Separating fact from fiction on the Flamingo Hotel’s 75th anniversary

Movies and legends have skewed the public understanding of the resort’s grand opening

Much of what Americans know about Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel comes from watching the 1991 film Bugsy. That certainly applies to the general view of the opening of the Flamingo Hotel in Las Vegas on December 26, 1946. In the film’s portrayal of the event, there are virtually no guests, and a powerful thunderstorm strikes, knocking out the power to the casino. Warren Beatty, who plays Siegel, announces that the Flamingo will close the following day. While certainly influential, Bugsy is not the only source to depict the Flamingo’s opening as a disaster. One sees the failure in the 1974 HBO film Virginia Hill: Mistress of the Mob, which featured Harvey Keitel as Siegel, and in novels such as The Vegas Legacy (1983) by Ovid Demaris and Sin City (2002) by Harold Robbins. Similarly, in Las Vegas: A Desert Paradise (1986), Las Vegas historian Ralph Roske said the opening drew “small crowds.”

The reality was strikingly different. First, there were no powerful thunderstorms in Las Vegas. There was heavy rain in Southern California, and six inches of snow fell on Mount Charleston, but the weather bureau at McCarran Field reported no thunderstorm and only 0.12 inches of rain for Las Vegas. To be sure, the West Coast storms grounded flights, which kept Hollywood celebrities from participating in the first night’s activities, but that was not terribly important because the third night was the one dedicated to having celebrities. While some of the promised big names such as William Holden, Lucille Ball and Ava Gardner did not appear, there were still recognizable Hollywood figures present on the evening of December 28. George Jessel served as master of ceremonies and introduced Eleanor Parker, Charles Coburn, George Raft, Vivian Blaine, George Sanders, Lon McAllister and Sonny Tufts, not only to those in attendance at the Flamingo, but also to a nationwide radio broadcast that originated from Las Vegas station KENO.

Second, for the special three-night grand opening — two dedicated to residents and then the third focused on the celebrities — the Flamingo was packed. On opening night there was a traffic jam at the entrance to the parking lot, and, according to travel writer Roland Hill, when they opened the doors “it was like the rush of olden days on to the newly opened lands of the West.” Louis Wiener Jr., Siegel’s lawyer, recalled, “You couldn’t get in with a shoehorn. Everybody was there.” In his article on the opening, Wally Williams wrote in the Las Vegas Review-Journal, “It appears the proprietors will have to disjoint the walls to take care of the mob.” Columnist Walter Winchell reported that in the first three nights the Flamingo attracted 28,000 people.

Third, rather than the frustrated and concerned Ben Siegel as Warren Beatty portrayed him, Bugsy was actually upbeat, greeting guests wearing a black tuxedo with a pink carnation. His mistress Virginia Hill attended each of the first three nights, with a different hair color each evening — platinum blond, jet black and then her natural red. There was a floor show featuring popular comic Jimmy Durante, the Xavier Cugat orchestra, singer Rose Marie and dancer Tommy Wonder. Rose Marie recalled that at the end of the show “everyone was standing and yelling.” It was “one helluva night.” Texas gambler Benny Binion, who had recently arrived in Las Vegas, remembered opening night as “the biggest whoop-do-do I ever seen.”

