The mystery of Lucky Luciano’s ‘invaluable service’ to the country

On the 75th anniversary of the Mafia boss’s deportation to Italy, questions linger over why his sentence was commuted

Seventy-five years ago, Charles Luciano caught a Lucky break . . . sort of.

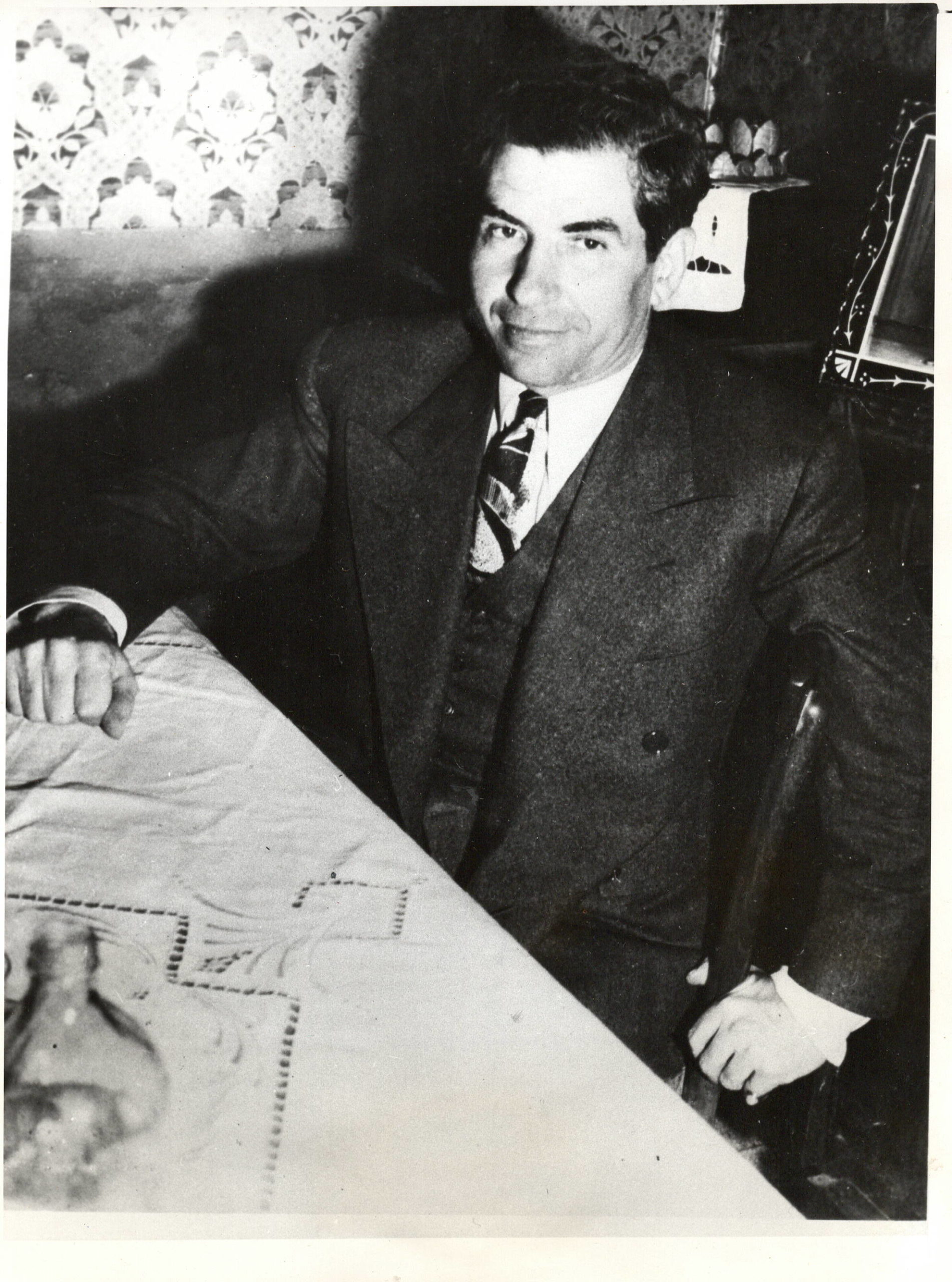

Following several years of negotiations (and under circumstances that still remain a mystery), infamous Mafia boss Lucky Luciano’s fight for freedom had been granted — his sentence was commuted. On Wednesday, January 9, 1946, he was transferred from Great Meadow Prison in Comstock, New York, to Sing Sing Prison, where he awaited the final step of the government’s deal: deportation.

