted to boost its gambling license revenue: it was suffering from the loss of liquor license revenue. Gambling houses would now have to pay a quarterly fee to City Hall of $150 – or about $2,000 in today’s dollars.

At the end of October only three locations had signed up for the last quarter of 1919: The Las Vegas Hotel on Fremont Street, the Colorado Hotel on First Street and the Union Hotel on Main Street. But Las Vegas was slowly growing. The U.S. Census counted 2,304 people living in the city in January 1920. That year, between five and eight gambling halls were licensed for at least one quarter of the year.

The gambling houses squawked at the amount of licensing fees they had to pay.

Crooked game

Maybe it was inevitable: With the legalization of gambling on card games, crooked games became prevalent in Las Vegas clubs. Complaints of marked cards being used in licensed poker games began circulating in the early summer of 1920.

A report from county District Attorney Jerry Stebenne revealed complaints of an “Armenian” losing $250, a “Mexican from Arden” losing $300, and several others reporting unusually high losses at poker games at one club. Something was wrong. Somebody was cheating, they said.

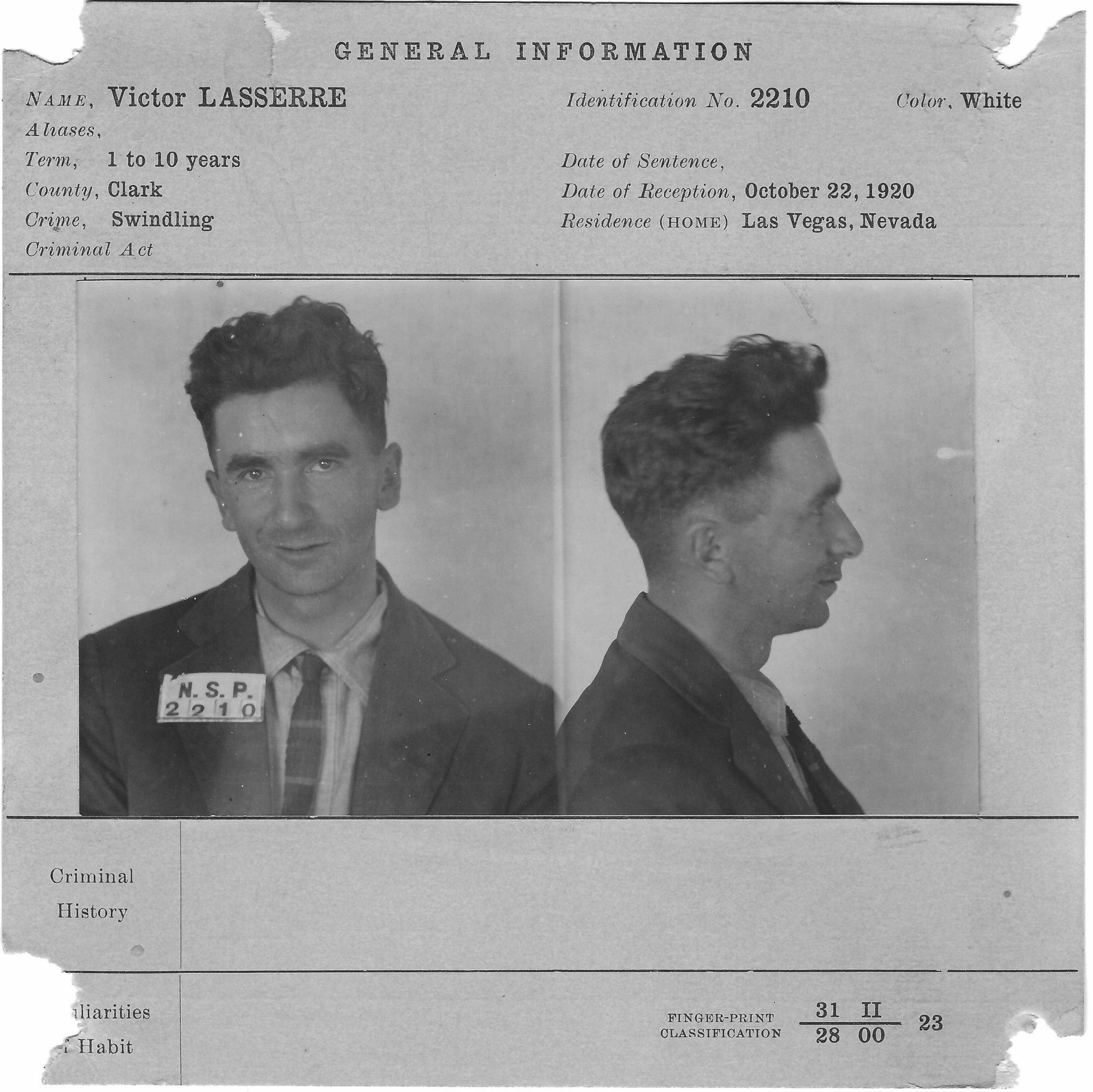

One of the losers was “Charlie” Kantanjian. Kantanjian, known to his friends as “a persistent patron” of poker, even when losing, told the district attorney that the game at a pool hall was crooked. He told to the district attorney he was a good poker player but over a period of a couple of days, he lost $350 to Victor Lasserre, aka “Frenchy.” Charlie said he wasn’t the only loser, that Lasserre was also “pulling in chips” from the other poker players as well.

After his last loss, Kantanjian told the DA he was able to get his hands on the deck of cards used in the poker game. He said it didn’t take him long to determine the cards were marked. According to Kantanjian, every card seven and above, as well as the ace, were marked. The code, on the back of the cards, visible to those who knew what to look for, revealed the suit and value of each card.

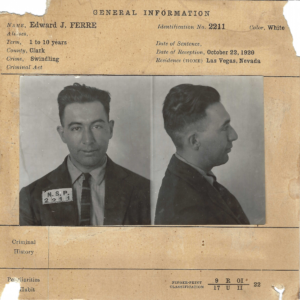

Kantanjian said he approached “Frenchy” and his partner Edward “Eddy” Ferre and told them he had figured out their scam. He demanded his money back. They admitted the cards were marked, but rather than return his money, they offered him what they said was a better deal. Ferre and Lasserre suggested Kantanjian sit in on the next few games and they would make sure he would leave a big winner, covering all his losses and more.

At this point, Kantanjian said, the owner of the gambling club, Gabriel Lopez, joined in the conversation. He told the three men he would think about their offer.

Like Lopez, Lasserre knew his way around Las Vegas.

