The Kefauver hearing in Las Vegas

Seventy years ago this month, the Senate committee met in Las Vegas to investigate organized crime

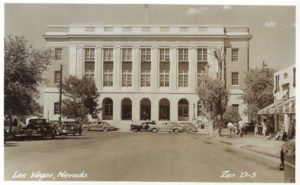

The U.S. Senate’s Special Committee to Investigate Organized Crime in Interstate Commerce, chaired by Tennessee Democrat Estes Kefauver, focused attention as never before on gambling-related crime as a national problem. Popularly known as the Kefauver Committee after its telegenic chairman, the committee captivated the nation in 1950-1951 with its televised hearings. It retains its relevance today, particularly in Las Vegas, where The Mob Museum occupies the building in which the committee met during its sole trip to Las Vegas.

The committee members held, as an article of faith proven through witness testimony (and artfully interpreted silences), that there existed a national syndicate of criminal organizations, and that this syndicate was forcing its way into legitimate businesses. It wasn’t surprising, then, that on November 9 the committee announced it would visit Las Vegas as part of a West Coast tour to learn about legalized gambling and its impact on neighboring states.

On November 14, the senators making the Western jaunt — Kefauver, Charles Tobey of New Hampshire and Alexander Wiley of Wisconsin — joined their investigators in Los Angeles. The senators and a small staff, including chief counsel Rudolph Halley, flew to Las Vegas the following morning, arriving at 9:30. The official record reflects that they convened the committee in the courtroom on the second floor of the federal building at 300 Stewart Avenue as scheduled at 10 a.m. The unofficial record is a bit messier. According to the Las Vegas Review-Journal’s A.E. Cahlan, Kefauver kept the rest of the committee — and witnesses — waiting until 11, then held a press conference before starting the hearings a half-hour later.

William J. Moore

William J. Moore was up first. An architect by trade, he came to Las Vegas in 1941 to design the Hotel Last Frontier for his uncle, R.E. Griffith, and operated the casino, which opened as the second major property on the Strip in 1942, after his uncle’s death. In addition to his duties at the Last Frontier, Moore served as a member of the Nevada Tax Commission, the administrative body that oversaw the collection of taxes from Nevada businesses, including casinos.

Chief counsel Halley probed Moore’s knowledge of the race wire situation. Next, Senator Tobey grilled Moore on the moral characteristics of his fellow gambling entrepreneurs. Moore admitted there were “a few more shady characters” than in other lines of business, and that, while it would be a “desirable” thing to purge some individuals from the industry, he had never given any thought to how it could be done, despite his license-issuing role on the Tax Commission.

Moore revealed that since the Tax Commission had begun issuing licenses, it had refused “hundreds” of applications and revoked as many as 100 for reasons of “character.” Halley asked why William Graham and James McKay, notorious Reno racketeers, had been granted licenses despite their convictions for altering government bonds in the southern district of New York. They remained qualified, Moore insisted, because of a “granddaddy clause” that allowed those who were operating before the more stringent regulatory regime was adopted to continue to do so. Mert Wertheimer of Detroit was licensed after a testimonial from “the former head of the FBI from Detroit.” Moore knew of Wertheimer’s gambling activities in other states, but insisted that shouldn’t disqualify him. “The man gambles,” he explained. “That is no sign he shouldn’t have a license in a state where it is legal.” This was “a basic policy” of the Tax Commission. After Moore explained that the Commission had just denied a license to Joseph “Doc” Stacher because of his “associates in New Jersey,” Kefauver thanked and excused Moore.

Clifford Jones

Clifford Jones took the stand next. Jones was the lieutenant governor of Nevada, a partner in the law firm of Jones, Wiener, Jones, and Zenoff, and a part owner of the Thunderbird Hotel, Golden Nugget and Pioneer Club. Halley queried him about how much he paid for each interest and the ownership structure of the Thunderbird. Halley questioned Jones on his partner Louis Wiener’s role as attorney for Dr. Maurice Siegel, executor of his brother Ben Siegel’s estate. Jones denied any detailed knowledge, deferring to Wiener, though he volunteered that Morris Rosen had “assumed a position of authority of some” of Siegel’s interests. He was aware, though, that Siegel had had an interest in the Golden Nugget’s race book. Halley then asked if Jones could ask Weiner to testify, to which Jones agreed. The committee briefly recessed.

When the committee returned, Halley asked one final question: Was it good policy to let people “whose previous records had been bad” to continue in the gambling business simply because they’d started before 1949? Jones replied that as long as the individuals conducted themselves properly, “probably no harm comes of it.” But what constituted proper conduct, Halley wanted to know. As Jones tried to answer, Kefauver interrupted him mid-sentence.

