Hanley enjoyed winning streak in criminal courts

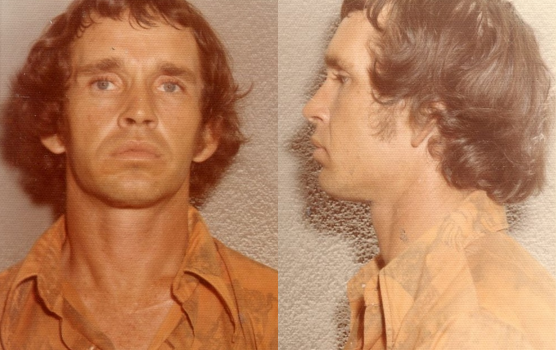

Part 3: Gramby hired to bomb non-union restaurants, casino

Listen to this article.

Read the series: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4

Third of four parts.

Just before his planned murder trial in the Ralph Alsup slaying, Tom Hanley caught another astonishing break. On March 30, 1970, county prosecutors requested dismissal of the charges. They pointed to insufficient evidence. Two important witnesses, Alphonse Bass and Marvin Shumate, were dead, and the two others – Michael Marathon and former Hanley aide Barbara Simmons – were not credible enough to secure a conviction. Officially, Alsup’s murder remains unsolved.

This put Hanley on a hot streak. Three weeks later, a judge, finding that no crime had been committed, dismissed the criminal libel and extortion charges filed by the Nevada Club in state court. All that remained was the Nevada Club federal extortion case. In May, while walking by the Four Queens casino downtown, a passing citizen smacked Hanley in the mouth and ran away. No one was arrested. In June, a judge granted Hanley’s motion to change the venue of the remaining extortion case to California.

As for career criminal LeRoy Marsh, he agreed to submit to a lie detector test and plead guilty to the armed robbery of a Las Vegas tavern. In exchange, the district attorney dismissed his murder charge in the Bass case. The judge sentenced Marsh to five years in state prison. The Bass homicide ended up the same as Alsup’s, never adjudicated by law enforcement.

Wendy Mazaros stated in her book that Tom confessed to murdering Alsup and Shumate. Their cases stood, he said, “with no small measure of pride, as examples, of his intellectual dominance over police, over attorneys, over anyone who ever tried to outsmart him.”

Things also worked out for Hanley in federal court in Los Angeles. He pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor, avoiding a felony conviction and prison time, in the Nevada Club extortion case. In Las Vegas, a federal judge ruled prosecutors denied Hill a speedy trial and dismissed his charges.

Now free of criminal cases, and ready to unleash his vindictive streak, Hanley filed another flurry of lawsuits against his detractors. In October 1970, he argued for an award of $300,000 in damages, alleging libel against the owner of the Nevada Club and the Oakland Tribune. The newspaper in 1969 published a 12-part series on him and the AFCGE, which he said falsely stated the union engaged in “shakedowns” and “sweetheart deals.”

In April 1971, Hanley filed a $1.75 million action against the Fremont Hotel and four men, including former District Attorney George Franklin and City Attorney Earl Gripentrog, saying they tried to destroy the AFCGE by promoting charges that Hanley conspired to murder Alsup and that they induced a casino dealer to provide false testimony against him.

His next suit asked for $3.7 million from the Hacienda hotel and county criminal prosecutors, declaring that they tried to use the Alsup case to ruin the AFCGE. In August, he filed yet another damage suit against the Nevada Club, Franklin and Gripentrog, this time for $500,000. In 1972, reopening old wounds, he filed a $1.65 million suit over his 1954 expulsion by the International Sheet Metal Workers.

