The Las Vegas misadventures of Russian Louie

Underworld figure Louis Strauss’s first scam in Las Vegas did not go according to plan, and neither did his last

By the time he was 11 years old, he was arrested for burglary in San Francisco. By the time he was 21, his rap sheet included assault with a deadly weapon. By the time he was 31, he had run his first gambling scam in Las Vegas. By the time he was 41, he was charged with the murder of his partner in a Lake Tahoe casino. And by the time he was 51, he had been dead for more than a year.

He was Louis Matthew Strauss, aka “Russian Louie.”

On April 16, 1953, Strauss got into a Cadillac convertible near his Las Vegas home at 209 North 15th Street. “Russian Louie” has not been seen since.

Strauss spent most of his adult life on the dark side of gambling in California and Nevada, with the occasional visit to Florida. In the late fall of 1934, as he was getting ready to celebrate his 28th birthday, Strauss and a couple of his pals developed a scam to rip off a Las Vegas gambling club.

Nevada banned gambling in 1910. Over the next two decades, some games of chance were legalized, from slot machines to poker tables. In March of 1931, the state relegalized most forms of gambling, moving the craps tables and roulette wheels from the back room to the front room.

But Las Vegas did not embrace the opportunity to expand its gambling economy right away, despite the fact that Hoover Dam construction had brought thousands of workers and their paychecks to town. In the fall of 1934, only 39 slot machines were licensed in the city of Las Vegas. Moreover, 27 of those licensed slots were scattered around the city in retail outlets such as grocery stores and restaurants.

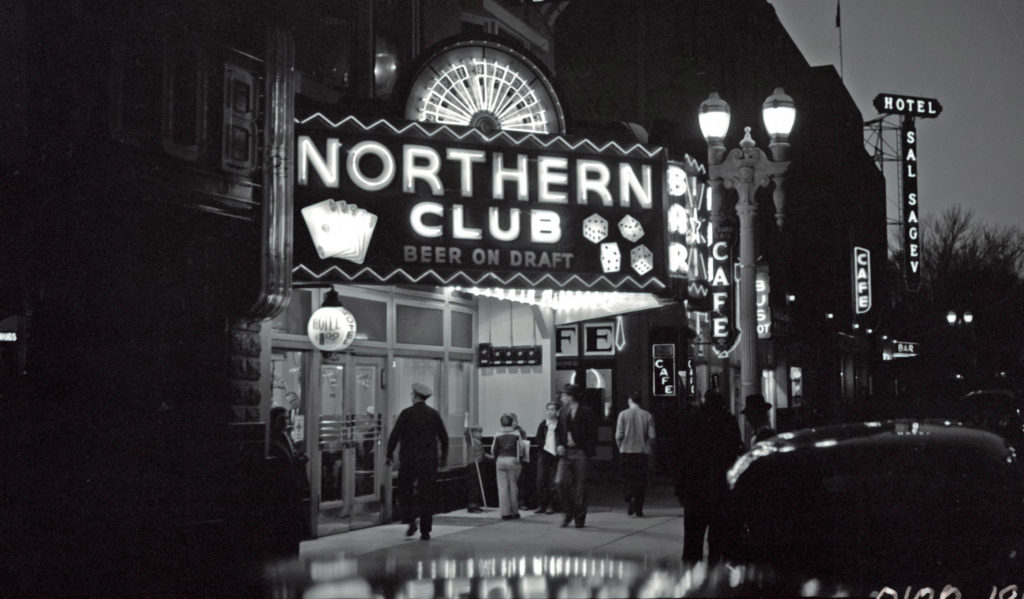

There were only five full-fledged gambling clubs on Fremont Street: the Apache Casino, the Big Four Club, the Boulder Club, the Las Vegas Club and the Northern Club. The largest was the Boulder Club, with its five slot machines, three card games and four devices, including a roulette wheel and crap tables. The Big Four Club was at the bottom of the list, with just one poker table, a roulette wheel and two dice games.

In the middle was the Northern Club with three slot machines and three card tables, which offered both blackjack and poker, along with four “devices,” including craps tables and a roulette wheel.

Plus, the Northern Club was about to start taking bets on horse races at tracks outside Nevada. At that moment, it would be the only race book in Las Vegas. The club’s operators, Dave Stearns and Elmer Sorber, promised patrons they would be able to “hear the description of the races just as if you were at the track.”