“I think we had better put the press off no longer,” the senator said. “We have put the press off here for a long while, and Mr. Jones is going to bring his partner back.” With that the committee adjourned, Kefauver held a press conference and went to lunch before returning.

When the committee reconvened, Henry Phillips, proprietor of the Last Frontier “commission room,” was sworn in. Phillips, likely sensitive to the difficulties that accepting bets across state lines might bring him, said he hadn’t been doing much of anything since taking over the commission room. “I did try to go into business,” he remarked, “but there is nobody to do business with.” He refused to admit that he accepted lay-off bets from out-of-state bookies. Moore broke in to blame the committee itself for killing the interstate race betting business.

“To be perfectly frank,” he said, “you are all running around the country investigating the race horse book and the wire and closed down all those offices.”

Phillips was excused and Jones returned with details about the Thunderbird’s race wire service.

Halley asked Jones if he knew Meyer Lansky. Jones claimed to have never met him, nor had Lansky spent time at the Thunderbird. “As far as I know,” Jones contended, “he has never been in the city of Las Vegas.” When confronted by Halley with rumors that Lansky was “reputed to live at the Thunderbird Hotel a great deal of the time,” Jones admitted that a man named Jack Lansky had been a guest at the hotel. When pressed, Jones “assumed” that this was Meyer’s brother, and that Jack had stayed at the hotel “a couple of weeks” on at least two occasions. Halley aggressively quizzed Jones on the Thunderbird’s early financial problems. Jones was certain that neither Jack nor Meyer Lansky had ever directly or indirectly loaned any money to the Thunderbird. He admitted to knowing George Sadlo, an El Paso gambler who frequently visited the Thunderbird and was an intimate of Jack Lansky’s but insisted that both men just liked to gamble at the casino. Similarly, he denied that Frank Costello had any interest in the Thunderbird, again claiming that to his knowledge Costello had never set foot in Las Vegas. Nor had he ever heard the name of Costello associate Phil Kastel.

“Is he a local fellow?” he asked Halley.

“That is all,” Halley responded, dismissing Jones and turning to Wiener.

Wiener confirmed that he was attorney for the Siegel estate’s executor, and that Siegel’s interest in the Golden Nugget race book had a value of zero. His interest in the Flamingo and a small share of the Frontier Club turf book were his only Nevada assets. Wiener admitted that Lansky might have owned some stock in the original Nevada Projects Corporation, but that “it wasn’t a large percentage.” Siegel was the largest shareholder. About two weeks after Siegel’s June 20, 1947, death, Sanford Adler and his associates formed Flamingo Hotel Inc., and bought the property from Nevada Projects. Lansky was “washed out” in this transaction. After a dispute with Rosen, Adler sold his 49 percent share of Flamingo Hotel (in a transaction brokered by Wiener and Jones) and departed for Northern Nevada. With that explanation, Kefauver thanked and excused Jones and Wiener.

Up next was Reno Police chief Lawrence Russell Greeson, who had investigated New Jersey gambling figure Joseph “Doc” Stacher. Stacher had applied for a license to become a partner in Bill Graham and Jim McKay’s Bank Club. Greeson admitted he had passed on to investigator Robinson when they met at a police chiefs’ convention in Colorado Springs the rumor that Stacher was willing to spend $250,000 to elect a group in Reno that would permit him to buy a one-third share in the Bank Club. It was “common knowledge” in town. Greeson had no opinion on the ramifications of Reno’s wide-open gambling on surrounding states and did not know of any operators currently in Reno with outside interests. Kefauver excused Greeson and moved on to the next witness, Wilbur Clark.

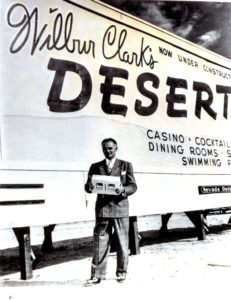

Wilbur Clark

Clark started by sharing that he was a member of the corporation that owned Wilbur Clark’s Desert Inn and an employee of the casino. He and his brother also had shares in the Barbara Worth Hotel and an unconnected cocktail lounge in San Diego. Then Clark’s powers of recollection began to falter. He was unable to recall exactly how much he had invested in the Desert Inn, possibly a quarter-million dollars? He professed not to know the hotel’s final construction cost, or the current book value of the property. Clark was not, he told the committee, in charge of the hotel’s construction or finances; that was “a boy by the name of Allard Roen.”

As Clark began explaining how the “fellows from Cleveland” had come into his project, Halley interrupted him, demanding that he “try to be a bit more businesslike in explaining these series of transactions.” Clark did his best, describing how he had approached the group — which included Sam Tucker, Moe Dalitz, Morris Kleinman and Thomas McGinty — for their help in finishing the Desert Inn. Clark first “put the proposition” to the group in Las Vegas; they rebuffed him. He approached them again in Reno three months later, and they accepted. Under terms of the agreement, the Cleveland group would fund the project to completion and provide its bankroll, receiving 74 percent of the casino’s stock. Clark retained 25 percent, and 1 percent went to newsman Herman “Hank” Greenspun. Greenspun owned a piece of property that was included in the Desert Inn’s grounds, and owned 30 percent of a motel adjacent to the hotel.