The arrangement had another stipulation, though, something that would draw the mobster’s ire for the rest of his life. The conditions of the deal meant not only immediate deportation to Italy, but Luciano was not permitted to step foot back in the United States — ever.

The lead-up

Prosecutor Thomas Dewey once described Luciano as “the greatest living gangster in America” and “the most dangerous.” During the 1936 trial that put Luciano behind bars, Dewey tailored his case accordingly, right into the public animus toward crime lords, declaring, “Isn’t it time the boss was convicted?”

Luciano and eight co-defendants felt the heavy hand of justice on 62 counts (four others pleaded to lesser charges). Lucky received the harshest punishment on charges of, basically speaking, being head pimp of an extensive prostitution racket.

He was sentenced in June 1936, and he was sent to Sing Sing in July. The stay was short. Following an examination of his psychology and criminal history, it was recommended that Luciano be moved to a facility better suited for inmates with narcotics and/or mental health issues. He was transferred to Clinton Prison in Dannemora, New York, a cold, unwelcoming facility derided as “Little Siberia.”

After six years, Luciano’s dark tide began to turn in his favor. It began in February 1942 when the French ocean liner Normandie caught fire and sank in New York harbor while being retrofitted for naval use. Although the cause of the fire ultimately was a welder’s torch, investigators initially suspected enemy sabotage. The course of events that followed led to an unprecedented relationship between law and outlaw.

Bizarre turn of events

Notwithstanding the expected (and ultimately futile) appeals process, Luciano’s journey to eventual freedom bore elements of a grand spy novel rife with plot twists, wartime espionage, secret rendezvous, paper trail disappearing acts and even some blackmail. The diverse cast of characters included military brass, brazen lawyers, an array of mobsters and, perhaps most interestingly, the crusader who put Luciano behind bars in the first place.

How did it all start? Presumably, fear of Nazi sabotage on U.S. shores led to a clandestine collaboration, through intermediaries, between the Navy and New York’s organized crime network.

According to author Thomas Hunt, here is how it started:

“Understanding organized crime’s control of dock unions, ONI (Office of Naval Intelligence) Captain Roscoe C. MacFall, Commander Charles Radcliffe Haffenden and Lieutenant James O’Malley Jr. sought underworld assistance. They approached Frank Hogan, Manhattan district attorney, and Murray I. Gurfein, assistant D.A. in charge of the Rackets Bureau, seeking an introduction to the Mafia.”

Much of what took place during this collaboration is conjecture, and a lot of documentation relating to it simply vanished. What is known: Following the introduction of military and Mob, meetings were held at the Dannemora prison that included Luciano, Meyer Lansky and other visiting parties. Under the pretense of making these meetings more feasible, and by order of New York State Corrections Commissioner John A. Lyons, Luciano was moved to Great Meadow on May 12, 1942. There, Luciano continued to receive visitors such as Frank Costello, Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel and attorney Moses Polakoff.

Meanwhile, contributing to an already unconventional course of events, August “Little Augie” Del Gracio, a recognized international drug trafficker, pleaded Luciano’s case to George White in May 1943. Del Gracio, claiming he was sent on behalf of Costello, Lansky and Polakoff, wanted to cut a deal for Luciano. White, a narcotics agent and OSS Intelligence man, entertained Little Augie’s discourse only because he had an ulterior motive. The two had a history; they were frenemies, you could say.

Ultimately, though, White did not care about Luciano’s bid for clemency; his primary mission involved testing a truth serum on the unsuspecting guest. After unknowingly ingesting THC (infused in tobacco cigarettes) Del Gracio’s dialogue, much to White’s surprise and glee, veered into an unsolicited, casual and very revealing diatribe on how the drug business worked. At the meeting’s conclusion, White achieved his goal, while Del Gracio was left “high” and dry. We don’t know if Luciano’s friends did or did not sanction Del Gracio’s mission, but it certainly added another offbeat layer to the convoluted historical account.