Lasserre, a resident of Las Vegas since before World War I, told the local draft board when he registered for service in 1917 that he was born in Paris, and that his father had become a naturalized citizen.

At the time of his registration, he told the Clark County Draft Board, he was unemployed and his occupation was that of a “Saloon man.” The 26-year-old said his wife and young child were living in California.

Ninety days after he registered, Lasserre left Las Vegas on September 19, 1917, with other Clark County draftees. Within ninety days, Lasserre would be shipped to the country of his birth and served in the Army’s transportation unit. He stayed in France until he was shipped home after the war’s end.

Ferre, who was 24, single and an unemployed clerk in Kingman, Arizona, was also drafted in the fall of 1917 and sent to France.

Both were honorably discharged from the Army after two years of service.

The sting

The two men connected in the service would find their way to Las Vegas early in 1920 and become friends with Lopez. At the time, the 46-year-old Lopez owned and operated a pool hall, the First Street Club. He had properly paid the city the gambling license fee, and was operating four pool tables and two card tables. His club was located on the east side of the 100 block of North First Street, next to the city’s only bank and across the street from the offices of one of the city’s two weekly newspapers, the Clark County Review. The newspaper described its neighbor as “a noisy gambling dive.”(1)

Kantanjian’s next move: a secret meeting with District Attorney Stebenne at the DA’s private practice offices at the Nevada Hotel (now the Golden Gate Hotel). By the end of the meeting, the DA had come up with a plan that would become the first undercover sting operation in Las Vegas.

Stebenne instructed Kantanjian to tell “Frenchy” and his partner Ferre that he would take them up on their offer to let him join in a marked deck game. Meanwhile, the DA rounded up other players, including two well-known local gamblers, C.E. Whitney and Victor Matteucci. Matteucci and his family were pioneer Las Vegans, arriving in 1904.

Las Vegas law enforcement’s first sting operation took place on a Sunday night, July 11, 1920.

Sitting at the table with “Frenchy” and “Eddie” were Kantanjian and the DA’s three plants — Matteucci, Whitney and Stebenne’s friend, F.B. McGrady. Watching from a distance were Stebenne and a “special officer he hired, Joe Keate. Like Stebenne, who was running for re-election as DA, Keate was running for public office – to become the sheriff. One could say that Stebenne had stacked the deck as the players took their seats at the conniving table.

A few hands were played that Sunday night before the DA made his move.

Matteucci had a good hand, but “Frenchy” knew he had a better one. Matteucci lost the game. The DA and Keate, the candidate for sheriff, swung into action, placing the two in-house cheaters, Lasserre and Ferre, under arrest.