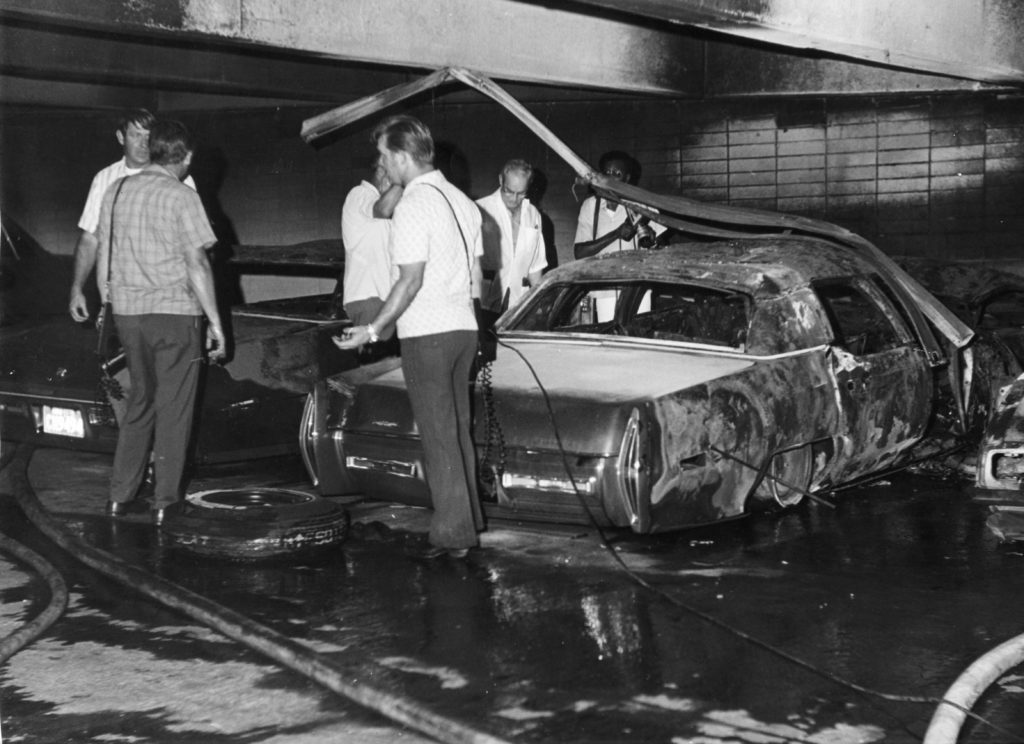

Coulthard car bombing

On July 25, 1972, at 3:40 p.m., in the parking garage of the Bank of Nevada building in downtown Las Vegas, lawyer and former FBI agent William Coulthard entered his car. A clothespin attached to wiring in the car’s steering column detonated a powerful bomb fixed beneath the engine. His body was blown to bits. Investigators identified him via dental charts. Five cars beside Coulthard’s also burned. The blast blew a hole in the concrete floor. The bombing happened after Coulthard refused to sell his interest in land under Benny Binion’s Horseshoe casino. Binion later signed a 100-year lease on the land.

Despite federal investigations and a reward of $75,000 offered for information resulting in an arrest and conviction, no one was arrested in the deadly bombing. Although it cannot be proved, Wendy Mazaros, in her book, stated that she witnessed Gramby Hanley accepting responsibility for planting the explosives that killed Coulthard, at the behest of Binion. Tom Hanley, she said, remarked that Coulthard tried to “extort” Binion. “So he had to go,” she quoted him saying, “We blew the son of a bitch up.”

Hanley then considered starting a new sheet metal workers union, specifically for housing developments. He sensed an opening when his old union Local 88 appeared divided during its protracted strike in 1972. Nothing came of it. His next big move, in 1973, was another lawsuit, this time against Sheriff Lamb and District Attorney Franklin, for $500,000 in personal damages from his criminal cases.

Little is known about what came of most all of Hanley’s “revenge” lawsuits: if he lost, settled out of court or something else. Newspapers wrote about just one of them progressing. In December 1971, a California court dismissed his Oakland Tribune libel suit, but in 1975, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, reasoning the case deserved to be tried in Hanley’s domicile of Nevada, not California, reversed the ruling and sent it back to federal court in Las Vegas. However, the case remained dormant. Maybe Hanley had had enough after years of litigation and legal expenses.

Hanley, still an experienced sheet metal technician, founded a business with a lot of potential customers in Las Vegas – air conditioning. From his friendship with Bramlet, the Culinary became Hanley’s biggest client. He built and maintained the AC system at the union headquarters.