On October 4, 1934, a Thursday afternoon, the Northern Club and all gambling operations that applied and paid their license fees were formally approved by the Las Vegas City Commission to operate for the rest of the year.

At this exact moment, Russian Louie and his crew made their move. After reviewing all the operations in town, they decided to target the Northern Club. Their plan was simple. Send in one man, a card dealer by the name of Charles Hall (also called Howe).

On the morning of October 4, Hall offered Stearns and Sorber an arrangement that was hard to turn down, and they didn’t. He would take over one of the club’s already licensed card tables and deal faro. Once one of the most popular card games, faro slipped when it was revealed how easy it was for the clubs to set up the decks so the house would win.

Sorber and Stearns liked Hall’s plan, which included each group putting up $1,000 to bankroll the game.

The second member of the crew, identified at this point as W.A. Burns, walked into the Northern Club and began to play faro at Hall’s table. In a matter of minutes, Burns began winning, and winning big.

Sorber and Stearns had a “lookout” watching the new dealer and quickly reported, “Something is wrong with the game.” By the time Stearns arrived and ordered the game closed, Burns had won $3,200 in just three hands.

After a face-to-face discussion with Stearns, Burns left with only $800 of his $3,200 alleged winnings. Burns said Stearns had promised he would receive the rest of his winnings the next morning.

When Burns showed up, he said Stearns offered him another $1,200, for a total of $2,000, to settle the matter. Burns said he agreed to the deal that Friday morning, October 5. Stearns said he would raise the money and for Burns to return later.

By Sunday, October 7, Stearns and Sorber concluded they had been ripped off by a well-planned fraud involving three men: Hall, Burns and Louie Strauss. And through his connections with the West Coast underworld, Stearns learned that Strauss was the California gambler known as “Russian Louie.”

The three California gamblers reached out to one of the city’s leading attorneys, Artemus Ham. Ham advised them not to file a criminal complaint because it could expose all parties to potential problems.

There was another plan of attack. Burns told Stearns and Sorber that unless they paid up, he would ask the city to revoke their just-granted gambling license. There is no formal record of the response from the Northern Club partners, but clearly it was a resounding no.

The city commission’s recessed meeting of October 4 was set to resume at 3 p.m. Monday, October 8. When the commissioners had finished work on the agenda items and opened up the meeting for public comment, Burns stood up and walked to the speaker’s podium, where he publicly called for revocation of the Northern Club’s gambling license.

There are two versions of what took place next.

The official minutes of the city commission list Burns as “Mr. J.W. Byrnes,” who “appeared before the Board at this time and asked that the license issued the Northern Club be revoked on the grounds that the winnings made by the said W.J. Byrnes had not been paid. A number of witnesses were presented to the Board … verifying the non-payment of the winnings and the reason same should not be paid.”

The formal commission minutes fail to describe what members of the press and the public described as a “near fist fight” and an “impending riot.” City staff alerted Las Vegas Police Chief Clint Boggs, who arrived with Officer Dott Smith, and the meeting simmered down to a shouting match.

Burns called Stearns a “welcher.” Stearns said Burns was part of a swindle, and the deal was a “frame-up.” Sorber said it was a “conspiracy” of cheaters.

At this point, Sorber said another man he identified as “Russian Louie” was part of the scam “to take our roll.”

Not surprisingly, Strauss, who was in the audience, objected to being called “Russian Louie” and ran to the speaker’s platform. Those in the audience were sure a fight would take place.

However, with law enforcement visible, Strauss took a deep breath and told the city commissioners that his name was Louie Strauss, not “Russian Louie.” Strauss also denied he was part of any conspiracy and accused Stearns and Sorber of running a crooked club.

At this point things started to get out of hand again.

Mayor Ernie Cragin, with the backing of the police, gaveled the meeting back to order. Hall told the city leaders that he was the faro dealer, and there was nothing crooked about how he dealt the game.

Stearns told Cragin and the commissioners that no gambling club would pay if it was the victim of a coordinated ripoff. The scam crew, Stearns asserted, was made up of Strauss, Burns and Hall.

Burns threatened to take the matter to a criminal grand jury if Stearns did not “pay up.” Stearns ran to the speaker’s podium and confronted Burns, saying, “Go do your best and see what happens.”

Again, Mayor Cragin gaveled the meeting back to order and declared, “It is up to the house to protect their games.”