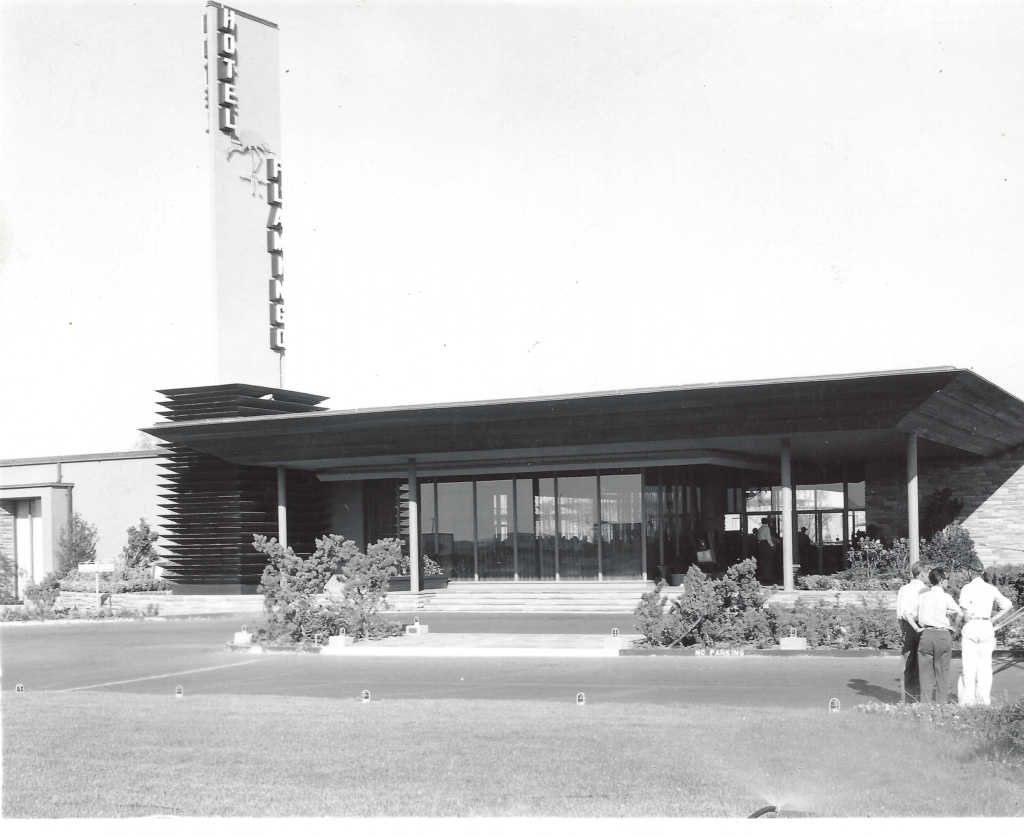

The opening festivities took place in a type of casino no one in Las Vegas had ever seen. Dealers and guests later described the Flamingo as “posh,” “ritzy” and “elegant.” Thelma Coblentz recalled “knee-deep carpeting and elegant draperies and beautiful dinner service.” And then there were the flowers, “truckloads” of them, “in the shapes of wreaths, horseshoes and in baskets.” After surveying the scene, Jimmy Durante walked up to Siegel and exclaimed, “Benny, da place looks like a cemetery wid dice tables and slot machines.” One columnist in attendance wrote about the large bar, which was “full of mirrors, green leather walls, a black ceiling and tomato red furniture.” The approach to the casino also impressed visitors. According to the Las Vegas Age, guests walking from their cars saw “a forest full of evergreens,” palm trees and “semi-tropical shrubs.” Besides the large spotlights in the sky, they saw the shrubs lit up in bright blue and red colors.

Entertainment columnists wrote glowing accounts of the three opening nights. Jimmy Starr called the Flamingo a “magnificent spa,” an adult’s “fairyland,” with buildings and landscaping that were “lush, plush and fantastic.” Starr concluded that the Flamingo was “the most fantastic gambling casino . . . ever constructed.” Aline Mosby agreed, writing that this “junior size Taj Majal” was “the world’s most super-colossal saloon.” Bob Thomas described a casino that looked “like a set that M-G-M wanted to build but couldn’t because of budget limitations.”