Bramlet orders restaurant, casino bombings

During Bramlet’s two decades at the helm, Local 226’s paid membership grew dramatically, from about 1,500 to 23,000 in 1977. It was the largest union in Nevada and the second largest local in the country. Nevertheless, by the mid-1970s, Bramlet became frustrated by intractable owners of large restaurant “supper clubs” in Las Vegas and hotel-casinos in Northern Nevada that refused to sign or renew employee collective bargaining pacts. His most determined foe was Hershel Leverton, owner of Alpine Village, a popular Bavarian-German eatery that first opened in 1951 and relocated several times in the Las Vegas area. Leverton and a partner bought it in 1958 not intending to sign with the Culinary. The day Leverton opened, Bramlet “came out of the blue and said we had 15 minutes to join or he’d put me right out of business,” he told the Los Angeles Times in January 1976. “‘Take your best shot,’ I told him, and 15 minutes later 20 pickets started marching.”

In a court battle, Leverton initially won a restraining order in December 1958 but the judge allowed Culinary picket lines to remain outside, and they did – over the next 18 years. Leverton endured, unbowed in the face of multiple acts of intimidation. “They’ve tried everything,” he told the Times. “Sugar in the gas tanks, stink bombs … sabotage threats. You name it. You just don’t kiss and make up after all that.”

Pressure on Leverton from the Culinary leadership amplified beyond measure in 1975. Unknown at the time, Bramlet, hoping to frighten the business into agreeing on a union contract, paid Gramby Hanley to position an explosive at Alpine Village, located on Paradise Road across from the Las Vegas Hilton.

Bramlet also hired Gramby to help solve the union’s organizing problems with three hotel-casinos at South Lake Tahoe: Harvey’s Wagon Wheel, the Sahara Tahoe and Harrah’s. Gramby wrote off Harrah’s as too risky. Security guards ran Gramby off as he tried to install a bomb at Sahara Tahoe.

Gramby decided to set up bombs at Harvey’s and Alpine Village on the same day. The one at Harvey’s exploded first, at 1:27 a.m. on September 1, 1975. An outbuilding with the hotel-casino’s air-conditioning unit had minor damage, as parts of the bomb failed to explode. There were no injuries and the casino remained open. Someone phoned Harvey’s about two other bombs but detectives found nothing.

The younger Hanley quickly drove back to Las Vegas to ignite the bomb he hid at Alpine Village. But he bungled the job. Later that day, an explosive inside a paint can about 30 feet behind the Alpine blew up and only damaged a water cooler and former employee locker. A plastic explosive and two smoke grenades – presumably to send smoke into the building – tied to an air conditioning unit failed to explode. While maybe meant to serve as a warning, Alpine Village managers did not budge.

He tried again at the supper club on Saturday night, December 20, 1975. This time he chose potent charges of TNT in two bombs, which he threw onto the roof. With about 350 dinnertime patrons and 70 employees packed inside the business, the two explosives detonated 30 seconds apart. Everyone inside evacuated but no one was hurt. The bombs started a fire on the roof with flames 20 to 30 feet high. The blast moved downward, leaving a pair of two-foot holes, throwing debris into the kitchen. The Culinary Union issued a statement disavowing any role. Who planted the bombs confounded law enforcement.

Three weeks later, Gramby made out better. A stronger explosion rocked another non-union restaurant, David’s Place on West Charleston Boulevard. The early morning blast on January 12, 1976, came from a few bombs triggered simultaneously, nearly destroying David’s and damaging four neighboring businesses. David’s was closed at the time, but paramedics took 14 elderly tenants of a residence hotel next door to a hospital for observation. David’s had also avoided a union deal with the Culinary and again suspicions focused on the Culinary, but deputies made no arrests.