In May 1945, citing “invaluable service” provided by his client to the military, particularly in regard to the Allied invasion of Sicily, attorney Moses Polakoff filed an application on behalf of Luciano to the state parole board in Albany. The board’s favorable report made its way to the desk of former prosecutor and now Governor Dewey. On January 3, 1946, the governor signed off on the parole. Luciano had served nine and a half years of a steep 30- to 50-year sentence.

“Isn’t it time the boss was convicted?”

Thomas Dewey

“Luciano is deportable to Italy,” read Dewey’s statement. “Upon entry of the United States into the war, Luciano’s aid was sought by the armed services in inducting others to provide information concerning possible enemy attack. It appears that he cooperated in such effort, though the actual value of the information procured is not clear.”

It should be noted that commutation is not a pardon, but rather a reduction in sentence being served, either totally or partially. It has no effect on the individual’s record (doesn’t expunge or alter it), nor on immigration status. Luciano was not a documented U.S. citizen, hence the deportation caveat (and presumably a key factor in the government willingness to offer a deal to Luciano).

Exile to Italy, but not for long

Luciano exited Great Meadow destined for Sing Sing on January 9, 1946. According to an Associated Press reporter, “Luciano arrived at Sing Sing with his fingernails manicured and wearing a jeweled wristwatch and ring. He was accompanied by one prison guard on his journey.”

Authorities then whisked Luciano from Sing Sing to an undisclosed location on Ellis Island. He was placed in a room, guarded and locked from the outside. Luciano spent several days in wait, yet able to receive visitors. Among them was the Prime Minister of the Underworld, Frank Costello. Not allowed, however, were reporters. One brazen newshound attempted to disregard the ban, and found himself physically ejected. When asked why Costello had permission to visit Luciano, Lloyd H. Jensen, chief of the Detention, Deportation and Parole Division, told the press that he personally authorized the visit, adding, “Luciano was here as a deportee, not as a criminal. Like everybody else, he received visitors in a public room with a guard standing by.”