Since pulling the club’s license was not on the agenda, the city could not take direct action on Burn’s request. However, the mayor and commissioners ended the matter by unanimously agreeing to schedule a show cause hearing as to why Northern’s gambling license should not be revoked.

Stearns and Sorber now had seven days to prevent the closing of the Northern Club.

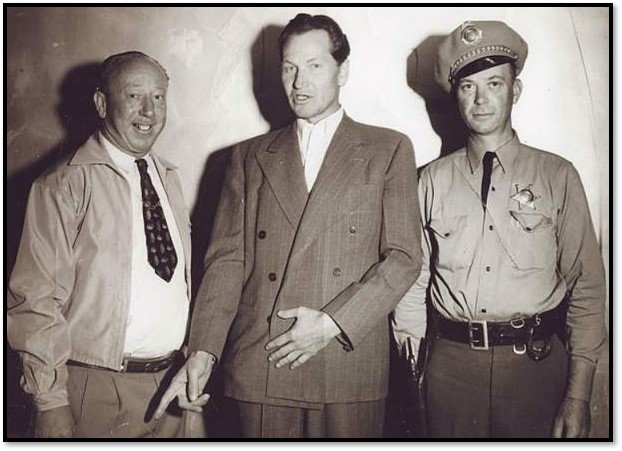

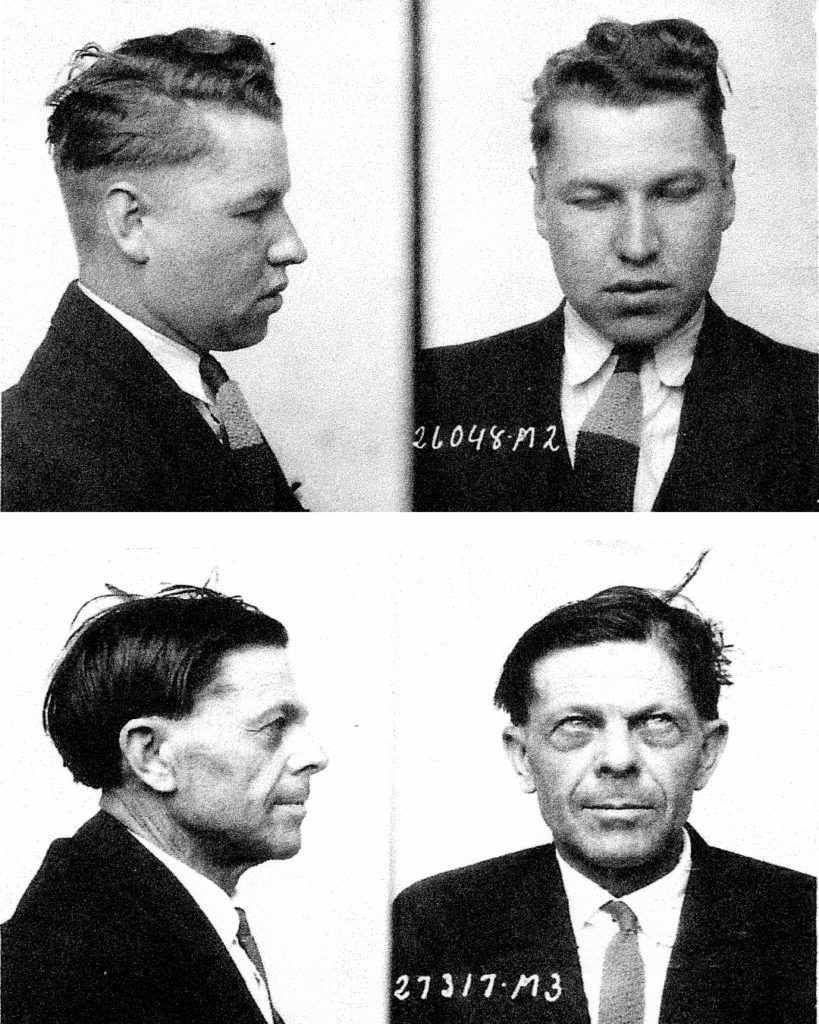

Las Vegas Police Chief Boggs quickly reached out to law enforcement agencies outside Nevada. From California, he received a mugshot of “Russian Louie,” who was formally identified as Louis Matthew Strauss.

Strauss was born in San Francisco on October 26, 1904, to Lithuanian parents. He was not Russian. Strauss’s only connection to Russia was its occupation of the country of his birth and forcing people to speak Russian instead of Lithuanian.