After the David’s Place bombing, both Tom and Gramby laid low for a while in 1976, but that soon changed drastically. Bramlet, joined with Culinary bargaining partner Bartenders Local 165, ordered strikes at major hotel-casinos on the Strip to press them to renew expiring contracts. The strikers discouraged customers, and the hotels bore more than $20 million in lost revenue. Bramlet also directed members to strike prominent supper clubs in Las Vegas that had not approved four-year agreements ending in October. About 30 of 50 supper clubs did renew their pacts. The Culinary assigned picket lines at the other clubs. In November, the Peppermill, Bootlegger and Copper Cart clubs voted to decertify, or drive out, the unions. Two others, Starboard Tack and Village Pub, asked the NLRB for votes allowing employees to represent themselves with “in-house” unions. In early January 1977, the board accepted the Starboard Tack and Village Pub requests, setting January 27 for Starboard’s election.

Bramlet, seeing his leadership imperiled by lost elections and possible decertifications, became desperate again. A little more than a year after the bombing of David’s, Gramby would plant even more potentially devastating, fire-type bombs at the restaurants seeking elections.

Just before 11 p.m. Sunday, January 23, 1977, a security guard at the Village Pub on Koval Lane noticed gas dripping from a Jeep in the parking lot. He helped evacuate people from the business and a few Culinary members picketing outside. A Las Vegas firefighter answered the call. Fire officials initially figured it was a routine, gas wash chore to rinse away the flammable liquid. But from a quick look inside the Jeep, the firefighter saw behind the front seat a 55-gallon barrel with a hose leading from it to a hole in the floorboard. It turned out the hose extended under the vehicle to the rear and connected to a 12-volt battery with a toggle switch, a safety fuse and a nine-inch tube containing a type of powder. He called in explosives experts.

Minutes later, a similar report came from Starboard Tack on Atlantic Avenue, also picketed by the Culinary. Another Jeep parked there contained the same oil drum gadget. An assistant fire marshal arrived and while attempting to disarm the bomb early Monday, the secondary detonator exploded, burning his hands and abdomen. He was treated and released from a hospital.

In both cases, Gramby had filled each barrel with highly flammable gasoline. He made sure to saturate the insides of the Jeeps and the ground outside them with the liquid. He primed the bombs to detonate once someone activated a “booby trap” by opening the vehicle’s only unlocked door, which pulled an attached wire leading to a spark-producing friction device meant to ignite the spilled gas and then the drum. He added a secondary fuse on each in case the other failed. Either firebomb could have led to a massive, deadly blast. However, owing to flawed detonators, both proved to be duds. Gramby later said that he deliberately set the bombs not to blow, only to frighten people, but given the dangerously high amounts of gasoline, investigators weren’t so sure.

Police learned that someone stole both Jeeps from the lot of a dealership on Eastern Avenue and affixed filched license plates to them.

The successful and attempted bombings in Las Vegas remained a mystery at first. Bramlet felt the heat as a logical suspect. He also endured defeat at the two supper clubs. Days after the discovery of the Jeep bombs, employees at Starboard Tack and Village Pub voted to decertify his union and organize in-house. Workers at seven Denny’s restaurants requested decertification elections as well. The Culinary and Bartenders in mid-February filed appeals with the NLRB against Starboard Tack’s election and the request by Denny’s outlets.

Bramlet disappears in Las Vegas

Labor trouble for Bramlet persisted in Northern Nevada, where his campaigns had struggled with workers for years. Union employees at the Harold’s Club hotel-casino were to hold hearings on whether to decertify Reno-based Local 86 hotel and bartender unions. Bramlet took a flight north to oppose the effort. The vote was a heartbreaking 134 to 134, meaning decertification. He left on a return trip to Las Vegas on Thursday afternoon, February 24, 1977. He phoned his daughter from McCarran International Airport and said he would be home in half an hour. Then he disappeared. His car was located in the airport lot the next day.

As Las Vegas police and the FBI investigated the union’s missing persons report, details trickled out on the hours before Bramlet’s disappearance. While back in Las Vegas, he had made a call to Sid Wyman, an executive at the Dunes Hotel, and asked him to take $10,000 in cash, go to the Horseshoe casino and deliver the money to Binion. Bramlet said he needed the cash for “personal reasons.” The money made it there but Binion said Bramlet never showed up.