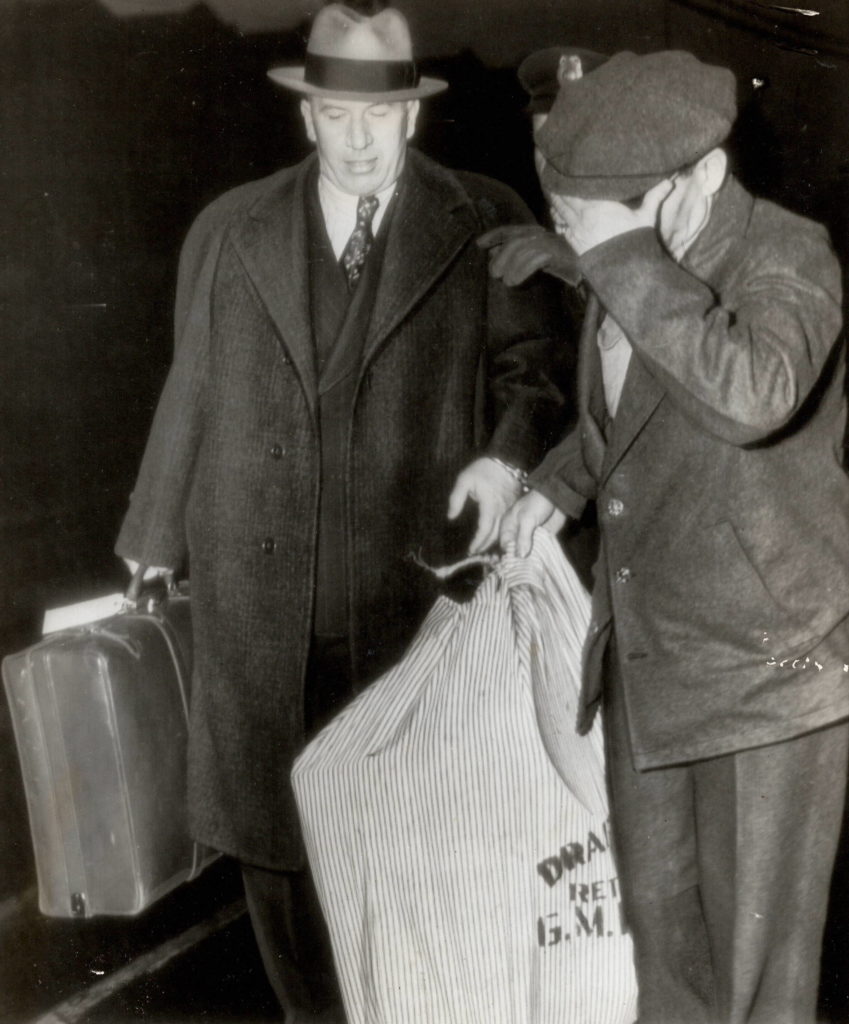

On February 8, 1946, Luciano was taken to Pier 7 in Brooklyn and placed aboard the Liberty ship Laura Keene. Brawny dockworkers kept the curious newsmen at bay, but according to Daily News reporter Art Smith, an entourage of six men led by Albert Anastasia boarded the ship around 8 p.m. What’s more, and take this with a heavy dose of skepticism, the story continued with quoted conversation, allegedly between Anastasia and Luciano, that concluded at 11 p.m. with Luciano delivering a farewell speech. “I’m really glad to be getting out of this country,” he supposedly said. “I will be a free son-of-a-bitch. I will be a free man in Italy, even though I do not intend to stay there long.”Within the annals of organized crime history, truth is often stranger than fiction, but did a single newsman get access to such an intimate conversation? Possible? Yes. Probable? No.

The Laura Keene set sail the next morning. Luciano arrived in Naples on February 28, avoiding the press as much as possible, commenting only that the voyage was“pleasant.”Rumors of “other” travel plans had begun circulating even before his arrival in Italy. Sure, there were the publicly known jaunts Luciano would make to Rome and Sicily, but law enforcement and the press were far more interested in whispers of a trip to Latin America, specifically Mexico.

Luciano hounded by surveillance, press

From the moment he set foot in Italy, Luciano tried to lay pretty low, and dropped out of public view for months. His name finally re-emerged in the same sensationalistic manner as it had back in New York. Stories surfaced alleging Luciano took the reins of a “Robin Hood” band of thieves known as the La Marca Gang, running a human trafficking ring. Gossip columns told of Lucky in Paris, rendezvousing with old flame and former showgirl Gay Orlova. In early September, the New York Daily News broke the story purporting Luciano had acquired passage to Mexico, information allegedly provided by “stool pigeons” within Italy’s underworld. Of all the gangland hearsay, that one turned out to be somewhat accurate. That October, Luciano made his way to Cuba via South America — but that is another story entirely.

Incidentally, agents of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, already present in Italy, had been keeping track of Luciano’s movements. FBN agents, the American consul and the Questura, initially tasked with keeping an eye on self-exiled fugitive Nicola Gentile, passed confidential memos up the chain, referencing directives “concerning persons guilty of violation of narcotics law” of which one in particular, dated July 31, 1946, specifically mentioned “Charles Lucania.” The surveillance operation undoubtedly contributed to, if not initiated, a relentless campaign that FBN Commissioner Harry Anslinger set in motion the following year and waged against Luciano until, literally, the day the Mafia don died.

As for Thomas Dewey, he drew criticism for signing off on the Luciano deal. Despite the inquiries, Dewey remained tight-lipped on details outside of very minimal and scripted statements concerning the gangster’s assistance in war efforts.

Perhaps Luciano’s version of the entire process, which he divulged to sports columnist Oscar Fraley during an interview conducted in 1960, leans closer to the truth about how things get done in the underworld.

“You know how I got out?” Luciano asked. “This is the truth. I told my lawyers to get everything they could on a certain man. They had a book full of stuff. Then my lawyer walked in and threw it on his desk, and told him if I wasn’t deported, anything to get out of prison, this would be made public information.”

Luciano hissed a parting shot: “They think I was bad, they should’ve seen what we had on him, this honorable pubic servant.”

Christian Cipollini is the author of Lucky Luciano: Mysterious Tales of a Gangland Legend and Murder Inc.: Mysteries of the Mob’s Most Deadly Hit Squad.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org