In the casino’s six and half months of operation, Clark had not yet been paid. He knew that Sam Tucker, Allard Roen and Cornelius Jones were overseeing the Cleveland group’s interest at the Desert Inn but was unsure about his own role in the operation, despite the fact that his name was on the marquee out front. Nor was Clark certain exactly who was overseeing the department heads; he thought that Kleinman and Dalitz might be in charge.

Clark said he did not know the total cost to build the Desert Inn, but was 100 percent certain he had never approached any of a list of alleged underworld kingpins whom Halley mentioned: Frank Costello, Phil Kastel, Meyer Lansky, Jack Lansky, Jack Dragna, Mike Accone and Ben Siegel. Clark testified that he was aware of but did not “have knowledge” of his partners’ various scrapes with the law, which included bootlegging convictions and illegal gambling indictments. He had heard that Dalitz was in the laundry business, but that was all.

Moe Sedway

Next up was Moe Sedway, who, unprompted, poured out a list of his physical ailments: three major coronary thrombosis, an ulcer, an upper intestinal abscess, and a six-week bout of diarrhea. “I just got out of bed and am loaded with drugs,” he told Kefauver. He shared his story: born in Poland, naturalized as a citizen in 1914, a resident of New York City until 1938, Los Angeles from 1938 to 1940, and Las Vegas from 1941 onward. He had been arrested on numerous charges, including assault and robbery, but had no felony convictions. Sedway had attended but not graduated from high school and, after a few years in the garment industry, had become a full-time gambler, dabbled in trucking, and owned a Chinese restaurant in New York.

Unlike other witnesses, Sedway admitted to having known Ben Siegel, Meyer Lansky, Jack Lansky, Little Augie Casanno, Frank Costello, Joe Adonis, Nate Rutkin, Frank Erickson, Longie Zwillman, Charles “Lucky” Luciano, Charlie Fischetti, Rocco Fischetti, Jack Dragna, Gene Normile, Jake Guzik, and the principals in the Cleveland group. He knew Hank Greenspun, but not under his birth name of Herman. He denied having ever had a business relationship with any of them or knowing any specifics of their business. Nor did he know whether Siegel had the race wire in Los Angeles or not.

Sedway then talked about his partnerships with Siegel in the Golden Nugget and Frontier Club race books, but, when pressed about Siegel’s outside interests, objected that “Siegel wasn’t the talkative type. If I wasn’t interested in a business, he didn’t discuss that business with me.” After Tobey went on an extended diatribe that culminated with him calling Sedway and his partners “a cancer spot on the body politic,” the senator returned the floor to Halley, who continued questioning Sedway — in less judgmental terms — about his current businesses and his knowledge of the business of Lansky, Sadlo, Costello, Dragna and Hymie Levin, about which he claimed to know nothing. He was similarly uninformed about the reasons for Siegel’s murder. After estimating that the Flamingo produced $400,000 after taxes per year, Sedway was excused.

That led to the day’s final witness, builder and automobile parts store owner Robert J. Kaltenborn, who had pled no contest to tax evasion and served four months in federal prison. Kaltenborn testified that an Internal Revenue Board employee had attempted to shake him down, but couldn’t offer proof. He was afraid of retaliation for testifying, but Kefauver cut him off with a bland reassurance that they probably wouldn’t leave him twisting in the wind (“we will do our best anyway”) before adjourning the committee and convening the final press conference of the day. Kefauver had a plane to catch.

In the end, Kefauver was unable to rouse Congress to action against Nevada’s regime of legal commercial gambling, but in the aftermath of his committee’s investigations public opinion turned against illegal gambling, inspiring crackdowns against illegal gambling operations around the country. Other states considering legalized gambling (including California) demurred, and states with some tolerance of various legal gambling schemes closed those loopholes. Kefauver’s Las Vegas hearings, then, helped provide a cocoon of monopoly for the Nevada casino industry to grow unchallenged for the next 25 years, which likely benefited the state as a whole.

David G. Schwartz is the author of several works of history about Las Vegas, including At the Sands: The Casino That Shaped Classic Las Vegas, Brought the Rat Pack Together, and Went Out with a Bang; Grandissimo: The First Emperor of Las Vegas; Suburban Xanadu: The Casino Resort on the Las Vegas Strip and Beyond; and Roll the Bones: The History of Gambling. He is the associate vice provost for faculty affairs at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Watch the latest from The History Guy on the Kefauver Committee and Organized Crime

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org