Many people called in tips to police, but one source told a detailed and damning – for the Hanleys – story about what happened to Bramlet. The confidential informant was Clem Vaughn, Tom Hanley’s old 1950s Sheet Metal Workers Union hack who remained his close pal for more than 20 years. Vaughn knew what he was talking about. He passed two lie detector tests. Police also interviewed Vaughn after treating him with a “truth serum.”

Vaughn related that he came along that Thursday afternoon with Tom and Gramby. The younger Hanley was angry with Bramlet for not paying him the $10,000 he had promised for the bombs at the Village Pub and Starboard Tack. Bramlet declined to pay since they failed to work. Somehow, the Hanleys knew when Bramlet would make it back in Las Vegas, and where he parked his car in the airport’s lot. They determined to kidnap him and force him to pay up.

Tom and Vaughn drove up in a rented van. They encountered Bramlet as he made his way to his car. Gramby, Vaughn recounted, stepped forward and pointed a handgun at Bramlet and threatened to shoot him then and there if he did not enter the van. Bramlet got in, and agreed to arrange for delivery of the $10,000. They handcuffed Bramlet and gagged him with tape. Finally, in the rear of the van, Vaughn said he watched as the inebriated Tom called out Bramlet’s name. When Bramlet turned to face him, Hanley shot him in the chest with a .22-caliber handgun. Tom Hanley later admitted he had consumed five half-pints of Wild Turkey bourbon whiskey before firing.

Gramby would tell a bit more to the U.S. Senate staff in 1982. After forcing Bramlet into the van, they first drove to Goodsprings, west of Las Vegas, where Tom phoned the Dunes. Then they drove to Mountain Springs and Bramlet made two pay phone calls to the Dunes. After, they wheeled down a desert road where he said Tom and Vaughn stated they could not bring Bramlet back to town alive. Gramby exited the van. He saw another car drive up and shut off its lights. At that, he gave up on Bramlet, got into the front of the van and soon heard the shots.

What had gone on in Tom’s drunken mind? Was he, as Gramby maintained, a paid hitman for Chicago? Did he resent Bramlet over the $10,000, some of which he would skim off from Gramby as he had Bramlet’s other payments? Or did he feel power over the now-helpless Bramlet, who succeeded as a labor leader for 25 years, way beyond Hanley, who, mostly through his own faults, had failed with the sheet metal workers and the ill-fated AFCGE? Or was it because Bramlet quashed his idea of reviving the gaming employees union?

Bramlet represented what Hanley wanted but never had. Both men were 60 years old, Tom eight months older. For years, as head of Nevada’s largest union, Bramlet negotiated contracts with the giant Strip hotels. Bramlet was president of the state AFL-CIO. Hanley just ran an air conditioning company, employing himself, Gramby and Vaughn. Hanley fixated on a $1,500 debt Bramlet owed for the revamped Culinary AC system. Vaughn would say that Bramlet already told Hanley he’d get his money by February 25, the next day.

Tom must have been filled with hate, spurred by the pints of Wild Turkey, from the number of shots fired. Bramlet had six bullet wounds, one in the sternum, three near his heart and one in each ear. Gramby stripped Bramlet of his jewelry and clothing. In the dark of night, they carried the nude body about 50 feet out to behind a yucca plant. They dug a shallow grave and buried him under rocks. Tom and Gramby retained the jewelry and much of Bramlet’s clothing, perhaps as souvenirs.

Vaughn, the crucial informer and witness, said it was too dim that evening for him to pinpoint exactly where they placed Bramlet’s body. Authorities searched for nearly three weeks in the area he described with no luck. But on March 17, a woman hunting for rocks with her husband came across what looked like a grave. When the man went to investigate, they spotted a human hand jutting out. Bramlet’s body rested there, partly decomposed after three weeks. When authorities reached the grave, compacted stones and dirt on Bramlet’s face made it hard to identify him.

Vaughn urged police to contact Tom and Gramby. Tom’s phone records showed he called Bramlet several times leading up to February 24. Gramby bolted from town soon after the murder, but Tom stayed. Each time detectives interviewed Tom in Las Vegas, he denied knowing anything about Bramlet’s demise. But when mentioned as a suspect in a local news story, Tom fled.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org