Chief Boggs reviewed Strauss’s rap sheet and found the burglary arrest at age 11. His adult arrest record revealed Strauss faced a series of charges, including grand larceny, suspicion of assault with a deadly weapon, robbery and illegal gambling, all in California.

Chief Boggs also received a mugshot and rap sheet for Charles H. Howe, aka Charley Hall. His arrests ranged from forgery to robbery to illegally possessing a weapon, to most recently, “gambling, Los Angeles.”

As for W.A. Burns, aka John W. Byrnes, he was wanted in Canada for “passing a worthless check.”

As the opposing sides prepared their cases, Charles “Pop” Squires, publisher of the Las Vegas Age newspaper, published an editorial pointing out the problems of gambling. Without naming the Northern Club, Squires stated that “Las Vegas for the past two years has been the target of unfavorable comment” about “our gambling clubs.” Squires said if it is true that a Las Vegas gambling club has refused to pay off a debt by using “unfair tactics” and “unfair means to get their patron’s dollars, it is time that gambling in Nevada ceased.”

Thirty-six hours later, the Las Vegas City Commission held its show cause hearing. Las Vegas’ top attorneys were now on the case. Stearns hired Leo McNamee, and Strauss and Burns were represented by Artemus Ham.

Both attorneys got word that city police had received details about the gamblers’ most recent arrests in California for “gaming law violations.” The attorneys asked the commission to delay the show cause hearing so they could secure more “evidence and affidavits.” The City Commission agreed to delay the hearing for another week.

Both sides did not want another hearing or to move the matter into criminal court. They wanted the case closed privately.

McNamee and Ham met with their clients and quickly arrived at a deal. Money changed hands.

Just as the recessed show cause hearing was about to resume, the attorneys submitted a letter to the mayor. The commission meeting started at 7 p.m. with the mayor announcing that the two sides had reached a deal. With little discussion, the commissioners unanimously approved a motion that the matter should be “considered closed.” The Northern Club kept its licenses.

Details of the deal quickly spread through the town. At the start of the scam, Strauss and his crew wanted the Northern to pay them $3,200. Then the out-of-town hoodlums said OK to the offer of $2,000. In the end, they settled for $1,500.

Minus their initial purchase of $500 in chips to play at the Northern, as well as attorney fees and travel expenses for three weeks in Las Vegas, the gamblers left town with a net profit of a few hundred bucks, split three ways.

It is also likely that Stearns, known for a quick temper, suggested to Strauss and his buddies not to show their faces in Las Vegas again.

As for Stearns, by the end of the year, at least on paper, he ended his involvement with the Northern Club, and Sorber took over.

The two men soon became partners in a new venture in a closed casino. In 1931, the Corneros, bootlegging brothers from California, built and opened the Meadows hotel, casino, restaurant and showroom a few yards outside the city limits. The Meadows resort didn’t pan out as the Corneros had hoped, and by 1934 it was sitting idle.

Stearns and Sorber cut a deal with the Cornero to reopen the Meadows. In early 1935, the two men renamed the resort the “Coconut Grove Meadows.” Stearns’ operation of the Meadows started on a positive note, but by the end of 1935 his bubble dancer had lost all her bubbles.

The Meadows was closed by then District Attorney Roger Foley.

With the Meadows closed, Stearns quickly and publicly returned to operating the Northern Club. His partner Sorber left town to be replaced in 1941 with a new partner. Making his entrance into Las Vegas, New York mobster Benjamin “Bugsy” Siegel became part owner of the Northern Club.

In the 1930s and ’40s, Strauss would find his way into the operation of Lake Tahoe casinos. But in the fall of 1947, Strauss got into a financial beef with one of his partners. He ended up shooting and killing the man. The room was filled with friends, but nobody saw Strauss fire the fatal shot from his .38.

The court ruled it self-defense.