Lopez was not sitting in on the game but was arrested as the owner of the club.

After booking the three men in the county jail, Stebenne and Keate searched the hotel rooms of Frenchy Lasserre and Eddie Ferre. The Las Vegas Age reported that the district attorney “found in Ferre’s room five new decks of cards all nicely marked for skinning the suckers.”(2)

When Justice Court opened the next day, Matteucci filed a complaint against the trio. They were charged with “feloniously cheating and defrauding, with the aid of marked cards.” The three men hired the town’s leading defense attorney, Artemus Ham.

During arraignment on Monday, July 19, the three men pleaded not guilty. Then, on advice of their attorney, the three skipped the preliminary hearing and prepared for trial in October. Club owner Lopez was released on his own recognizance, while Lasserre and Ferre each had to provide a bond of $1,000.

Election changes

On September 7, the county’s primary election was elected. Only two candidates were running for district attorney, Stebenne and Harley Harmon. Harmon became the new DA by an overwhelming margin, 442 to 76. He would take office on January 1, 1920.

For the office of sheriff, both the incumbent Sam Gay and challenger Joe Keate made it through the primary and would face each other November 7.

A week before the trial was scheduled to begin, eight locations on Fremont and First streets were up to renew their gambling license for the last quarter of 1920. Lopez’s club was among them.

Most of the legal gambling was taking place along Fremont Street at the Northern Club, the Nevada Hotel, the Las Vegas Hotel. Lopez’s club and the Turf Saloon were on north First Street.

William Ferron, the mayor, and the three city commissioners approved all but Lopez’s license. Las Vegas City Commissioner Howard Conklin asked that it be voted on separately.

After approving the other seven licenses, the commission voted 3 to 1 in favor of granting Lopez a license. Only Commissioner Conklin voted no. The official minutes do not reflect any discussion regarding the Lopez license, or reveal why Conklin was opposed to Lopez.

Lopez went back to his First Street Club with a license for the rest of 1920.

The trial

As the trial date drew closer, Attorney Ham told the court that his clients wanted separate trials. This was granted. The fall term of the Clark County District Court began on Wednesday morning, October 13. Victor “Frenchy” Lasserre’s criminal trial was at the top of the docket.

By the end of the day, the jury was selected and testimony began. Prosecution witnesses appeared all day Thursday, Friday and into the morning of Saturday. The testimony and arguments of the DA and defense attorney Ham lasted, according to a reporter in attendance, “four weary days.”

Midday Saturday, it was time for the defense to present its case. Attorney Ham spoke to his clients, Lasserre and Ferre, saying there was not much of a defense in the face of the prosecution’s case. His advice: Plead guilty and they would likely get a lesser sentence.

As for Lopez, his prosecution was dropped for lack of evidence.

When the court reconvened on Saturday night, October 16, Lasserre and Ferre admitted to “cheating and defrauding in a gambling game by means of marked cards” and entered pleas of guilty. Each was sentenced to the Nevada state prison for one to ten years.

Within a week the two men were booked, photographed and fingerprinted at the Nevada State Prison in Carson City. Lasserre told prison officials he was a miner; Ferre said he was a merchant.

With “two of the crooked gentry” now behind bars at the state prison, the Las Vegas Age optimistically printed this understatement: “The use of marked cards in gambling games in Vegas is somewhat discouraged.”

Aftermath

While the prosecution won the day, Keate failed in his bid to take his old boss’s job as sheriff. Keate waited until Sheriff Gay retired before running for the office a decade later. This time he won.

Before long, Stebenne pulled up stakes and moved to California.

As for Lasserre and Ferre, they served nine months on their sentence and were paroled on August 22, 1921.

Lopez remained involved with the Las Vegas gambling community for the next two decades, including managing two other “colorful” operations, the Northern Club and the Miners Club. He died in Las Vegas in 1946 at age 80.

Today, given the work done by Nevada’s Gaming Control Board agents, the casinos with their experienced staff and eye-in-the-sky cameras, as well as professional card players who know what to look for, the marking of cards has been all but eliminated in major casinos.

But cheats continue trying to rip off the house, including players using everything from grease marks to infrared lights to gain an unfair advantage at a card table. The illegal marking of cards continues today as it did 100 years ago in a pool hall on North First Street in Las Vegas.

Robert Stoldal, a Las Vegas historian and longtime television news executive, serves on the Board of Directors of The Mob Museum.

Endnotes

(1) “District Attorney Springs Trap,” July 17, 1920, Clark County Review, Page 1.

(2) “Stebenne Lands Marked Card Gamblers,” July 17, 1920, Las Vegas Age, Page 1.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org