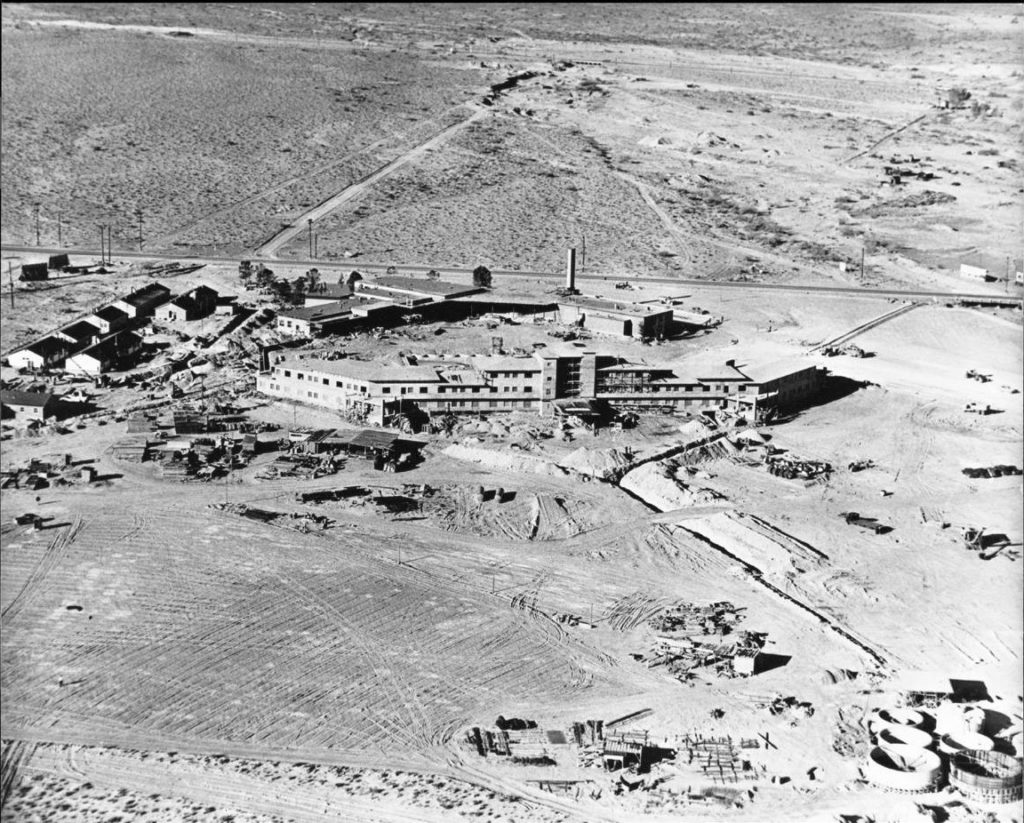

Despite all the hyperbole over the opening, Siegel faced serious financial challenges. He had yet to raise enough money to cover the construction costs that had escalated from an original budget of $1.2 million to about $5 million, a figure that would continue to soar with the completion of the hotel rooms in February. An FBI memo indicated that the “patronage” at the Flamingo “was large but not lucrative.” Observers at the opening claimed hundreds of thousands of dollars were gambled. As Wiener remembered, “there was so much money you couldn’t believe it.”

Yet the Flamingo casino was not the big winner. As Wiener claimed, “If they had dealt lucky the first few days they were open, they would have won the cost of the hotel.” Opening the Flamingo before the hotel was ready for occupancy was part of the reason for the losses. Rather than continuing to play at the tables, many winners left to stay at the El Rancho Vegas and the Hotel Last Frontier. The losses continued into the following month. An informant told columnist Dorothy Kilgallen, for example, that the famed gambler Nicholas “Nick the Greek” Dandolos won about a half-million dollars in four nights at the tables during the second week of January. Scams by the croupiers at some of the tables made matters worse.

After the novelty of the Flamingo waned, fewer local patrons made their way to the new casino. Rose Marie recalled, for example, that after the big opening nights, it was not uncommon for Jimmy Durante to perform in front of fewer than two dozen people. When new acts such as Lena Horne opened, the crowds came back, but then would dwindle once more. Siegel cut wages and poured more of his own diminishing bankroll into the property, but the losses continued and triggered an ominous rumor. An informant told an FBI agent that Siegel told him that Joe Adonis, Frank Costello and his old friend Meyer Lansky “may want to kill him” for losing the money they had invested. In the wake of all these troubling developments, Siegel announced that the Flamingo shops, restaurant and casino would close on February 6 and would not open again until the hotel rooms were ready on March 1.

The response to the opening of the hotel was as enthusiastic as it had been for the casino. Designed by Las Vegas architect Richard Stadelman and Los Angeles interior designer Tom Douglas, the 100-room Flamingo, according to Douglas, would be hailed as “the most luxurious hotel in America.” It featured green carpeting, a large Lucite chandelier in the lobby, and the rooms had green, yellow, lime or pink draperies and wallpaper. Each bedroom included handmade beds, Venetian glass ashtrays and green leather wastebaskets. In all, Douglas claimed the total cost of furnishing each room was about $3,500.

Columnist Erskine Johnson said that the “swanky” hotel looked “like an M-G-M movie set,” all in “flamingo pink, pale lime chartreuse and palm trees.” Bob Considine wrote that the hotel was “built apparently from blueprints taken from a chorus girl’s dream of heaven.” Ed Sullivan informed readers that he had heard the new hotel “is out of this world,” and Malcolm Bingay spoke for most in concluding that with the completion of the hotel portion of the property, “Bugsy reigns supreme in all his grandeur.”

The glorious publicity did little to stop the financial challenges for Siegel, however. Two of his checks totaling $150,000 to Phoenix builder Del Webb bounced. He tried all sorts of things to improve revenue. The Flamingo began hosting small conventions, and his publicist Hank Greenspun promoted the hotel with special buffet nights, afternoon bingo games and drawings for cars to attract more gamblers.

Although he completed both the casino and hotel, Siegel did not get to see the success that the Flamingo enjoyed shortly after his murder on June 20, 1947 in Beverly Hills. The Flamingo became the model for the successful Las Vegas hotel-casinos of the 1950s with luxurious accommodations, big-name headlining performers and an array of gambling options.

Larry Gragg is Curators’ Distinguished Teaching Professor Emeritus at Missouri University of Science and Technology where he served as chair of the history and political science department for 17 years. He is the author of 10 books, including Bright Light City: Las Vegas in Popular Culture (2013); Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel: The Gangster, the Flamingo, and The Making of Modern Las Vegas (2015); and Becoming America’s Playground: Las Vegas in the 1950s (2019).

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org