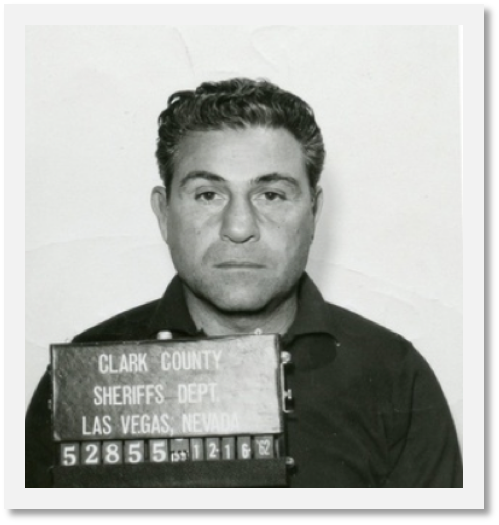

A few months after Siegel was murdered in June 1947, Strauss headed south to Las Vegas. And once again, “Russian Louie” got involved in a scheme to rip off a Fremont Street casino. In this craps table scam, he worked with Allen Smiley — the same Allen Smiley who sat next to Siegel on a couch when he was murdered in Beverly Hills, California.

By now, Strauss had two rap sheets. One was kept by law enforcement and the other by his pals in the crime trade.

On paper and publicly, Strauss built and owned the Fairway apartment complex, which was located behind the Desert Inn hotel-casino.

In the early 1950s, Strauss was considered by a Las Vegas Review-Journal entertainment columnist as “a proud” and “popular man about town” whose apartment complex “is the finest example of modern beauty and good taste.”

On the other hand, a Review-Journal political columnist wrote that Strauss was just “an errand boy for big-time wire pullers.”

As a result of Russian Louie’s lifestyle, he constantly needed money. In February of 1953, he was in a big-time poker game with some of his associates. Two versions of the card game have surfaced. In one, Strauss came out a big winner by cheating and got caught. In the second version, he simply came out a big loser.

In either case, by April 1953, Strauss was looking for funding opportunities.

On the morning of April 16, he got a call from his close friend, Chicago mobster Marcello Giuseppe Caifano, aka Marshall Caifano, aka Johnny Marshall. Caifano and Strauss discussed Russian Louie’s financial problems. Caifano suggested there was a way out, and it could be resolved within 24 hours. Strauss agreed and began packing.

Naomi, his new wife, wanted to know what was happening. He said he was going to the El Mirador Hotel in Palm Springs, and, “Honey, it’s only for overnight, and I’ll be back.” She wanted to know who he was going with. Strauss said even if he told her, “you wouldn’t know them anyway.”

Caifano had told him earlier that he and Jimmy Fratianno would handle the driving of the 260 miles to Palm Springs.

By this time, Fratianno, a Cleveland-bred mobster who relocated to California, had already picked up the nickname “The Weasel.”

Not long before the three men were scheduled to leave Las Vegas, Caifano said he was not going and that Phil Alderisio would take his place. Felix Anthony Alderisio, aka Phil Alderisio, aka “Milwaukee Phil,” was, like Caifano, was part of the Chicago Outfit.

Strauss’ wife said he left early that evening dressed in a rust gabardine suit and rust-colored suede shoes, and he had packed one additional blue-gray suit for his overnight stay in California.

About 5:30 p.m., the three men met at a parking lot near Strauss’ apartment at 209-A North 15th Street.

When Strauss saw Fratianno’s new dark green Cadillac convertible, he knew it would be a good trip. Cadillac’s were his favorite cars. He owned two.

Fratianno told Alderisio to drive as he wanted to take a nap in the back seat. Strauss got in the front seat. After a quick and mysterious stop at the Desert Inn, the three men headed south on U.S. 91 for Palm Springs.

Five hours later, with Fratianno’s help, Strauss, age 48, was dead.

A joke began circulating through Las Vegas within a year of his disappearance. When asked when they planned to pay off a gambling debt, Las Vegans would answer, “Just as soon as Russian Louie gets back!”

Strauss’s body never surfaced.

Why was Strauss killed by his fellow associates? Was it because he cheated at poker with the wrong people, or because he tried to scam Benny Binion (which Binion denied)? Or were there just too many entries on the rap sheet kept by his fellow hoodlums?

Like Strauss’s current location, the reason or reasons why he was murdered may never be known.

But maybe the prediction of Jack Barlow will come true. At the time of Russian Louie’s disappearance, Barlow was chief of detectives for the Las Vegas Police Department. Barlow guessed that Strauss died a horrible death and that “someday we’ll find a skeleton in a desert grave or at the bottom of a bay or river and the mystery of ‘Russian Louie’ will be solved.”

Robert Stoldal, a longtime television journalist and executive, is a member of The Mob Museum Board of Directors.

Feedback or questions? Email blog@themobmuseum.org